This video from Dr Rachel Maunder, Associate Professor in Psychology, provides some examples of active, blended learning approaches that Rachel has tried in her modules so far. Rachel shares two different models, one which focuses on linking classroom activity to independent study tasks online, and one which includes some teaching in the online environment in addition to face to face sessions. Rachel also shares useful lessons she has learned from her experiences so far.

If you have questions about either of these approaches, Rachel is happy to take these via email.

This post is one in a series of ABL Practitioner Stories, published in the countdown to Waterside. If you’d like us to feature your work, get in touch: LD@northampton.ac.uk

So argues Dr Chris Willmott, Senior Lecturer in Biochemistry at the University of Leicester.

In a recent article for Viewfinder, entitled Science on Screen, Dr Willmott discusses his use of clips from films and television programmes in his university bioscience teaching. Dr Willmott considers a number of ways in which clips from science programmes and popular films (even those which get the science woefully wrong) can be used as teaching aids, all of which are designed to promote engagement with the subject, and which can be incorporated into a flipped learning session.

He categorises his use of clips from films and television programmes in the following way, which you can read more about in his article:

- Clips for illustrating factual points

- Clips for scene setting

- Clips for discussion starting

Obviously not all science programmes get things right, but rather than being off-putting, this can be a great starter for a teaching and learning session. In the following example, Dr Willmott explains how he makes use of a clip in which Richard Hammond ‘proves’ that humans can smell fear:

Students are asked to watch the clip and keep an eye out for aspects of the experiment that are good, and those features that are less good. These observations are then collated, before the students are set the task of working with their neighbours to design a better study posing the same question.

If you’re interested in using visual content to aid the teaching of science then there are an increasing number of visual resources available. Dr Willmott mentions the Journal of Visualised Experiments in his article, a journal which is now in it’s tenth year, and which has over 4,000 peer-reviewed video entries. It’s a subscription only journal, and we don’t have a subscription, but if it looks good and you speak nicely to your faculty librarian then who knows what might be possible!

A resource that we do subscribe to is Box of Broadcasts, a repository of over a million films and television programmes. Accessible to academics and students (as long as they are in the UK), BoB programmes are easily searched, clipped, organised in playlists, and linked to from NILE. Plenty of material from all your science favourites such as Brian Cox, Iain Stewart and Jim Al-Khalili and even the odd episode from classic science documentaries like Cosmos and The Ascent of Man.

A free, and very high quality visual resource is the well known Periodic Table of Videos, created by Brady Haran and the chemistry staff at the University of Nottingham. Also of interest to chemists (but not free) are The Elements, The Elements in Action, and the Molecules apps developed by Theodore Grey and Touch Press. Known collectively as the Theodore Grey Collection, these iOS only apps may end up being the best apps on your iPad.

Not visual at all, but still very good, is the In Our Time Science Archive – hundreds of free to download audio podcasts from Melvyn Bragg and a wide range of guests on many, many different scientific subjects from Ada Lovelace to Absolute Zero.

by Robert Farmer and Paul Rice

It’s no easy thing to create an interesting, engaging and effective educational video. However, when developing educational presentations and videos there are some straightforward principles that you can apply which are likely to make them more effective.

The following videos were created for our course, Creating Effective Educational Videos, and will take you through the dos and dont’s of educational video-making.

1. How not to do it!

This short video offers a humorous take on how not to make great educational videos.

- Prof. Oliver Deer discusses his approach to making educational videos: https://youtu.be/cKXx9GkeGGQ

2. Understanding Mayer’s multimedia principles

This 20 minute video outlines Richard Mayer‘s principles of multimedia learning and provides practical examples of how these principles might be applied in practice to create more effective educational videos.

- A Practical Guide to Mayer’s Multimedia Principles: https://youtu.be/m0GMZgaC7gM

3. Applying Mayer’s mutimedia principles

Because much of Mayer’s work centres around STEM subjects (which typically make a lot of use of diagrams, charts, tables, equations, etc.) We spent some time thinking about how to apply his principles in subjects which are more text based. To this end, we recorded a 12 minute video lecture which is very on-screen text heavy in which we tried to make use of as many of Mayer’s principles as possible.

- Are we ever justified in silencing those with whom we disagree? https://youtu.be/Dyu94dH2aeo

4. Understanding what students want, and don’t want, from an educational video

Given the current popularity of educational videos, and given the time, effort and expense academics and institutions are investing to provide educational videos to students, we thought that it was worthwhile to evaluate whether students actually want and use these resources. You can find the results of our investigation in our paper:

- Rice, P. and Farmer, R. (2016) Educational videos – tell me what you want, what you really, really want. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, Issue 10, November 2016. Available from: https://journal.aldinhe.ac.uk/index.php/jldhe/article/view/297

5. Further reading

Mayer, R. (2009) Multimedia Learning, 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press.

https://www.cambridge.org/gb/academic/subjects/psychology/educational-psychology/multimedia-learning-2nd-edition

Rice, P., Beeson, P. and Blackmore-Wright, J. (2019) Evaluating the Impact of a Quiz Question within an Educational Video. TechTrends, Volume 63, pp.522–532.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-019-00374-6

Most university lecturers will have their favourite anti-lecturing quote. Mine has always been Camus’ oft-quoted “Some people talk in their sleep. Lecturers talk while other people sleep”. Another favourite is the variously attributed definition “Lecture: a process by which the notes of the professor become the notes of the student, without passing through the minds of either.”

