transparent

Pronunciation /trænˈspær.ənt/

1 see through

2 obvious; clear and easy to understand or recognize

3 open and honest, without secrets

Cambridge dictionary 2019

Transparent pedagogy is partly about making your intentions (your learning design) clear to the students. It’s partly about helping them to understand what to expect from you, and what is expected of them. It can be a great way of establishing responsibilities and partnership in the learning environment, and circumventing passive ‘consumer-style’ approaches to learning. But it’s also about developing metacognition, helping students think about how learning works, and how knowledge is constructed. Below are some examples that I think illustrate this approach really well.

This publicly-available Digital Sociology Syllabus by Prof Tressie McMillan Cottom is a great example, as it outlines the rationale behind her pedagogic choices, and openly prepares her students for the challenges of the chosen approach. I love how frankly she describes the requirements to her students – my favourite bit is this:

“Throughout the course, I expect you to engage each other’s work and the assigned reading substantively. We do not do that “leave a comment on a thread every week by five where you just write two sentences for a grade” nonsense in this course. This is not an independent study class with me or a MOOC. You should learn from each other as much, if not more than you learn from me.”

The syllabus is for an online course, which arguably makes clarity all the more important, but the idea can be applied across the board – in face to face and blended teaching.

Transparent pedagogy is also about exposing the process of learning, focusing on the journey rather than the ‘end goal’ and making it clear when and how learning is happening as the course progresses. The idea of palimpsests is used by Amy Collier to illustrate this process; I particularly like this part:

“Palimpsest can frame how we think about student learning–that it accrues and traces on individual students’ histories and humanities–what they already bring to the educational environment. We can recognize that students will build and connect learning across the time they engage with us and with our institutions. That’s why portfolios projects that focus solely on creating final products (something that can be shown to an employer) miss the point. Palimpsest in student portfolios would allow students’ previous work and thinking to color the “final product.””

This metaphor emphasises two key ideas for me. First, transparent pedagogy is about dialogue, not just a set of instructions or a brief. You can’t make a student learn in a particular way just by explaining your intention, but you can help them see how it’s intended to work, and give them the language to analyse it. They will bring their own understanding to what you are offering and combine these to create something new.

The second point is that it’s honest. Learning is messy, uncomfortable, and rarely linear. This article by Jake Wright makes a case for transparent pedagogy as an effective response to “naive skepticism” from new students, which he claims can derive from a number of sources including distress at the disturbance of a previously held world view. He describes his approach as “metadisciplinary discussion” which should be meaningful, accessible and reinforced throughout the course. Wright argues that this approach can help students in introductory courses move past simplistic views about right and wrong answers and handle multiple interpretations – not by confrontation, but by encouraging them to practice “thinking like a disciplinarian”.

Finally, transparent pedagogy is also really beneficial when it comes to sharing teaching experience. Whether for peer observation, team teaching or handing over a course to a new member of staff or partner, having an explicit and detailed explanation of the thinking behind the construction can make all the difference in terms of delivery and student experience.

If you’d like to get some ideas on how to try this, get in touch with the Learning Design team. Or alternatively, if you’re already doing this, let us know how it’s going! We’d love to know if it’s making a difference for you and your students.

Active learning approaches are great for getting new perspectives, sharing ideas, co-creating knowledge and trying out new skills. Many of the recommended techniques for active learning in the classroom focus on encouraging participation and discussion; after all, the seminar model is a familiar one, and verbal contribution is a good way to gauge understanding and to generate a ‘buzz’ in the classroom. Right?

Right, but… (there’s always a ‘but’). As we at UoN continue to explore active pedagogies, and with an eye on inclusion and our upcoming Learning and Teaching Conference, I want to share some conversations I’ve had in the past few weeks that turn a critical eye on classroom discussion models and unpack them from an inclusion perspective.

What is ‘participation’ for, and what does it look like?

The first of these was a conversation with Lee-Ann Sequeira, Academic Developer in the Teaching and Learning Centre at LSE. It was inspired by her session at the recent Radical Pedagogies conference, and also by her thought-provoking blog post examining common perceptions of silent students in the classroom. I won’t repeat the content of that post here (though I definitely recommend reading it), but I wanted to pull out some points from the discussion that followed, which might be of interest if you’re experimenting with active learning approaches.

In some subjects, oral debate is a disciplinary norm, if not an employability requirement: those studying Law, Politics, Philosophy and so on can expect to spend considerable time developing these skills. In these and many other subjects though, debate or discussion is also used to support the learning process, and sometimes as a way to check whether students have prepared for the class. So when asking your students to contribute, it can be helpful to think about what you want to achieve, and how your learning goals should inform the format of that contribution. For example, when one of your goals is to help students develop the skills to effectively present their ideas to an audience, you might need to ensure that every student has an opportunity to do this, but when your goal is to explore and develop an idea from a range of perspectives, is it still necessary that every single student speaks? Aligning the structure of the activity to your goals or learning outcomes can help students understand what’s expected and focus their effort accordingly.

