At least 1 in 5 people in the UK have a long term illness, impairment or disability. Gov.uk (2018). In the academic year 18/19, just under 1000 University of Northampton students were actively using ASSIST services. This does not include students who may be registered with the Mental Health service but not ASSIST, nor those who have chosen not to disclose. Making your materials more accessible can help people with:

- impaired vision

- motor difficulties

- cognitive impairments or learning disabilities

- deafness or impaired hearing

For any resources you provide to your students, whether online, printed, or displayed in class, it is your responsibility to ensure they are accessible. This blog post acts as an introduction for teaching staff who are unfamiliar with making accessible content. My top 5 tips include:

- Clear Colours.

- Logical Layout.

- Eliminate Expressions.

- Image information.

- Descriptive Details.

1. Clear Colours

Accessibility standards specify a contrast ratio between text and background. The ratio can be lower when the text is larger. I would recommend only placing text on a strong colour for headlines or titles. I’ve included a link to a contrast checker at the bottom of the blog post.

When it comes to being able to read longer pieces of text easily, black text on white background seems to be accepted as the clearest combination. But for many people, such a stark contrast can make the text appear to skate about on the surface of the page. Using a very dark grey instead will help alleviate this. Some people find a pale coloured background really helps too. Ask your students if they prefer a pale blue or cream background colour behind text on your PowerPoint slides. Use Bold type to emphasise important words or phrases in the sentence, rather than using red. Finally, avoid placing text over an image, unless there is very clear contrast.

2. Logical Layout

This is one that will help most of your students. Make sure you describe things clearly and without ambiguity. For example, instead of putting a link to a journal article on NILE and write in brackets underneath, “you need to be logged into NELSON”; you should first explain how to log into NELSON. Obviously, this is just an example and third-year students can probably be expected to know how to log in to NELSON if they’ve done it before.

Another example is having content folders on NILE saying Week 1, Week 2, Week 3 etc. The folders are clear, consistent and not cluttered. Ensuring sites meet the NILE standards (see link below) means students have consistency across all the sites they use and can find what they need quickly and easily.

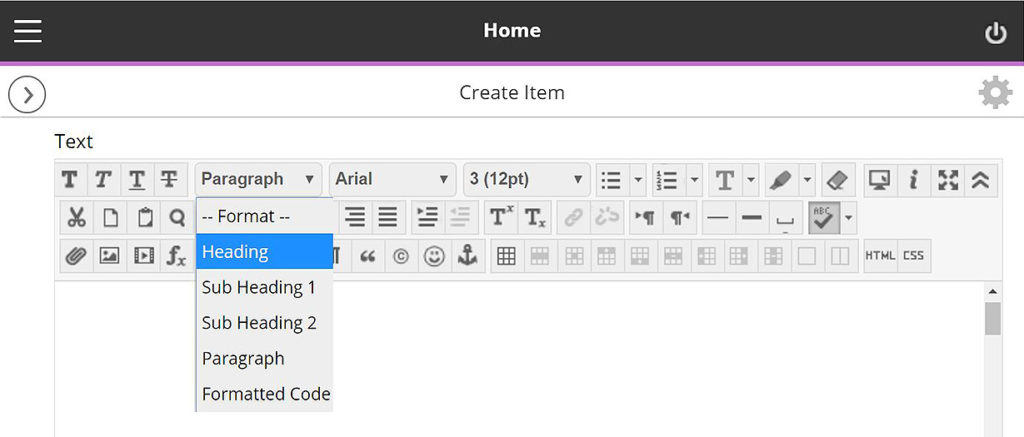

On NILE you can pick heading styles to help everyone using screen-readers. When you build a content Item, for example, there are options in the toolbar to let you change from Paragraph to Heading or Sub Headings. Use these instead of simply changing the size or making them bold. You can still change the size once you’ve set it to be heading/sub headings.