In fairness to university lecturers, none of the lecturers I know deliver these kind of dreary monologues. Also, if a lecturer is timetabled into a room with a lectern, projector and screen, and tiered seating containing 250 students then surely we cannot chastise them for using that room for the purpose it was designed and intended for. Obviously such space can be subverted and used differently (as professors such as Eric Mazur and Simon Lancaster have done), but surely the best solution is simply not to build these kinds of spaces in the first place. If active, participatory learning in small groups is what is best (and the evidence suggests that it is) then why not build spaces that accommodate this kind of learning and teaching.

At the University of Northampton that’s exactly what is happening. As was recently reported in the Sunday Times, the University of Northampton’s Waterside campus “is to be built with no traditional lecture theatres, providing further evidence that the days of professors imparting knowledge to hundreds of students at once may be numbered.” The new campus “is the first in the UK to be designed without large auditoriums.”

While it is true that the majority of teaching that takes place at the Waterside campus is planned to be active, interactive and participatory, and to take place in small classes, there will obviously need to be some element of professors imparting knowledge to their students. This is, after all, for most people a key part of the process of teaching and learning. However, the plan for Waterside is for such ‘professorial knowledge imparting’ to take place online, prior to attending class; a process often known as flipped or blended learning. This means that time is not taken up in the small class sessions with getting knowledge across to the students, or with ‘covering content’, but on helping students to understand, assimilate and make sense of the knowledge they have grappled with prior to attending class.

Professor Nick Petford, Vice Chancellor of the University of Northampton, is not only building a campus in which active, participatory, small class teaching will be the norm, but as a member of the teaching staff he is already teaching in this way himself. Professor Petford adopted this blended learning approach in his physical volcanology classes during the 2015/16 academic year, and you can see him talking about how it went in this video.

Yes, they probably will. A recent study conducted at Queen’s University Belfast reported that students are more likely to view the availability of recorded lectures as a reinforcement of class teaching, rather than a replacement of it.

In a post-course survey, 96 per cent of students said that the availability of footage had had no impact on their attendance … [and] 98 per cent of students said that revision in preparation for an exam was a primary reason for viewing a video.

A brief summary of the research published in the THES is available here.

This is a fairly long blog post, so in case you don’t have time to read it all, the key message is this:

Flipping the classroom is likely to lead to improvements in student performance and reduced failure rates when it is used as part of an overall strategy to create a more active learning environment. These gains are likely to have the greatest impact in classes with less than fifty students.

"Education is not an affair of 'telling' and being told, but an active and constructive process." John Dewey, Democracy and Education, 1916

One important question arising from our earlier blog posts, ‘What is the flipped classroom?’ and, ‘Designing a flipped module in NILE’, is whether or not flipping your class will improve student learning. Clearly there must be some evidence to support a flipped approach to teaching and learning, otherwise we wouldn’t be suggesting it, but what is that evidence, and where is it?

At the risk of appearing to concede defeat before we’ve even begun, I would like to start by looking at a recent paper which argues that flipping the classroom does not guarantee any gains in student achievement.

Flipping the classroom is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition to generate improvements in learning

‘Improvements from a Flipped Classroom May Simply Be the Fruits of Active Learning’ is a very interesting paper by Jensen, et al (2015), and it is clear from the title what their findings are. They begin the paper by stating one of the main problems behind many of the claims that the flipped classroom improves student learning, which is that there are normally too many variables that have changed between the flipped and the non-flipped classroom to isolate flipping as the key variable. They note that flipping the classroom usually leads to more active learning taking place (indeed, this is often the reason that teachers want to flip the classroom in the first place), and they investigated the extent to which the increase in the amount of active learning, not flipping, is the key variable.

Jensen, et al (2015) took a class of 108 students and divided them into two groups, one of 53 and one of 55. One group had a flipped experience, the other a non-flipped experience – however, both sessions were very active. The diagram on the left indicates how the sessions worked. The flipped and non-flipped classes were compared with each other, and also with the previous year’s class of 94 students, referred to as the original class. While the content and the underlying structure of the teaching remained consistent, a great deal of time and effort was put into creating additional materials for the flipped and non-flipped classes, which is evident from reading the paper.

As will be clear from the title of the paper, the flipped classroom did not produce statistically significant learning gains or improvements in attitudes to learning over the non-flipped classroom, and neither the flipped nor the non-flipped classroom significantly outperformed the original class. The one area in which the flipped classroom did produce a statistically significant improvement was in final examination scores of low level items (e.g., remember and understand type questions) over the original class.

Regarding these results I think that it is important to make at least two observations. Firstly, it should be borne in mind that the students in the study were high ability, highly motivated students attending a private university at which the average ACT score of students is 28 and average GPA is 3.82. For context, an ACT score of 28 would put a student in the top 10% and a GPA of 3.82 would be between an A- and an A. Whilst not necessarily Oxbridge students, they are solid Russell Group students, the kind of students who “virtually teach themselves; they do not need much help from us” (Biggs and Tang, 2011, p.5). Secondly, the original class appears to have been be a fairly active class already, certainly if judged by the standards set in the definition by Freeman, et al (2014) which we will look at later.

The study by Jensen, et al., did come up with other interesting findings though. One finding (2015, p.8 and p.10) which reinforces the importance of time spent with lecturers was that,

Students “perceived their time with the instructor as more influential for learning, regardless of whether they were participating in” the flipped class or in the non-flipped class … “the presence of the instructor and/or peer interaction had a greater influence on students’ perceptions of learning than the activities themselves.”