Quality not quantity

As Sequeira’s blog post observes, the literature on active learning focuses a lot on “how to draw [students] out of their shells” (Sequeira 2017). In addition to this, a quick Google search on “active learning” will reveal a myriad of magazine-style opinion pieces on the subject, many of which seem to be in danger of advocating verbal contribution almost for its own sake, and effectively conflating speaking with learning. How then to ensure that when using these approaches, our active classroom doesn’t become hostage to those who talk most, or echo chambers of students that feel they need to be seen to be ‘participating’?

One way to prevent this is by clearly establishing, and then building towards, high standards for individual contributions. When planning your session, think about what you’d like the end result to look like, and what contributions might be needed to get there – always bearing in mind of course that you are just one perspective, so you may not be able to define the ‘finished product’ of co-creation in advance! What you can do though, is think about what a good contribution might look like. Can you provide examples, or talk through this with your students? Then as the discussion unfolds, you can encourage students to think about their own and each others’ comments – do they build on previous comments, do they bring in new evidence, do they advance the understanding in the room?

Thinking fast and slow

Of course, participation is not just verbal – and not just immediate! Active learning should not mean ‘no time to think’. When considering your learning goals, think about fast and slow modes of interaction – is promptness important or does the topic need deliberation and reflection? Silence can be a powerful tool in the classroom if we can resist the urge to fill the space, and giving students time to think before answering can often lead to more developed responses, as well as being more inclusive for those who are less confident, more reflective and/or working in their second or third languages.

Also, as Sequeira points out, participation can be multi-modal – could your students contribute in other formats? And not just to classroom discussions, but also to decision-making processes (choice of topic etc), and to feedback and evaluation opportunities? Thinking about ‘contribution’ more broadly might help to make these processes more inclusive too.

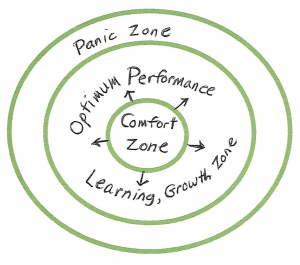

Supporting contribution: ‘productive discomfort’ and ‘brave spaces’

One of the goals of dialogic pedagogies is ‘productive discomfort’ – taking students out of their comfort zone and asking them to examine or defend their views – and being transparent about your pedagogy can also help students to understand this and recognize it in practice. This can be particularly important when working with students who are used to a more transmissive model of education, and are expecting you as the expert to tell them the answers. If your early discussions focus on sharing expectations and you know where your students are coming from, you’ll be able to plan, scaffold and facilitate more effectively.

One of the goals of dialogic pedagogies is ‘productive discomfort’ – taking students out of their comfort zone and asking them to examine or defend their views – and being transparent about your pedagogy can also help students to understand this and recognize it in practice. This can be particularly important when working with students who are used to a more transmissive model of education, and are expecting you as the expert to tell them the answers. If your early discussions focus on sharing expectations and you know where your students are coming from, you’ll be able to plan, scaffold and facilitate more effectively.

It can also help to acknowledge that collective exploration of ideas requires both intellectual and emotional labour, particularly as it can be intimidating to voice aloud ideas that are not fully formed. Much of the literature talks about creating ‘safe spaces’, but again this is an idea that merits a more critical inspection, particularly in the context of recent debates about free speech (‘safe’ for whom?). Another approach to this is the idea of ‘brave spaces’, replacing the comfort and lack of risk implicit in ‘safe’ spaces with an explicit acknowledgment of discomfort and challenge (Arao and Clemens 2013). Whichever approach you choose, creating trust will help to ensure students feel able to contribute, and there are a range of ways to do this, including discussion, modelling and constructive feedback. How you answer a ‘stupid’ question, whether or not you ‘cold call’ students, and how you respond to their input will all inform the norms of the learning space.

“The Socratic professor aims for “productive discomfort,” not panic and intimidation. The aim is not to strike fear in the hearts of students so that they come prepared to class; but to strike fear in the hearts of students that they either cannot articulate clearly the values that guide their lives, or that their values and beliefs do not withstand scrutiny.” (Speaking of Teaching, 2003)

Communication is a two way street

These ideas, and Sequeira’s observation about valuing active listening skills, led me on to the second conversation I want to share. Last week I attended a dissemination event for the ‘Learning Through Listening‘ project, led by Zoe Robinson and Christa Appleton at Keele. The project is looking at using global sustainability issues as an accessible context for developing conversations between individuals from different disciplines. This by itself is a laudable goal, as many of the ‘wicked problems’ of sustainable development will certainly need a interdisciplinary approach if we are ever to solve them. More broadly than that though, the project is also looking at developing active listening skills to support these conversations, and at listening as an area that is undervalued in education and in modern life. The event raised a few key questions for me, which I’ve noted below.

Active listening: the missing piece?

When we talk about communication skills with students, what do we prioritise? I work with many staff writing learning outcomes for our taught modules at Northampton, and much of the language we use for communication skills is proactive and performative: describe, explain, present, propose, justify, argue. Perhaps this is inevitable, as we need to make the learning visible in order to assess it, but there’s no doubt that these terms only give half of the picture of what communication actually is. By focusing so much on the telling, on the transmission of information and convincing of other people, are we giving students the impression that listening is less important? Are we encouraging the development of what Robinson described as the “combative mindset” so prevalent in 2018, and thereby inadvertently discouraging the development of curiosity, openness and willingness to learn from others – peers as well as tutors?