With larger pieces of text, the use of accurate, meaningful headings and subheadings can help students who feel overwhelmed by a sea of text and make it easier when people come back later on to find something. Learn more about how to use heading styles in the staff development training ‘Creating Accessible Online Content’. A link to more information about this is included at the end along with a download link to the ‘Designing for Diverse Learners’ posters, which explain all of this and more.

3. Eliminate Expressions

This is vital for the most important information and giving instructions. Following on from the previous step where we are making efforts to avoid ambiguity, the use of expressions or idioms can cause confusion or be completely undecipherable by others. Bear in mind, a lot of expressions taken literally word for word, make no sense at all.

Example 1:

“You will be assessed in just two weeks. It’s time to pull your socks up!”

I’m not sure how my socks relate to the assessment, much less the slouchiness

of them.

Example 2:

“You have been working really hard all year, don’t throw it all out the window now”.

Throw what out of the window? I wasn’t planning on throwing anything out of my window.

Example 3:

“You seem to have grasped the wrong end of the stick”.

What stick? I don’t remember any stick.

Similarly, avoid sarcasm and subtle exaggeration. Present information, clearly, simply and factually.

Besides certain groups of people taking them too literally, many expressions are becoming old-fashioned and you’ll find your younger students will have never heard them before. In these cases, they can identify that it is an expression and it shouldn’t be taken literally —but they still won’t know what it means.

Your challenge for the rest of the day is to make a mental note of every time you use an idiomatic expression. You might be surprised how much you do it.

4. Descriptive Details

Again, with giving instructions or perhaps announcements from your NILE site, make your expectations are clear, without making assumptions. For example, if you have students booked in for tutorials, make sure you tell them to arrive early, how long they have and what will happen if they turn up late.

They say a picture is worth a thousand words. I can’t help thinking this is a slight exaggeration. The key with this one is not to assume everyone will interpret the image in the same way. Just as you might teach your students to interpret data on a graph; when using images to convey information, make sure you explain what the picture is and what it’s there for. If you use a screenshot, for example, make sure we know what we’re looking at within the image. More importantly, don’t just put an image in place of any explanation.

Ideally, any images or charts should be there to enhance or add meaning to what you have said or written. In fact, most people benefit from something pictorial to illustrate the concept. However, if the image is there for purely decorative purposes, that’s fine and that brings us onto the number 5.

5. Image Information

In addition to people who won’t interpret an image the same way you do, there are those with visual impairments who can’t see the image at all. If you’ve followed the previous advice, you’ve already helped these people. However, there is standard practice for using images on the web, which are outlined in the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), see link below. When you upload an image to NILE, you will see two boxes just above the image preview. One says Image Description and the second one says Title. Give the image a relevant title and the description needs to contain the essential information. Think about why the image there, the information it presents, and then decide which words you can use to convey the same function and/or information. Leave the description blank if the image is for purely decorative. Get into the habit of doing this and it will become second nature. To help you with this, the Blackboard Ally tool has been applied to our NILE sites. You may have noticed a small gauge icon next to items you have uploaded. If you see a red/low gauge next to one of your images, click on it to find out how to improve its accessibility. Click the link at the end, to download Guidelines for Creating Accessible Word Documents. This is great resource for you to save a refer back to.

Caution: If you use an image that contains text, screen-readers will not be able to identify the words. Therefore, you must make sure any essential text from the image is also included as text. Try to select the text on the image below. You will see that you can because the text is not part of the image. In the previous images in this blog post, the text is part of the image.

Remember to book onto the staff development training session to learn how to make your Word docs and PowerPoints accessible too.

Find details on Unify in ‘staff development and training’.

Just 5 suggestions to help you support your students

In closing, please note I have deliberately avoided mentioning specific impairments, difficulties or disabilities in any of the sections. This is because I believe implementing each of these ideas can help all of your students, regardless of any additional needs. I strongly believe making accessible content should be about helping and supporting your students, not purely for the sake of meeting legislation.

It’s up to you to have an open dialogue with your particular students to find out ways in which you can support them. They do not have to disclose anything to you, and those who have declared something on their application probably won’t realise that information isn’t automatically passed onto their lecturers.