Additionally, Jensen, et al., were not dismissive of the potentials and advantages of the flipped classroom, noting (2015, p.10) that,

“If active learning is not currently being used or is being used very rarely, the flipped classroom may be a viable way to facilitate the use of such approaches, if the costs of implementation are not too great. As the research indicates, using active learning in the flipped approach can increase student learning as well as student satisfaction over traditional, non-active learning approaches.”

The claim made by Jensen, et al., that active learning is the key variable is certainly very credible, and, as we shall see, it is increasingly apparent in recent publications that flipping the classroom is a very popular way of creating a more active learning environment.

Flipping the classroom is a good way of making classrooms more active

‘The Flipped Classroom of Operations Management: A Not-For-Cost-Reduction Platform’ is a 2015 paper by Asef-Vaziri, and it provides an excellent introduction to the flipped classroom. Additionally, the literature review in the paper gives a good overview of some recent publications on the subject. A wide variety of active learning ideas are discussed in the paper (pp.74-80) and they give a good insight into the practical workings of Asef-Vaziri’s flipped classroom. Right from the outset Asef-Vaziri (2015, p.72) makes it clear that the benefits of using the flipped classroom are because it allows more class time to be spent engaged in active learning:

“Class time is no longer spent teaching basic concepts, but rather on more value-added activities, such as problem solving, answering questions, systems thinking, and potentially on collaborative exercises such as case studies, Web based simulation games, and real-world applications”

Asef-Vaziri’s classes were fully flipped in the autumn of 2012 (141 students) and 2013 (157 students), and the average grades were compared to those of the classes in the spring and autumn of 2011 (both with 160 students) which not flipped. The results were as follows:

| Autumn 2012 flipped classroom |

Autumn 2013 flipped classroom |

|

| Average grade increase over spring 2011 traditionally taught class |

+7.4% | +7.3% |

| Average grade increase over autumn 2011 traditionally taught class |

+11.8% | +11.6% |

The improvements in Asef-Vaziri’s students’ grades are undoubtedly impressive, and these high gains are likely to result from the significant amount of time and effort that Asef-Vaziri put into re-designing the course.

What came across very clearly in Asef-Vaziri’s paper is the idea that the flipped classroom offers ‘the best of both worlds’, creating increased opportunity to engage in active learning in ways that are difficult for the traditional classroom (due to lack of time) and difficult for online classes (due to lack of face-to-face interactions).

A cursory glance at a number of other recent publications about the flipped classroom makes it clear that a key motivation for using it has been in order to create more active learning opportunities. For example, in their paper, ‘Moving from Flipcharts to the Flipped Classroom: Using Technology Driven Teaching Methods to Promote Active Learning in Foundation and Advanced Masters Social Work Courses’, Holmes, et al (2015) state that the desire to engage in more active learning was the primary driver behind introducing the flipped classroom.

A number of other papers bear out the notion that flipping the classroom is a popular way of adopting a more active approach to teaching and learning, including: Gilboy, et al (2014); Hung (2015); Love, et al (2013); Roach (2104); See and Conry (2014); Simpson and Richards (2015); and Tune, et al (2013). All of these papers make the connection between the flipped classroom and increasingly active approaches to teaching and learning.

Hopefully the above discussion goes some way to making the case that the flipped classroom is a good (or, at least, a popular) way of creating a more active classroom. We will now look at some more evidence in support of the idea that adopting an active approach to teaching and learning is likely to improve student performance.

Active learning increases student performance

Active learning is certainly not a new idea. John Dewey (1902, p.6) knew that learning is an active process, and referred to it as such since the beginning of the last century. Some years later, 112 to be exact, Freeman, et al (2014) published an important meta-analysis of STEM education in which 158 active learning classes were compared with 67 traditionally taught classes. Aleszu Bajak, writing in the daily news site of the journal ‘Science’, summarised the paper as follows: ‘Lectures Aren’t Just Boring, They’re Ineffective, Too, Study Finds’. And Eric Mazur, cited in Bajak (2014), said

“This is a really important article—the impression I get is that it’s almost unethical to be lecturing if you have this data.”

The results of the paper “indicate that average examination scores improved by about 6% in active learning sections, and that students in classes with traditional lecturing were 1.5 times more likely to fail than were students in classes with active learning.” (Freeman, et al, 2014, p.8410) To get a sense of the significance of the results, the authors note (p.8413) that had it been a medical randomised control trial it may have been stopped early because of the clear benefit of the intervention being tested; in this case, the active learning. The authors also note that because the retention of students on active learning courses is higher, and because it is lower ability learners who typically drop-out, the positive effects of active learning could actually be greater than reported because the active learning classes were holding on to a higher proportion of their lower ability learners than the traditional classes. And, good news for Waterside, active learning was shown to have “the highest impact on courses with 50 or fewer students.” (p.8411)

One issue which may be useful is to define what is meant by active learning. For the purposes of their study, Freeman, et al (2014, p.8413-4) adopted the following definition:

“Active learning engages students in the process of learning through activities and/or discussion in class, as opposed to passively listening to an expert. It emphasises higher-order thinking and often involves group work.”

Freeman, et al (2014, p.8410) state that for the purposes of their study the “active learning interventions varied widely in intensity and implementation, and included approaches as diverse as occasional group problem-solving, worksheets or tutorials completed during class, use of personal response systems [clickers] with or without peer instruction, and studio or workshop course designs.”