To rebalance the discourse around communication, the project at Keele used a number of activities to support the development of listening skills. One idea that really appealed to me was topping and tailing a series of guest speaker sessions – referred to as ‘Grand Challenges‘ – with a workshop before the lecture and a discussion session immediately afterwards. This allowed the students to think about what they already knew about the topic, and prepare to get the most of out of the session, and crucially also to follow up afterwards by sharing and developing some of the ideas it generated. Other interventions were slightly smaller scale, although perhaps easier to implement at a session or module level. Participants at the event last week got to try out some of these, and although I won’t cover them in detail here, the tasters below might give you some ideas for your classroom.

Learning to listen

One activity asked us to think about major influences that had shaped the way we as individuals see the world. We reflected individually on this, then shared what we felt comfortable with. I’ve never been asked to list these explicitly before, and it was interesting to actually see how everyone’s perspective is unique and created from a distinct combination of personal influences. We also talked about the factors that make it difficult for us to listen, covering everything from environment to agency to cognitive load. It was refreshing to realise that sometimes, everyone is bad at listening – and this was demonstrated when one of the session leads read aloud, probably only about a paragraph, and then pointed out that most of us would miss around half of any message we hear! I won’t spoil the final activity, in case you’re planning to go to one of the events, but also because the team at Keele will be releasing guidance on these as outputs from the project this summer. But needless to say it was fascinating – keep an eye on the website and the project blog for more.

Two more things struck me about the day overall. One was the emphasis on setup of the physical space. We spent part of the day seated in a circle, and part in rows facing a screen. This was a deliberate strategy by the project team and the contrast in terms of conversational dynamic was marked. This reinforced my view that we have the right approach with the classrooms at Waterside – it’s really remarkable what a difference movable furniture can make. The other thing I found interesting is that talking about listening made me (and the other participants too) suddenly very conscious of it. Even after the first activity, I found myself monitoring my communication with the other participants. Maybe it only needs one activity or discussion to highlight the issue, to begin to change how participants communicate?

Scaffolding discussion

The final point I want to make is something that was touched on in both of these conversations, and it’s about effective scaffolding. Both classroom and online discussion is usually more productive once the students have ‘warmed up’, got to know each other or developed a bit of confidence. There are lots of ways to approach this. In the event at Keele, for example, we started with a relatively uncontroversial topic – not many people in a university context will disagree that the UN sustainable development goals are a good thing, although they might disagree about how to address them. This can be a good way to introduce dialogic pedagogies, before working towards more heated or controversial topics (see this guidance from the University of Queensland on using controversy in the classroom). At Keele we also started with group discussion before we moved on to the one-to-one. This might be counter to the usual think-pair-share approach to scaffolding, but it did mean we had all spoken, and had some idea of where others in the room were coming from, before moving into more in-depth discussion. There’s also something to be said for reflecting on your question technique – are the questions you ask opening up or shutting down discussion?

These two conversations have given me lots to think about in terms of how we ‘do’ active learning. If you have any thoughts on this from your own experience, as always I’d love to hear them, so please add them as a comment. One last question to end with, thinking back to your last teaching session. Who in the room didn’t contribute, and why might that be?

References:

Arao, B and Clemens, K. (2013) “From Safe Spaces to Brave Spaces: A New Way to Frame Dialogue Around Diversity and Social Justice”. In Landreman, L.M. (ed.) The Art of Effective Facilitation: Reflections from Social Justice Educators. Sterling, Virginia: Stylus Publishing LLC, pp135-150.

Robinson, Z. and Appleton, C. (2018) Unmaking Single Perspectives (USP): A Listening Project [online]. Available from: https://www.keele.ac.uk/listeningproject/ [Accessed 27 March 2018]

Sequeira, L. (2018) Heresy of the week 2: silence in the classroom is not necessarily a problem. The Education Blog [online]. Available from: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/education/2017/01/19/heresy-of-the-week-2-silence-in-the-classroom-is-no-problem/ [Accessed 27 March 2018]

The move to Waterside is fast approaching, and there are a number of important deadlines this year for us as staff members getting ready for the move. With this in mind, here’s a quick timeline that tries to pull together what’s happening when in preparation for the move. It’s intended to help you see what help is available to you, to support you in meeting these deadlines, and also how you might be able to use some of this work towards another target many of you have for the year – gaining your HEA Fellowship.

The move to Waterside is fast approaching, and there are a number of important deadlines this year for us as staff members getting ready for the move. With this in mind, here’s a quick timeline that tries to pull together what’s happening when in preparation for the move. It’s intended to help you see what help is available to you, to support you in meeting these deadlines, and also how you might be able to use some of this work towards another target many of you have for the year – gaining your HEA Fellowship.

Download the map: Supporting key milestones towards Waterside [PDF]

Of course, different members of staff will have different targets and priorities, and not all of these are reflected here. Some Faculties and subject groups might also have their own internal deadlines for institutional projects like the UMF Review, so always check if you’re not sure. We’ve tried to capture the ones that are generally relevant to most academic staff, but if we’ve missed any, please let us know!