If you have content on Edublogs, please meet with your Learning Technologist before Sept 2020 for advice on making your Edublogs sites meet accessibility standards.

These were just my top 5 simple ways to get started, please leave a comment to let us know what tips and strategies you recommend. Thank you for reading and check out the links below if you want to learn more.

Further reading:

- JISC – UK law on accessibility

- GOV.UK – Understanding new accessibility requirements

- Creating content that works well with screenreaders

- WebAim – Contrast checker

- Designing for Diverse Learners. Posters

- AskUs – Editing Kaltura Captions

- AskUs – What is the new Ally accessibility tool in NILE?

- NILE Design standards 19/20

- Unify – Creating Accessible Online Content

The big Kaltura news for September is that users will now begin to have automatic machine-generated (ASR) Closed Captions created for any new video uploaded to their MediaSpace account. This is a significant step forward in making our learning content accessible to all our students.

When the captions are created, the CC icon will appear at the bottom of the video player, and viewers just need to select the icon to read them. If the captions are not 100% accurate, the video owner can correct them using the Kaltura Caption Editor within MediaSpace. There is a handy FAQ which explains how to edit the captions.

The many thousands of videos created before September will also be getting Closed Captions during the autumn to bring us in line with new accessibility legislation. In the meantime, if any videos created pre-September need captions, the Learning Technology team can help process priority caption requests.

Finally, if a student is referred from ASSIST and needs course videos captioned and the machine captions aren’t available or accurate enough, the Learning Technology team can authorise a special request for professional human-created captions to be created.

It’s important our video content is accessible to all our students and the Closed Captions project is going to help achieve that. If you have any questions about Closed Captions at Northampton, then email the Learning Technology team at learntech@northampton.ac.uk

The upgrade during summer 2019 has brought with it some new features. Please find a summary and links to further information below. If you are interested in any of these features and would like more support to use them, please get in touch with your learning technologist

Create a voice recording as feedback

Similar to the voice recording in Turnitin Feedback Studio, instructors can now also use a voice recording feature when marking submissions in the Blackboard assignment type. Please note that if you wish to use a voice recording for feedback, the tool native to the assignment type should be used, i.e. Turnitin Feedback Studio for Turnitin submissions and Blackboard grade centre feedback for other assignments. More details can be found here: https://help.blackboard.com/node/25091

Record attendance in NILE

Please note that this new feature is not linked to any other University system. Instructors wishing to record attendance are able to do so in their NILE module and export a spreadsheet for records. https://help.blackboard.com/node/25071

In this short video Academic Librarian Joanne Farmer explains how academics can best use Aspire reading lists to engage their students.

Aspire Readings lists are created and maintained by module tutors. They are added to each module site and can contain links to books, e-books, journals and audiovisual resources.

Joanne says “reading lists are an important part of the student learning journey and often a starting point for any research or work undertaken. It is worth spending time developing reading lists so students are encouraged to engage with a range of resources”. She cites Rob Farmer’s reading list –

An Introduction to Climate Change for Non-Scientists and Non-Specialists, as a good example to look at for ideas as it has an engaging narrative and structure.

The creation and updating of reading lists are supported by the Academic Librarians who can be contacted by email: librarians@northampton.ac.uk

In this ABL Practitioner Story, Grant Timms (Senior Lecturer in Marketing) reflects on his use of the Kaltura video recorder and streaming platform to create videos and video quizzes to support student engagement.

Grant shares his feelings on the importance of considering the needs of the audience, how analytics help him track audience engagement, and how to stand out in a digital world where students attention is often hard to catch.

The Kaltura Capture recorder and the MediaSpace video streaming platform are available to all staff and students at the University of Northampton. A link and an introduction can be found on the NILE Help tab, under Tools & Resources.

If you’re inspired by his experiments with video quizzes then contact your Learning Technologist for training and support, or explore on your own by reading this FAQ.

http://askus.northampton.ac.uk/Learntech/faq/188945

Case study produced by Learning Technologists Al Holloway and Richard Byles.