Other studies about the effectiveness of adopting a more active approach to teaching and learning in STEM subjects include Hake’s 1998 paper ‘Interactive-engagement vs traditional methods: A six-thousand student survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics courses.’ The paper concludes that:

“Comparison of IE [interactive engagement] and traditional courses implies that IE methods enhance problem-solving ability. The conceptual and problem-solving test results strongly suggest that the use of IE strategies can increase mechanics-course effectiveness well beyond that obtained with traditional methods.”

Also of interest is ‘Peer Instruction: Ten years of experience and results’ in which Crouch and Mazur (2001) discuss the positive effects of replacing a more traditional approach to physics teaching with Mazur’s method of peer instruction, an approach to teaching and learning developed in the 1990s which inspired the flipped classroom movement.

Whilst a good deal of the most rigorous and credible quantitative studies into active learning have been carried out in STEM subjects, Hung (2015) makes the point in the paper ‘Flipping the classroom for English language learners to foster active learning’, that,

“it is evident that although the flipped classroom approach has mainly been conducted in STEM fields, its feasibility across disciplines (in this case, language education) should not be underestimated.”

Conclusion

It’s important to make clear that this has not been an extensive, rigorous and systematic study of every recent publication on the flipped classroom, so any conclusions drawn must take that into account. Nevertheless, and with this in mind, I think that we can still draw a few conclusions with certainty, and a few more with slightly less certainty.

We can be very confident that:

- Active learning produces statistically significant improvements in student achievement in science, engineering and mathematics.

- Active learning in classrooms of under 50 students produces the largest gains.

- Even a small amount of active learning will produce positive gains in student achievement.

We can be reasonably confident that:

- The positive effects of active learning seen in science, engineering and mathematics will be applicable to other subject areas.

- Lecturers in a variety of subject areas have successfully flipped their classrooms.

- The gains in students’ learning achieved by the flipped classroom are more likely to be a result of increasing the amount of active learning taking place online and/or in the classroom.

- Flipping the classroom is a good way of creating a more active learning environment.

It may be the case that:

- The gains in student achievement produced by flipping the classroom will have a greater effect in non-Russell Group universities.

- Flipping the classroom will have a greater effect when focused at the level of knowledge, understanding and application rather than analysis, synthesis and evaluation.

From the papers looked at, it is not clear:

- Whether there are significant differences in the effectiveness of different types of flipped/active learning opportunities.

- Whether there is an optimal level of student activity online and in the classroom (i.e., is more always better?)

- Whether students from all cultural backgrounds experience similar improvements in performance from the flipped/active classroom.

- Whether students whose first language is not the language in which the course is taught experience additional benefits or disbenefits from flipped/active classroom.

Readers wanting to look at the literature themselves and draw their own conclusions are directed to the further reading section at the end of this blog post, which provides links to many recent papers on the flipped classroom from a diverse range of subject areas.

References

Asef-Vaziri, A. (2015) The Flipped Classroom of Operations: A Not-For-Cost-Reduction Platform. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education. 13(1), pp.71-89.

Bajak, A. (2014) ‘Lectures Aren’t Just Boring, They’re Ineffective, Too, Study Finds’ Science News. 12th May.

Biggs, J. and Tang, C. (2011) Teaching for Quality Learning at University, 4th Edition. Berkshire: Open University Press.

Dewey, J. (1902) The Child and the Curriculum. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p.9.

Crouch, C. and Mazur, E. (2001) Peer Instruction: Ten years of experience and results. American Journal of Physics. 69(9), pp.970-977.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S., McDonough, M., Smith, M., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H. and Wenderoth, M. (2014) Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering and mathematics. PNAS. 111(23), pp.8410-8415.

Gilboy, M., Heinerichs, S. and Pazzaglia, G. (2015) Enhancing Student Engagement Using the Flipped Classroom. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 47(1), pp.109-114.

Hake, R. (1998) Interactive-engagement versus traditional methods: A six-thousand-student survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics courses. American Journal of Physics. 66(1), pp.64-74.

Holmes, M., Tracey, E., Painter, L., Oestreich, T. and Park, H. (2015) Moving from Flipcharts to the Flipped Classroom: Using Technology Driven Teaching Methods to Promote Active Learning in Foundation and Advanced Masters Social Work Courses. Clinical Social Work Journal.43(2), pp.215-224.

Hung, H-T. (2015) Flipping the classroom for English language learners to foster active learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning. 28(1), pp.81-96.

Jensen, J., Kummer, T.. and Godoy, P. (2015) Improvements from a Flipped Classroom May Simply Be the Fruits of Active Learning. CBE – Life Sciences Education. 14(1), pp.1-12.

Love, B., Hodge, A., Grandgenett, N. and Swift, A. (2014) Student learning and perceptions in a flipped linear algebra course. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology. 45(3), pp.317-324.

Roach, T (2014) Student perceptions toward flipped learning: New methods to increase interaction and active learning in economics. International Review of Economics Education. 17, pp.74-84.

See, S. and Conry, J. (2014) Flip My Class! A faculty development demonstration of a flipped-classroom. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. 6(4), pp.585-588.

Simpson, V. and Richards, E. (2015) Flipping the classroom to teach population health: Increasing the relevance. Nurse Education in Practice.15(3), pp.162-167.

Tune, J., Sturek, M. and Basile, D. (2013) Flipped classroom model improves graduate student performance in cardiovascular, respiratory, and renal physiology. Advances in Physiology Education. 37(4), pp.316-320.

Further reading about the flipped classroom

Asef-Vaziri, A. (2015) The Flipped Classroom of Operations: A Not-For-Cost-Reduction Platform. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education. 13(1), pp.71-89.