By Dr. Jasmine Shadrack, Senior Lecturer in Popular Music, FAST

As this year’s choir have been asked to perform at the opening ceremony of Waterside, as well as our own performance at the Royal next June, it was important to choose a piece of music that had the wow factor. And for me, that has to be Mozart’s Requiem Mass in D Minor. It was the first piece I ever conducted so I have very fond memories of it. I have also performed it myself as a soprano during my undergraduate degree so my knowledge of it is intimate. The fact that Mozart knew he was dying when he wrote it, makes the piece all the more poignant and special.

As this year’s choir have been asked to perform at the opening ceremony of Waterside, as well as our own performance at the Royal next June, it was important to choose a piece of music that had the wow factor. And for me, that has to be Mozart’s Requiem Mass in D Minor. It was the first piece I ever conducted so I have very fond memories of it. I have also performed it myself as a soprano during my undergraduate degree so my knowledge of it is intimate. The fact that Mozart knew he was dying when he wrote it, makes the piece all the more poignant and special.

The music for it will take a longer time to come together but the choir are making great strides already. We have completed (in the most part!) the Aeternam and the Kyrie Eleison (the first two movements) as well as learning some traditional Christmas carols too (for a lunch time concert later in the term). This time I am joined by a new member of staff, Miss Francesca Stevens who does a two hour vocal training session a week to support what I do every Monday in choir rehearsal. Already I have noticed the bond starting to form, not just between each section of the choir, but as a unit too. One of the things I love most about doing this is watching everyone work together for a common goal. It is active blended learning at every stage, from the rehearsals all the way through to the performance. Not only do they learn close score reading, sight reading , close part harmony, how counterpoint functions, effective breathing techniques, good pronunciation, professional conduct and critical listening, they also forge real solidarity as a cohort that spans across all years of the popular music undergraduate degree.

They are able to exercise their own autonomy by using their voice. This might sound simplistic but it really helps to acknowledge that one voice can have a huge impact on a choir. Through their subjective involvement, they take part and contribute to an objective goal so it is experiential. They also gain empowerment through their learning community. As the choir is voluntary, it means that they are there because they want to be and they are not doing it for assessment purposes. I have tried making it assessable previously and it just didn’t work; it actually undermined all the camaraderie and fun we have with it. There is a real sense of inclusivity too that reflects on their personal responsibility to the choir.

So, at week three of the choir in term 1, we are making great progress and having fun at the same time!

Jasmine will be keeping us up to date with the progress of the choir, but this post is also one in a series of ABL Practitioner Stories, published in the countdown to Waterside. If you’d like us to feature your work, get in touch: LD@northampton.ac.uk

By Nick Cartwright, Senior Lecturer in Law, FBL

I was at a meeting of people involved in various ways in staff development of lecturers and as we as an institution had adopted Active Blended Learning (ABL) as the ‘new normal’ I found myself asking in our break-out group: “ABL WTF?” The response was roughly along the lines of “it’s what you do Nick” and several conversations later I was invited to write this blog post about what I do in the classroom and why.

Firstly, one of the most important answers to the why I teach the way I do is because I enjoy doing it this way and it works well for me and what I teach. I certainly don’t think it’s better than other approaches and I don’t know if it would work for every tutor or every subject.

So, I know what works for me now but it was a long journey. I started teaching the way I was taught within the straight-jacket of institutional policy where I then worked, we had a lecture then a seminar every week for ever every module. The lecture was recorded on VHS tapes and stored in the library, the technology meant I had to use PowerPoint and stand stock still behind the lectern. The hour-long seminars I inherited required that in week 1 we asked the students to read chapter 1 of the assigned text, week 2 was chapter 2 and so on. Students were instructed to answer roughly 10 questions and bring hard copies of their answers. I ran a tight ship, students who turned up unprepared were told to leave – my classroom was an exclusive space for the students that were the easiest to teach. We had roughly 5 minutes on each question then left, job done.

Later in my career, at a different institution, I sat in a staff meeting listening to colleagues report that the foundation students had “gone feral” – a chair had been thrown, a lecturer threatened and they simply would not sit down in two straight rows, shut up and listen as wisdom was dispensed. Of course they wouldn’t, despite being bright and capable and having gone through 13 years of formal education they were in the foundation year because they hadn’t achieved the two D’s necessary to enter straight onto the degree programme. Bored with PowerPoint I found myself eagerly volunteering with a colleague to take on these students who we were to later find out were some of the brightest, most enthusiastic students we’d ever had the pleasure of teaching.

One student in feedback tagged our efforts ‘sneaky teaching’ because without realising it they were learning, we tagged it ‘learning by doing’ and at validation the external panel members commended it. In one module the students formed political parties and competed to be elected, in another they witnessed a train wreck and were the lawyers trying to support the victims, at the end arguing before the European Court of Human Rights that one client had the right to die. We didn’t tell them anything, clients sent letters, senior partners sent emails and we patiently waited for them to ask us to direct them to a source or take through a topic area. That we learn best by doing is nothing new, the Ancient Greek philosophers key principle was that dialogue generates ideas from the learner: “Education is not a cramming in, but a drawing out”1. I came to Northampton burning with a passion to get my students learning by doing because it works and because it engages many students who have been excluded by traditional schooling.