Abbie Deeming, Senior Lecturer in Education, has been commended by students and external examiners for her assessment guidance and feedback, and use of marking rubrics. These rubrics meet the University’s requirement to mark to learning outcomes, and make the criteria used in marking clear to students, which is one of the questions that students are asked on the National Student Survey.

“By providing students with clear guidance and good quality, consistent feedback that is personalised and tailored to the individual and which includes links to helpful ‘feedforward’ resources, we are seeing an increase in students better reaching their potential. As a team, we are working to ensure that this excellent practice is represented throughout all modules in the Foundation Degree in Learning and Teaching (FDLT).”

Abbie Deeming

Feedback from Students

Regarding the use of rubrics on the FDLT programme, comments from students were very positive.

“I found the marking rubric very helpful to see how I met the criteria for each LO [Learning Outcome] and for what I need to be more careful with in the future.”

“The rubric is very clear and helpful. Being presented as a grid means it’s easy to read and can be used as a checklist when reading through assignments before submitting. The feedback is really detailed and helpful. I know now what I need to focus on to improve my next one!”

“I found the marking rubric very useful as it clearly outlines what needs to be covered within the assignment. I could also find the little fine details within the marking rubric too, even the formatting. The feedback I found very useful too. In fact I would like to email my appreciation. Overall the feedback was very good as it broke down everything that needs to be improved on, whilst also highlighting the excellent bits from the assignment. Although the feedback was “savage”, I understand it has to be to help us as writers improve. Thank you.”

“I thought that the feedback was very useful. I keep looking back at it then looking at my report to see what I can improve. It was very helpful and hopefully next time I improve. Many thanks.”

“The rubric gave me lots of confidence as I was able to easily see what my strengths were. Overall, I’m thrilled with the feedback. I’m under a lot of stress at the moment but I’m pleased I’ve still produced a good piece of work.”

Example

Below is a copy of the assessment guidance and the marking rubric, created for PDT1065: Pupil Engagement and Assessment. The purpose of the module is to engage students in studying the theory and practice of supporting learning, the assessment of learning and of learner needs, and principles of planning to advance learning. It also provides students with the opportunity to develop their own study skills. The assessment is a 3,250 word report, exploring both formative and summative assessment, reflecting on current practices within a setting and referring to relevant literature on the subject of assessment.

PDT1065 Assignment Brief and Rubric

Recommendations

- Firstly, determine what exactly are we looking for in this assignment, and how do we make this explicit.

- Break down the module learning outcomes against grading criteria to create a rubric which makes it clear what the assignment must look like to equal a pass, merit, or distinction.

- Communicate this clearly and consistently to students – they will be more likely to achieve better grades.

- Make the assessment guidance and criteria used in marking clear to students in the assignment brief

- Advise students to look at the distinction column of the rubric, and to make this into a ‘to do’ list.

- In taught sessions, help students make the connection between the session content and the learning outcomes.

- Following each session, suggest readings for students to look at in more depth to help strengthen their assignment.

- Arrange a tutor and learning development-led session on the theme of ‘understanding your assignment’.

- Ensure consistency across the module team, including partnering with associate lecturers to talk through the learning outcomes, and to explain the ethos behind the use of a marking rubric, i.e., clear guidance and consistency.

- You will find that marking to LOs helps the marking tutor as well, as there is clear guidance on where the mark falls.

- Overall comments should be positive, detailed, and helpful. Aim to give between two and four action points (feedforward), depending on the student and grade. At the next assignment, ask students to note how they have responded to these points.

- On the assignment post date, send an announcement via NILE, offering individual tutorials if clarification is needed on action points.

Feedback from External Examiner

Extract from Summer 2018 Report on PDT1065

Section A2: Measuring achievement, rigour and fairness:

- “Assessments are flexible and inclusive and allow for a range of different responses based on the students’ workplaces and experiences.”

- “Assessments are tightly and clearly linked to the learning outcomes.”

- “The quality and quantity of written feedback to the students is a major strength of this course. As I found last year, feedback is universally positive, detailed and helpful.”