Bristol, T. (2014) Flipping the Classroom. Teaching and Learning in Nursing. 9(1), pp.43-46.

Brunsell, E. and Horejsi, M. (2013) A Flipped Classroom in Action. The Science Teacher. 80(2), p.8.

Chen, Y., Wang. Y., Kinshuk, and Chen, N-S. (2014) Is FLIP enough? Or should we use the FLIPPED model instead? Computers & Education. 79, pp.16-27.

Enfield, J. (2013) Looking at the Impact of the Flipped Classroom Model of Instruction on Undergraduate Multimedia Students at CSUN. TechTrends. 57(6), pp.14-27.

Forsey, M., Low, M. and Glance, D. (2013) Flipping the sociology classroom: Towards a practice of online pedagogy. Journal of Sociology. 49(4), pp.471-485.

Gilboy, M., Heinerichs, S. and Pazzaglia, G. (2015) Enhancing Student Engagement Using the Flipped Classroom. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 47(1), pp.109-114.

Herreid, C. amd Schiller, N. (2013) Case Studies and the Flipped Classroom. Journal of College Science Teaching. 42(5), pp.62-66

Holmes, M., Tracey, E., Painter, L., Oestreich, T. and Park, H. (2015) Moving from Flipcharts to the Flipped Classroom: Using Technology Driven Teaching Methods to Promote Active Learning in Foundation and Advanced Masters Social Work Courses. Clinical Social Work Journal. 43(2), pp.215-224.

Hung, H-T. (2015) Flipping the classroom for English language learners to foster active learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning. 28(1), pp.81-96.

Jacot, M., Noren, J. and Berge, Z. (2014) The Flipped Classroom in Training and Development: Fad or the Future? Performance Improvement. 53(9), pp.23-28.

Jensen, J., Kummer, T.. and Godoy, P. (2015) Improvements from a Flipped Classroom May Simply Be the Fruits of Active Learning. CBE – Life Sciences Education. 14(1), pp.1-12.

Kim, M., Kim, S., Khera, O. and Getman, J. (2014) The experience of three flipped classrooms in an urban university: an exploration of design principles. The Internet and Higher Education. 22, pp.37-50.

Love, B., Hodge, A., Grandgenett, N. and Swift, A. (2014) Student learning and perceptions in a flipped linear algebra course. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology. 45(3), pp.317-324.

Lujan, H. and DiCarlo, S. (2014) The flipped exam: creating an environment in which students discover for themselves the concepts and principles we want them to learn. Advances in Physiology Education. 38(4), pp.339-342.

Roach, T (2014) Student perceptions toward flipped learning: New methods to increase interaction and active learning in economics. International Review of Economics Education. 17, pp.74-84.

See, S. and Conry, J. (2014) Flip My Class! A faculty development demonstration of a flipped-classroom. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. 6(4), pp.585-588.

Simpson, V. and Richards, E. (2015) Flipping the classroom to teach population health: Increasing the relevance. Nurse Education in Practice. 15(3), pp.162-167.

Slomanson, W. (2014) Blended Learning: A Flipped Classroom Experiment. Journal of Legal Education. 64(1), pp.93-102.

Tune, J., Sturek, M. and Basile, D. (2013) Flipped classroom model improves graduate student performance in cardiovascular, respiratory, and renal physiology. Advances in Physiology Education. 37(4), pp.316-320.

Having redesigned her Leading Public Health Practice module from being fully face-to-face, to blended, Sue Everett in the School of Health, reflects on the skills she developed in the process and how she has moved from being a ‘technophobe’ to the ‘go to’ girl for technology in her office!

Having redesigned her Leading Public Health Practice module from being fully face-to-face, to blended, Sue Everett in the School of Health, reflects on the skills she developed in the process and how she has moved from being a ‘technophobe’ to the ‘go to’ girl for technology in her office!

If you have any questions about CAIeRO, or would like to book one for your module team, please email LD@northampton.ac.uk. If you would like to talk further to Sue about her experiences, she is happy for you to contact her.

In March/April 2014, Sue Everett, Kirsty Mason and Stuart Allen in the School of Helath underwent a CAIeRO on their three modules for the PGC in Public Health. Initially redesigned for fully online learning, the Programme was slightly altered to reintroduce some face-to-face sessions, resulting in a ‘Waterside-ready’, set of blended learning modules.

In March/April 2014, Sue Everett, Kirsty Mason and Stuart Allen in the School of Helath underwent a CAIeRO on their three modules for the PGC in Public Health. Initially redesigned for fully online learning, the Programme was slightly altered to reintroduce some face-to-face sessions, resulting in a ‘Waterside-ready’, set of blended learning modules.

Having run her module in the new design, Sue shares some of her reflections on the process and her learning experiences in this video.

If you have any questions about CAIeRO, or would like to book one for your module team, please email LD@northampton.ac.uk. If you would like to talk further to Sue about her experiences, she is happy for you to contact her.

Q: How do you eat an elephant?

A: One bite at a time!

The move to Waterside can seem as if it isn’t really that long away, given all that you may feel you have to do inbetween now and then. Wondering where to start can also seem daunting and the mountain of work that you see ahead of you can be so huge that you can’t even see the summit, let alone work out a route to the top.

The move to Waterside can seem as if it isn’t really that long away, given all that you may feel you have to do inbetween now and then. Wondering where to start can also seem daunting and the mountain of work that you see ahead of you can be so huge that you can’t even see the summit, let alone work out a route to the top.