One student in feedback tagged our efforts ‘sneaky teaching’ because without realising it they were learning, we tagged it ‘learning by doing’ and at validation the external panel members commended it. In one module the students formed political parties and competed to be elected, in another they witnessed a train wreck and were the lawyers trying to support the victims, at the end arguing before the European Court of Human Rights that one client had the right to die. We didn’t tell them anything, clients sent letters, senior partners sent emails and we patiently waited for them to ask us to direct them to a source or take through a topic area. That we learn best by doing is nothing new, the Ancient Greek philosophers key principle was that dialogue generates ideas from the learner: “Education is not a cramming in, but a drawing out”1. I came to Northampton burning with a passion to get my students learning by doing because it works and because it engages many students who have been excluded by traditional schooling.

I had started out teaching some more practical topic areas so the ‘doing’ was quite easy to work out but last week I found myself in a first-year workshop dealing with the issues of the nature of law and specifically feminist and queer theory approaches. It was when discussing how that had gone that I was asked to write down how I had done it.

The session needed to get the students to grasp that there are different critical voices within (and outside of) feminism and to get to grips with the skill of applying different perspectives to the law – what they applied the law to was less important. The workshop was two hours long and there were three questions to discuss, we ran out of time in every session and every session was completely different. I could have worried about equality of learner experience, ensuring every student in every session got an identical set of correct notes, and in my younger days I would have done, but my students did get equality of learner experience. They got to choose the lenses through which we discussed the issues, for example one group focused on issues of consent and sexual touching in a social setting, another on the lack of diversity in the judiciary and another on whether the dominant narratives around immigration were racist. It was relevant to all of them rather than just those who related to the lens I would have chosen which would likely be white, male and straight.

The session needed to get the students to grasp that there are different critical voices within (and outside of) feminism and to get to grips with the skill of applying different perspectives to the law – what they applied the law to was less important. The workshop was two hours long and there were three questions to discuss, we ran out of time in every session and every session was completely different. I could have worried about equality of learner experience, ensuring every student in every session got an identical set of correct notes, and in my younger days I would have done, but my students did get equality of learner experience. They got to choose the lenses through which we discussed the issues, for example one group focused on issues of consent and sexual touching in a social setting, another on the lack of diversity in the judiciary and another on whether the dominant narratives around immigration were racist. It was relevant to all of them rather than just those who related to the lens I would have chosen which would likely be white, male and straight.

The biggest challenge is letting go and empowering students to find their own way through the issues, generating authentic knowledge which may be different from or even challenge my knowledge. Practically it also involves what I dubbed in chats ‘double thinking’, keeping two chains of thought going at once. One half of my brain is following the students journey, sometimes disappearing down the rabbit hole, whilst the other is focused on what we need to cover and trying to keep an overview of the topic all the time working out what questions I need to throw out to keep the two tracks running in the same direction – if I lose the latter the session suddenly loses any sense of direction and this disengages my students. It’s more challenging and more tiring than how I used to teach, but I believe it is a better, more inclusive experience for my students. I wonder what I’ll be doing 10 years from now and how critical I’ll be of what I do today?

1Clark, D., ‘Socrates: Method Man’ Plan B [online] http://donaldclarkplanb.blogspot.co.uk/search?q=Socrates [accessed 4 October 2013 @ 14:37]

This post is one in a series of ABL Practitioner Stories, published in the countdown to Waterside. If you’d like us to feature your work, get in touch: LD@northampton.ac.uk

Over the past couple of years, lots of different people have asked me about our curriculum change project here at UoN. From teaching staff and students here at the University, to Northampton locals and parents, and even learning and teaching experts at other universities, there is increasing curiosity around the idea of a university without lectures. The lecture theatre has long been an iconic symbol of higher education, heavily featured in popular culture as well as many university recruitment campaigns. So how to explain why we think that we can do better?

Here are some of the reasons why I think that active blended learning (or “you know, just teaching” as I often hear it described), is the way of the future* for student success. What are yours?

- It’s effective for learning. Pedagogic research tells us that it is important for students to be actively involved in their learning – that is, to have opportunities to find, contextualise and test information, and link it to (or explore how it differs from) their prior understanding. Students who construct their own knowledge develop a deeper understanding than students who are just given lots of information, memorise it for the assessment and then promptly forget it. Who was it that said “Tell me and I forget, teach me and I may remember, involve me and I learn”? There is debate about the source of the quote, but there’s a reason it has endured…

- It can be more inclusive. Writers and educators like Annie Murphy Paul and Cathy Davidson are among many who question whether lecturing as a teaching approach benefits some students more than others – or indeed whether the students who succeed most in lecture-intensive programmes are doing so in spite of (rather than because of) the teaching approach. Now, active blended learning is not an easy fix for this challenge, and if not carefully designed it can also create environments that can disadvantage some learners (noisy classrooms can be difficult for students with language or specific learning difficulties, for example, and online environments can be challenging in terms of digital literacy). But with forethought and planning, ABL can help to ensure that all students have a voice and a role in the learning environment, and evidence suggests that it can reduce the attainment gap for less prepared students.