“In talking to colleagues on the course, it is clear that they feel very strongly that this is an integral part of the process of teaching and supporting their students to the best of their ability.”

Further reading

- Dylan William (2009) Assessment for Learning: Why, what and how? Institute of Education

- John Hattie (2008) Visible Learning. Routledge

- Shirley Clarke (2008) Active Learning through Formative Assessment. Hodder Education

Image – Pixabay, no attribution required.

I was recently asked about the Copyright exception ‘Fair Dealing’ and what this means when uploading media content such as videos, podcasts and images within a VLE such as NILE.

As an experienced web designer my understanding of copyright is based on knowledge of online publishing rather than use in Education and therefore I was interested in finding out exactly what this means, and how it applies to our VLE – NILE.

But, before I begin looking at this, I’d like to signpost you to Iain Griffin’s comprehensive post ‘Copyright and online publishing‘. (1) which explains the functions of copyright and contains links to a wide range of online resources which are freely available and can be legally included in any teaching materials without infringing copyright.

What does the term ‘Fair Dealing’ mean?

The UK government’s guidance ‘Exceptions to copyright: an overview‘ (2) include a number of possible exceptions to copyright which come under the term ‘Fair dealing’:

- Caricature, Parody or Pastiche

- Quotation

- Research and Private Study

- Text and Data-Mining

- Archiving and Preservation

- Public Administration

- Accessible formats for disabled people

(Information on each of these is covered in the guide above).

The guide also states that ‘Fair Dealing’ is only applicable when no other licence is in place. so existing licences such as the CLA (Copyright Licensing Agency) (3) for books and journals, ERA (Educational Recording Agency) (4) for off-air broadcast recordings, and other licences such as those with third-party educational providers all take precedence.

From the government document Exceptions to copyright: Education and Teaching (5) I have pulled out a few key points that I think help in our understanding of how this law applies to a VLE.

- Understanding the term ‘Fair Dealing’

‘Fair dealing’ is a legal term used to establish whether a use of copyright material is lawful or whether it infringes copyright. There is no statutory definition of fair dealing – it will always be a matter of fact, degree and impression in each case. The question to be asked is: how would a fairminded and honest person have dealt with the work? - Fair dealing includes the use of multimedia content.

Fair Dealing… ‘permits minor acts of copying for teaching purposes, as long as the use is considered fair and reasonable. So, teachers will be able to do things like displaying webpages or quotes on interactive whiteboards, without having to seek additional permissions.’ - ‘Fair dealing’ is not a way of avoiding licensing.

The majority of uses of copyright materials continue to require permission from copyright owners, so you should be careful when considering whether you can rely on an exception, and if in doubt you should seek legal advice. - Is Fair dealing internationally recognised?

No. Copyright is a territorial right, and different acts are permitted in different countries. You need to ensure that you comply with the laws of the countries in which you provide online resources.

Relevant sections from The Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The ‘Illustration for instruction’ exclusion is referred to in a post on copyrightuser.org (6) by Ruth Soetendorp and Bartolomeo Meletti.

This is from Section 32 of the ‘Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988‘ (7), and includes three stipulations:

- The use of materials must be ‘minor and fair’.

- The inclusion of materials must not undermine sales.

- Appropriate acknowledgement of authorship must (where possible) be given.

JISC’s guidance on ‘Fair Dealing‘ (8) (Joint Information Systems Committee) states that ‘Under Section 32 CDPA – ‘Illustration for instruction’, it is valid for a lecturer to use extracts from ‘films, sound recordings and broadcasts as well as text, music and artistic works to illustrate a teaching point.’ However, is unclear on whether this applies within a classroom or in a VLE.

The reason for the lack of clarity is because in the original legislation The Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the updated The Copyright and Rights in Performances (Research, Education, Libraries and Archives) Regulations 2014 (9) neither is specific to where this exception ‘illustration for instructions’ applies.

Confusingly, in the more recent legislation (2014) there is specific mention of use in a ‘secure electronic network accessible only by the establishment’s pupils and staff’, but only in Sections 35 and 36.