In supporting staff to get to grips with the course redesign implications that are predicated on a number of guiding principles about how learning and teaching will look, the Learning Design team came across a really useful set of blog posts by Tony Bates, a Canadian Research Associate who is also President and CEO of Tony Bates Associates Ltd and who, according to their website are “a private company specializing in consultancy and training in the planning and management of e-learning and distance education.”

The blog posts were written to help people understand and implement a series of practical steps to help deliver quality in their online learning materials. While I don’t wish to duplicate the posts here, I thought it might be helpful to summarise some of the key points in an attempt to help you to start thinking about how you might begin to eat your own elephant, or climb that mountain. I found some obvious points in the posts, some practical and straightforward suggestions and some real gems. There are also some questions and exercises to get you started along the road to redesigning your own modules.

I should also preface this post with the reminders that, as an institution, we are definitely NOT going fully online but will be exploring ways to enhance our learning and teaching using technology and that the precise nature of each blended module is for staff teams to determine.

The Nine Steps are as follows (each link will take you straight to the original post)

- Step 1: Decide how you want to teach online

- Step 2: Decide on what kind of online course

- Step 3: Work in a Team

- Step 4: Build on existing resources

- Step 5: Master the technology

- Step 6: Set appropriate learning goals

- Step 7: Design course structure and learning activities

- Step 8: Communicate, communicate, communicate

- Step 9: Evaluate and innovate

Step 1: Decide how you want to teach online

This step highlights the importance of rethinking the way you teach when you go online and redesigning the teaching to meet the needs of your online learners given that their needs may differ because of the specific learning context. The gem in this post is the emphasis on asking you to consider your basic teaching philosophy – what is your role and how would you like to tackle some of the limitations of classroom teaching and renew your overall approach to teaching? As Bates himself says: “It may not mean doing everything online, but focussing the campus experience on what can only be done on campus.”

This step highlights the importance of rethinking the way you teach when you go online and redesigning the teaching to meet the needs of your online learners given that their needs may differ because of the specific learning context. The gem in this post is the emphasis on asking you to consider your basic teaching philosophy – what is your role and how would you like to tackle some of the limitations of classroom teaching and renew your overall approach to teaching? As Bates himself says: “It may not mean doing everything online, but focussing the campus experience on what can only be done on campus.”

Step 2: Decide on what kind of online course

Bates describes a continuum of online learning ranging from online classroom aids to fully online and explores four key factors that will influence the kind of online course you should be teaching:

Bates describes a continuum of online learning ranging from online classroom aids to fully online and explores four key factors that will influence the kind of online course you should be teaching:

- your teaching philosophy (see step 1)

- the kind of students you are trying to reach (or will have to teach)

- the requirements of the subject discipline

- the resources available to you

A number of subject groups and disciplines are already starting to explore what the current direction of travel for learning and teaching at Northampton might look like for them and developing models and suggestions for how to redesign their modules and programmes within a broader set of principles. It is useful to note that while Bates experience suggests that “almost anything can be effectively taught online, given enough time and money” (emphasis added), the reality is that resources are finite and that it is therefore imperative to work out what could and should be taught face-to-face and what could and should be taught online, remembering that we are still going to be primarily a campus-based institution. He begins the process by differentiating between the teaching of content and the teaching or development of skills and provides a useful example of how this might look in practice.

The gem here is his consideration of how to make best use of the various resources available to you including time (the most precious resource of all), your learning technology support staff (always glad to help), your VLE (NILE) and your colleagues.

Step 3: Work in a Team

Online learning is different to classroom teaching and as a result will require staff to learn some new skills. You are unlikely to have all your F2F learning materials in a suitable format for online learning. This post considers how the team of staff around you can help you to move from where you are, to where you want to get to given that “particular attention has to be paid to providing appropriate online activities for students, and to structuring content in ways that facilitate learning in an asynchronous online environment”. Working in a team can also, of course, help with managing the workload, and with getting quickly to a high quality online standard, as well as being a way to save some of your time.

Online learning is different to classroom teaching and as a result will require staff to learn some new skills. You are unlikely to have all your F2F learning materials in a suitable format for online learning. This post considers how the team of staff around you can help you to move from where you are, to where you want to get to given that “particular attention has to be paid to providing appropriate online activities for students, and to structuring content in ways that facilitate learning in an asynchronous online environment”. Working in a team can also, of course, help with managing the workload, and with getting quickly to a high quality online standard, as well as being a way to save some of your time.

Step 4: Build on Existing Resources

As one Deputy Dean said at a recent School Learning and Teaching Development Day: “Let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater!”

This can include repurposing your own content, but also drawing on existing online resources (TED talks, The Khan Academy, iTunesU) as well as ‘raw’ content that you can use as the basis for developing learning activities and he argues that ‘only in the areas where you have unique, original research that is not yet published, or where you have your own ‘spin’ on content, is it really necessary to create ‘content’ from scratch”.

The hidden gem? Distinguishing between using existing resources that “do not transfer well to an online learning environment (such as a 50 minute recorded lecture), and using materials already specifically developed for online teaching”. He suggests that you “take the time to be properly training in how to use [NILE]”, recognising that a 2-hour investment now can save you hours of time later on.

Step 5: Master the Technology

That’s it really – come to some training on the tools that you would like to use and know more about! This includes learning about their strengths and weaknesses so that you know that you have selected the right tool for the job, but also have a clearer idea about how they might work in practice or how to avoid some of the pitfalls. There are plenty of tools out there, but selecting the right tool is an instructional or pedagogical issue that requires you to be clear on what it is that you are trying to achieve.