-

It’s more engaging / interesting / fun! When Eric Mazur used Picard et al.‘s electrodermal study to point out that student brainwaves (which were active during labs and homework) ‘flatlined’ in lectures, he may have been at the extreme end of the argument. But from the student perspective, anyone who has been a student in a long lecture (or who has observed rows of students absorbed in their laptops or phones) knows how easy it is to switch off in a large lecture environment. And from the tutor perspective, anyone who has been tasked with giving the same lecture multiple times knows that interaction and contribution from the students is vital to breaking it up. Smaller, more discursive classrooms allow for variety; for more and different voices and ideas to be shared.

- It scaffolds independence. Our students are only with us for a short time. If we teach them to depend on an expert to tell them the answers, what will they do when they don’t have access to those experts any more? The Framework for Higher Education Qualifications says that graduates should, among other things, be able to “solve problems”, to “manage their own learning”, and to make decisions “in complex and unpredictable contexts”. Our graduate attributes say that our students should be able to communicate, collaborate, network and lead. We don’t learn to do these things just by listening to someone else tell us how.

- It recognises how learning works in the real world. Think about the last time you really tried to learn something new. How did you go about it? You may have been lucky enough to have access to experts in that area, but chances are – even if that’s true – you also looked it up, asked some people, maybe tried a few things out. Probably you synthesised or ‘blended’ information from more than one source before you felt like you’d really ‘got it’. To be a lifelong learner, we need to be able to find and assess information in lots of different ways. This is exactly what our ABL approach is trying to teach.

Our classrooms at Waterside may look different to the iconic imagery commonly used to depict the university experience. But maybe it’s about time…

*Looking back on the development of university teaching, there is some debate around how we got to where we are: around what is ‘traditional‘ and what is ‘innovative’ in teaching; and also on whether the ubiquity of the lecture is a result of the economics of massification rather than the translation of pedagogic research into practice. Although it is always good to keep an eye on how practice has developed, I see no need to replicate these debates here – instead, this post is deliberately intended to be future focused, on how best to move forward from this point.

This video from Dr Rachel Maunder, Associate Professor in Psychology, provides some examples of active, blended learning approaches that Rachel has tried in her modules so far. Rachel shares two different models, one which focuses on linking classroom activity to independent study tasks online, and one which includes some teaching in the online environment in addition to face to face sessions. Rachel also shares useful lessons she has learned from her experiences so far.

If you have questions about either of these approaches, Rachel is happy to take these via email.

This post is one in a series of ABL Practitioner Stories, published in the countdown to Waterside. If you’d like us to feature your work, get in touch: LD@northampton.ac.uk

By Samantha Read, Lecturer in Marketing, FBL

Taking an active blended learning approach to the delivery of my Advertising module for the BA Marketing Management Top-Up programme has enabled me to enhance traditional ways of teaching the subject material for students to make constructive links between areas of learning and engage with theory in a fun and collective way.

Traditionally, I presented the students with a lecture-style presentation of the history of advertising, drawing on examples from the past and present to illustrate how advertising practices have changed over time. The subject material by its very nature is fascinating, from uncovering secrets behind Egyptian hieroglyphics to discussing implications of the printing press and debating the impact of the digital environment on advertising. Yet, without the ability to transport students back in time, it felt as if they were not fully able to appreciate the momentous changes that have taken place within advertising over the years.

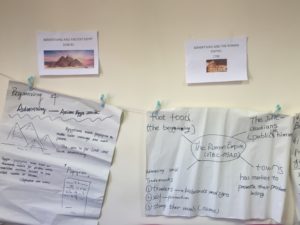

To support the students in learning about the history of advertising this academic year, taking an active blended learning approach, I used a jigsaw classroom technique to facilitate a whole class timeline activity. Before the session, all students were asked to bring in their own device. Following an initial introduction in to the importance of reflecting on the development of advertising over time, I divided the class into seven groups of three or four students. Each group was then given just one piece of the timeline and had 30 minutes to research the implications of that section of history on advertising practice. This included ‘Advertising and Ancient Egypt’, ‘Advertising and the Roman Empire’, ‘The Printing Press was invented’, ‘The development of Billboards’, ‘Radio was invented’, ‘Television was invented’ and ‘The internet was invented’. Students were then given some suggestions of reliable sources where they could go online to research their given time frame and the importance of using these sources and referencing them was stressed.

Whilst the students worked together in their groups to research and construct a one-page A3 poster on flipchart paper outlining their key findings, I circulated the room to check understanding of the research process and the content. This was particularly important as the majority of the students in the class are international students and unfamiliar with UK advertising practices or some terms that they were coming across. I was also able to check the students’ enjoyment of the task and to ensure that everyone in the group was happy to get involved. In contrast to a large lecture style format, the ABL workshop centred on each individual and their specific progression throughout the workshop session.

Upon completion of their A3 poster, each group was instructed to peg their work to the washing line timeline I had attached to the back wall by fitting their time frame within the correct historical period. This ‘active’ jigsaw part of the session not only served a purpose to physically place each time period within its context, but also kept the students engaged in a whole class activity; the success of the timeline ultimately rested with all groups contributing. Once all of the assigned time slots were attached to the washing line, each group selected a member of their group to come to the back of the class to explain their key research findings in relation to the significance of their given time period to the development of advertising throughout history. Having a physical timeline to work with helped sustain the students’ interest in the task and the students themselves were able to make links between each other’s posters, adding to their own and others’ knowledge and understanding.

To ‘blend’ this session to the online environment and subsequently in to the next week’s workshop focusing on the nature of advertising in society, students were asked to complete a survey on NILE which compared print and TV toothpaste advertisements over time. They were also asked to reflect in their online journal on any similarities and differences between the UK based ads included in the survey and those from their home countries. Tutor support and feedback was given on this exercise to ensure that knowledge was accurately embedded and contextualised. Students were also asked to collect three examples of advertisements that they came across over the course of the week as a starting point for a semiotic exercise at the beginning of the next workshop.

Overall, I found the jigsaw classroom technique worked extremely well as part of an ABL approach to teaching the history of advertising. Rather than passively taking in knowledge as I had previously witnessed when delivering this session in the past, there was a real buzz in the classroom. The students were all invested in working together to complete their part of the timeline and were even taking photographs of their completed work. One important aspect of facilitating learning for me is providing opportunities for creativity both in the classroom and online, and taking an ABL approach certainly allows for that.

This post is the first in a new series of ABL Practitioner Stories, published in the countdown to Waterside. If you’d like us to feature your work, get in touch: LD@northampton.ac.uk

As a result of the University’s Active Blended Learning strategy, some teaching staff are considering using some contact time to support learners in the online environment as well as in the classroom. There are many reasons why you might choose to do this: perhaps you want to increase the flexibility for your cohort so they don’t have to travel; perhaps you need to help your students develop their digital literacy; perhaps running a teaching session online allows you to do something you couldn’t do in the classroom (like including a guest speaker, or allowing students time to draft and revise before sharing their thoughts). Or perhaps you just want to add some more structure, guidance and feedback to regular independent study activities.

Whatever your motivation, there are some tips that can help you think about how to use that contact time well, and make online learning a rewarding experience for you and your students.

Transparent pedagogy and clear expectations

Recent research with our students highlighted that they don’t always feel prepared for independent study, and often come to university expecting to ‘be taught’ rather than to have to work things out for themselves (the full report can be downloaded here). Scaffolding the development of independent learning skills is a gradual process, with implications for online as well as classroom teaching – particularly as this way of learning may be new to your students too (at least in formal education contexts). So how do you avoid students feeling like they’ve been ‘palmed off’ with online activities, when national level research tells us that many applicants expect to get more class time than they had at school?

It’s worth setting time aside early on to have frank conversations about how learning works at university level, and about how the module will work, but also about why those choices have been made. Students can sometimes be unaware of the level of planning and design work that goes into a module, so it helps to explain why you’re asking them to do the tasks you’ve planned – in the discussion forum, for example, why is it important for them to engage with opinions or ideas shared by other students? You don’t need to be an expert on social constructivism to explain that learning to research, communicate and collaborate online are crucial skills for graduates. And if it’s the first time you’ve tried something, don’t be afraid to say so, and acknowledge that you’re learning together! Keeping the conversation open for feedback on teaching approaches will help improve them in the future.

It’s worth setting time aside early on to have frank conversations about how learning works at university level, and about how the module will work, but also about why those choices have been made. Students can sometimes be unaware of the level of planning and design work that goes into a module, so it helps to explain why you’re asking them to do the tasks you’ve planned – in the discussion forum, for example, why is it important for them to engage with opinions or ideas shared by other students? You don’t need to be an expert on social constructivism to explain that learning to research, communicate and collaborate online are crucial skills for graduates. And if it’s the first time you’ve tried something, don’t be afraid to say so, and acknowledge that you’re learning together! Keeping the conversation open for feedback on teaching approaches will help improve them in the future.

In conversations about pedagogy, be sure to make space for your students to talk about their expectations and previous experiences. This might help them identify aspirations and areas for development, but it will also inform your planning, and a shared understanding of responsibilities will make the learning process run much more smoothly. Consider co-creating a ‘learning contract’, exploring issues like how often you expect them to check in on social learning activities on NILE, and how (and how quickly) they can expect to get responses to questions they pose there.

Building relationships

A key element of success in any learning environment is trust. This doesn’t just mean students trusting in you as the subject expert, and trusting that the work you’re asking them to do is purposeful and worthwhile (see above). It also means trusting that your classroom (whether physical or online) is a safe space to ask questions, and that feedback from peers as well as from you will be constructive and respectful. Some of this can be explicitly addressed with a shared ‘learning contract’, as above, but it also helps to reinforce this through the learning activities themselves. In the online environment, introducing low-risk ‘socialisation’ activities early on can help to build confidence and a sense of community, which will be invaluable in the co-construction of knowledge later on (see Salmon’s five stage model for more on this). Simple things like adding the first post to kick off a conversation, and explicitly acknowledging anxieties about digital skills, can make all the difference.

Trust also means students trusting that their contributions in the learning space will be acknowledged and valued. Many online tools, such as blogs and discussion forums, are specifically designed with student contribution as the focus, but with live tools, like Collaborate, you may need to plan activities specifically to support this, so that it’s not just you talking. After all, you wouldn’t expect a discussion forum to be composed of one long post from you, so with live sessions, the same principles apply! (see Matt Bower’s Blended Synchronous Learning Handbook for ideas).