Bates’ gem (from my perspective) is his no-nonsense approach to engaging with central training and development initiatives. Here are a few that might help:

- The CLEO (Collaborative Learning Experiences Online) workshop that forms part of our C@N-DO staff development programme is a good way of putting yourself in the shoes of the online learning and experiencing first hand some of the obstacles that online learners face, in order to prevent your own students facing similar issues.

- NILE training (around specific pedagogical purposes) is provided by the Learning Technology team and in addition to regular scheduled training, can also be tailored to suit the purposes of your subject team or discipline. Please just ask!

- Spend a little time each year looking at any of the new features added to NILE during the year (Check out the Learntech Blog for updates).

Finally in this step is a discussion around why simply recording your lectures is not the best way to go. Definitely worth the time to read through his reasons, if this is something you were considering.

Step 6: Set appropriate Learning Goals

In short, should the learning goals (outcomes) for online/blended learning be the same as, or different to the same module delivered in a fully face-to-face mode? The key differentiator is that while the goals may well remain the same, the method may change. He also raises the question as to whether additional learning outcomes need to be considered in terms of the development of 21st century learning skills (in particular, learning the skills to ‘manage knowledge’ long after they graduate).

In short, should the learning goals (outcomes) for online/blended learning be the same as, or different to the same module delivered in a fully face-to-face mode? The key differentiator is that while the goals may well remain the same, the method may change. He also raises the question as to whether additional learning outcomes need to be considered in terms of the development of 21st century learning skills (in particular, learning the skills to ‘manage knowledge’ long after they graduate).

The link between learning outcomes and assessment is also explored here as is the way in which assessment drives student behaviour. He concludes by saying that “[b]ecause the internet is such a large force in our lives, we need to be sure that we are making the most of its potential in our teaching, even if that means changing somewhat what and how we teach”.

Step 7: Design Course Structure and Learning Activities

After an initial exploration between ‘strong’ and ‘loose’ online learning structures, Bates identifies the three main determinates of teaching structure as being:

- the organisational requirements of the institution;

- the preferred philosophy of teaching of the instructor; and

- the instructor’s perception of the needs of the students.

In the light of recent discussions here around what is meant by ‘contact’ hours (see this Definitions paper produced recently by the University’s Institute of Learning and Teaching), he identifies problems with this approach whilst simultaneously recognising that this is, nevertheless, the standard measuring unit for face-to-face teaching. One reason he highlights in particular is that it measures input, not output. Bates is also keen to ensure parity between online and face-to-face learning in terms of ensuring quality at Validation.

He discusses the time input as well as the structure of modules and how existing face-to-face structures mean we can already be some way down the path on module design, with the important proviso that it is important to ensure that content moved online is suitable for online learning. This is where the Learning Design team can help you to make decisions around what to teach or what to leave out, given that making some work optional means it should not be assessed and that if it is not assessed, students will quickly learn to avoid doing it.

This step concludes with a look at how to design student activities. This is typically something that would be covered during the second day of a CAIeRO curriculum redesign workshop, but anyone who has participated in any part of the C@N-DO programme will already have come into contact with some of these online learning activities / e-tivities. Some good points for consideration here though.

Step 8: Communicate, communicate, communicate

This steps explores the vital importance of ongoing, continuing communication between the tutor and the online learners, that is more than simply seeing them in class on a weekly basis. Maintaining tutor presence in the online environment is a “critical factor for online student success and satisfaction”, helping students recognise that their online contributions are just as much a part of their learning experience as the face-to-face components.

This steps explores the vital importance of ongoing, continuing communication between the tutor and the online learners, that is more than simply seeing them in class on a weekly basis. Maintaining tutor presence in the online environment is a “critical factor for online student success and satisfaction”, helping students recognise that their online contributions are just as much a part of their learning experience as the face-to-face components.

Creating a compelling online learning environment is possible but requires deliberate planning and conscientious design. It must also be done in such a way as to control the instructor’s workload. Bates has a number of ‘top tips’ for setting and managing student expectations online and emphasises that tutors should also adhere to these themselves. Like in the CLEO, he suggests starting with a small task in the first week that enables the guidelines to be applied, with the tutor paying particular attention to this activity. As he rightly points out …

students who do not respond to set activities in the first week are at high risk of non-completion. I always follow up with a phone call or e-mail to non-respondents in this first week, and ensure that each student is following the guidelines … What I’m doing is making my presence felt. Students know that I am following what they do from the outset.

There is a discussion here around the benefits and disadvantages of both synchronous and asynchronous communication – the decision again being based on pedagogical need. There is also a list of tips for how to manage online discussions for you to read an inwardly digest 🙂 and a consideration of how cultural factors can impact on participation.

Step 9: Evaluate and Innovate

We ask our students to do it all the time – let’s make sure we apply the same principles to our own learning and teaching development and complete our own reflective cycle. Bates has a series of questions to guide any evaluation of teaching (not just online teaching), linking it back to Step 1 where he defines what we mean in terms of ‘quality’ in online learning. This doesn’t have to be a hugely onerous task – we already have ways of answering some of the questions (e.g. student grades, student participation rates in online activities (track number of views), assignments, Evasys questionnaires etc).