Trust also means students trusting that their contributions in the learning space will be acknowledged and valued. Many online tools, such as blogs and discussion forums, are specifically designed with student contribution as the focus, but with live tools, like Collaborate, you may need to plan activities specifically to support this, so that it’s not just you talking. After all, you wouldn’t expect a discussion forum to be composed of one long post from you, so with live sessions, the same principles apply! (see Matt Bower’s Blended Synchronous Learning Handbook for ideas).

On the flip side of this, you also wouldn’t expect a student who was speaking in a live webinar to keep trying if they didn’t get a reply. So using the same principles, if you’re planning asynchronous (not live) learning activities, make sure you schedule teaching time to review your students’ views and ideas, whether online or in the next face to face session. Online, techniques like weaving (drawing connections, asking questions and extending points) and summarising (acknowledging, emphasising and refocusing) are invaluable, both for supporting conversation and for emphasising that you are present in the online space (see Salmon 2011 for more on these skills).

And if some of your students haven’t contributed, don’t panic! There could be lots of reasons for this. It may be a bad week for them, or a topic they don’t feel confident in, in which case chances are they will still learn a lot from reading the discussion. It may be that someone else already made their point – after all, if you were having a discussion in the classroom, you wouldn’t expect every student to raise a hand and tell you the same thing (if you need to check the understanding of every single student, maybe you need a test or a poll instead of a discussion). If participation is very low though, it may be that you need to reframe the question (as a starter on this, this guide from the University of Oregon, although a little outdated in technical instructions, includes some useful points about discussion questions for convergent, divergent and evaluative thinking).

Clarity, guidance, instructions, modelling

Last but by no means least, with online learning it helps to remember that students need to learn the method as well as the matter. A well-organised NILE site, clear instructions and links to further help will go a long way, but nothing beats modelling. Setting aside time in your face to face sessions to walk through online activities and address questions will save you lots of time in the long run.

I recently read an insightful piece from Charles D. Morrison, which argues, among other things, for a clear distinction between ‘information’ and knowledge’ in educational discourse. Morrison, like many others, holds that while information may be transferred (e.g. through telling or lecturing), knowledge cannot – that is, information must be contextualised, applied, experienced in order to become knowledge. This will be a familiar point to anyone interested in effective pedagogy, but the article is worth a read, not least because it communicates clearly the responsibilities of this for the student as well as the tutor. It’s also a point that bears repeating at this time of year, as we consider the new cohorts of students who have already begun to walk in to our classrooms.

Everyone, students and tutors alike, will bring something slightly different to the classroom. There will be differences in the prior knowledge and skills students have developed, but there may also be differences in the ways these are integrated into their experience – the preconceptions (and misconceptions) they have created in order to make new information make sense to them. This collection of intellectual baggage is what Phil Race refers to as ‘learning incomes’ – and it can really make a difference to how each student engages with new learning, even in the most carefully designed and structured learning activities. How then to ensure that each of these individuals can progress towards common intended outcomes?

Everyone, students and tutors alike, will bring something slightly different to the classroom. There will be differences in the prior knowledge and skills students have developed, but there may also be differences in the ways these are integrated into their experience – the preconceptions (and misconceptions) they have created in order to make new information make sense to them. This collection of intellectual baggage is what Phil Race refers to as ‘learning incomes’ – and it can really make a difference to how each student engages with new learning, even in the most carefully designed and structured learning activities. How then to ensure that each of these individuals can progress towards common intended outcomes?

Race argues that the best way to do this is to ask them what they already know, using one of our favourite tools here in Learning Design, the humble post-it. In the piece linked above, he describes a simple exercise designed to collate students’ thoughts on the most important thing they already know about a topic, and the biggest question they have. This kind of exercise is useful for helping teaching staff to identify knowledge gaps and misconceptions, but Race also points out another important gain: that “Learners are very relaxed about doing this, as ‘not knowing’ is being legitimised”. This can be particularly important for new students, who may lack confidence in their abilities, because it frames the classroom as a safe space for exploration, experimentation and failure (often a necessary precursor to success!).

If you’re thinking about using a similar diagnostic activity with your new learners this term, you might also find this post from Janet G. Hudson useful, as it includes a few more suggestions on how to gather data on common misunderstandings in your subject. Or, if you’re already using this type of activity, why not share your thoughts below on what has worked well for you?

Recent Posts

- Blackboard Upgrade – July 2025

- StudySmart 2 – Student Posters

- NILE Ultra Course Award Winners 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – June 2025

- Learning Technology / NILE Community Group

- Blackboard Upgrade – May 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – April 2025

- NILE Ultra Course Awards 2025 – Nominations are open!

- Blackboard Upgrade – March 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – February 2025

Tags

ABL Practitioner Stories Academic Skills Accessibility Active Blended Learning (ABL) ADE AI Artificial Intelligence Assessment Design Assessment Tools Blackboard Blackboard Learn Blackboard Upgrade Blended Learning Blogs CAIeRO Collaborate Collaboration Distance Learning Feedback FHES Flipped Learning iNorthampton iPad Kaltura Learner Experience MALT Mobile Newsletter NILE NILE Ultra Outside the box Panopto Presentations Quality Reflection SHED Submitting and Grading Electronically (SaGE) Turnitin Ultra Ultra Upgrade Update Updates Video Waterside XerteArchives

Site Admin