We ask our students to do it all the time – let’s make sure we apply the same principles to our own learning and teaching development and complete our own reflective cycle. Bates has a series of questions to guide any evaluation of teaching (not just online teaching), linking it back to Step 1 where he defines what we mean in terms of ‘quality’ in online learning. This doesn’t have to be a hugely onerous task – we already have ways of answering some of the questions (e.g. student grades, student participation rates in online activities (track number of views), assignments, Evasys questionnaires etc).

Then consider what it is that you need to do differently next time, in this ongoing, iterative process of Quality Enhancement.

Hopefully you will have the opportunity to explore some of these blog postings as you begin to think about how to get ready for Waterside, even if you don’t agree with everything that Bates says!

Following on from the blog post, ‘What is the flipped classroom?’, it seemed that it would be useful to put the ideas discussed there into practice, and to design and build a flipped module in NILE. As you would expect, there is no one way of putting together a flipped module that will work well for everybody – how you choose to design and run your flipped course will depend on a number of things, such as the level of study, size of class, what you enjoy doing in your face-to-face sessions, and what it is that you’re teaching. How you design your course will also depend on what kind of blend you want between the online and the face-to-face teaching elements. For example, if you want to take a two hour a week face-to-face course, and put 50% of the teaching online, this could be blended as a one hour online and one hour face-to-face session every week. However, it could also be done as a two hour online session in week one, followed by a two hour face-to-face session in week two, and so on. You could also rotate the online and face-to-face sessions on a three or four (or more) week basis, or even have all of term one online, and all of term two face-to-face (or vice versa).

The (fictional) course that has been designed and built in NILE has been created with the following in mind:

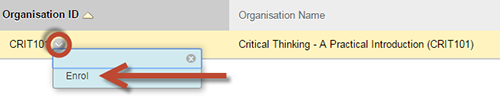

Title of module: CRIT101: Critical Thinking – A Practical Introduction

Level: 4

Credits: 10

Duration of course: 12 weeks

Contact hours per week: 2

Blend: 50%

Blend type: weekly blend (1 hour online, 1 hour face-to-face per week)

Additionally, the course has been built with the aim that the face-to-face sessions should be highly participatory and focussed as much as possible on dialogue with and between students. Again, this is not necessarily how everyone will want to run their face-to-face sessions – you may prefer to do just in time teaching1, peer instruction2, team-based learning3, problem-based learning4, small-group teaching5, or any number and mixture of other things that you can do in a face-to-face teaching space.

If you would like to find out more, you can enrol yourself on ‘Critical Thinking – A Practical Introduction’ and browse through the materials and the activities. The course begins with a set of three Panopto presentations which introduce the course and the NILE site to students, so this is a good place to begin when looking through the course. To access the course, login to NILE and click on the ‘Sites and Organisations’ tab. Type ‘CRIT101’ in the ‘Organisation Search’ box, and click ‘Go’. You will then see the course listed in the search results. Click on the drop-down menu next to CRIT101, and select enrol (see screenshot below).

The course is fully functional, so feel free to contribute to the discussion boards and take the tests, etc. It’s also very mobile friendly, so works well via the iNorthampton app on iOS and Android devices.

If you have any thoughts on the course, suggestions for improvements, etc., please feel free to respond to this blog post, or to email me directly at robert.farmer@northampton.ac.uk. If you would like to arrange a meeting with a learning designer to discuss what technologies are available in NILE and how you could further develop your own modules, please email LD@northampton.ac.uk.

Notes

1. Just in Time Teaching (JiTT) is a responsive method of teaching in which the content of the in-class sessions is determined by student responses to online activities, often only completed between 1 and 24 hours before the class begins. For more information see: http://www.edutopia.org/blog/just-in-time-teaching-gregor-novak

2. Peer instruction is a method of teaching developed by Eric Mazur at Harvard University in the 1990s. For more information, a good place to start is: http://blog.peerinstruction.net/2013/08/26/the-6-most-common-questions-about-using-peer-instruction-answered/

3. Team-Based Learning (TBL) is an approach to teaching and learning developed by Larry Michaelsen. For more information see: http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/team-based-learning/

4. For more information about Problem-based Learning (PBL) (and enquiry-based and action learning) see: http://www.learningandteaching.info/teaching/pbl.htm

5. A useful guide to small group teaching can be found in Phil Race’s book, ‘The Lecturer’s Toolkit, 4th Edition’ (Routledge, 2015). See, chapter 4 ‘Making small-group teaching work’.

Recent Posts

- 15 Years of the Learning Technology Blog!

- Blackboard Upgrade – March 2026

- Blackboard Upgrade – February 2026

- Blackboard Upgrade – January 2026

- Spotlight on Excellence: Bringing AI Conversations into Management Learning

- Blackboard Upgrade – December 2025

- Preparing for your Physiotherapy Apprenticeship Programme (PREP-PAP) by Fiona Barrett and Anna Smith

- Blackboard Upgrade – November 2025

- Fix Your Content Day 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – October 2025

Tags

ABL Practitioner Stories Academic Skills Accessibility Active Blended Learning (ABL) ADE AI Artificial Intelligence Assessment Design Assessment Tools Blackboard Blackboard Learn Blackboard Upgrade Blended Learning Blogs CAIeRO Collaborate Collaboration Distance Learning Feedback FHES Flipped Learning iNorthampton iPad Kaltura Learner Experience MALT Mobile Newsletter NILE NILE Ultra Outside the box Panopto Presentations Quality Reflection SHED Submitting and Grading Electronically (SaGE) Turnitin Ultra Ultra Upgrade Update Updates Video Waterside XerteArchives

Site Admin