Section 35 covers the use of ‘broadcast’ materials – which are most likely already covered by University’s ERA license, and Section 36 ‘Copying and use of extracts of works by educational establishments’ stipulates that this does not include ‘artistic work’ or ‘broadcast’ materials, and therefore is more likely to be most relevant to materials such as books and journals which are also already covered by the CLA.

As mentioned previously the ‘Fair Dealing’ exceptions only come into play when existing licences do not exist, so this may explain why these exclusions not included in JISC or copyrightuser.org’s guidance and the older ‘illustration for instruction’ is more widely cited.

Examples of how other Universities interpret copyright exceptions.

The points above are interesting because available ‘Fair dealing’ guidance published online by other UK Universities’ most commonly mention the exception Section 32 ”illustration for instruction’. However, the guidance is not consistant across the sector.

The University of Cambridge web page; ‘Copyright and VLE’ (10), proposes that (their) academics are permitted to use short extracts from ‘literary and musical works, films, sound recordings and broadcasts as well as artistic works to illustrate or reinforce a teaching point in lectures and in restricted intranets such as Moodle, provided the original source is explicitly acknowledged’, on the condition that access is ‘limited to those receiving the instruction, preferably to those enrolled on a particular course of study’, and materials are not made available on outward facing web sites such as faculty, departmental or social media.

Staffordshire University’s’ Copyright Guidance (11) takes a similar approach and suggest that it is permissible to take clips off a DVD and upload to a VLE for the purposes of ‘ illustration for instruction’, if the three stipulations in Section 32 are met. They also consider the restriction of learner access to the VLE – a secure network, as a factor in whether the use is considered ‘fair’, and extend their guidance the use of images and lecture capture where copyright materials are used to ‘illustrate a teaching point’.

Guidance on embedded media in Brunel University Library’s post ‘Can I use YouTube content for teaching in Blackboard Learn?’ (12) suggests that embedding a YouTube clip in a VLE is more complex than viewing it as an individual, as sharing a YouTube clip with multiple users ‘may be in breach of UK copyright law as a secondary infringement’. As a result, they go beyond YouTube’s recommendation (13) that the educator should request permission from the uploader, and suggest they should also check that ‘the person granting permission is authorised to do so’.

Fair Dealing at the University of Northampton.

Head of Academic Services (Library and Learning Services), Georgina Dimmock, has provided guidance on copyright exceptions and fair dealing, which can be found on the LLS Copyright (14) web pages. Due to the complexity of the law, and how the fair dealing exceptions can be used with Higher Education, SCONUL (Standing Council on University and National Libraries) is looking to commission a copyright expert to advise on how libraries can use exceptions to support teaching and learning in institutions. (15)

Georgina notes that when using a Fair Dealing exception, it is the responsibility of an academic to make a decision on whether it is ‘Fair dealing’, and individual academics must consider the risks of material uploaded to a VLE.

What action may be taken?

JISC’s guidance Enforcement of copyright, (16) advises that the copyright holder must take legal action against the person they believe has infringed their rights, and by applying to the course the individual can;

- Stop a person making further infringing use of the material by seeking an injunction, interdict or other order.

- Claim damages from those who infringe their copyright.

- Require the infringing party to give up or destroy the infringing.

As the UK Law is based on the principle of ‘Common Law‘ (17) any successful cases will set a precedent for future prosecutions, a point that is driven home on a post on the Conversation.com (18) web site details how a Canadian University has been successfully prosecuted under copyright law and, ‘must pay millions of dollars in licensing fees..’ as a result of a ‘more restrictive interpretation of fair dealing when it comes to educational materials’.

While this international case does not affect UK case law, it does highlight that should a copyright prosecution successfully argue that ‘illustration to instruction’ does not apply to online distribution in a VLE, UK Universities may be required to take a harder line with staff’s use of copyrighted materials in the future.

Copyright risks and alternatives.

As any use of copyright materials contains an element of risk, it would be advisable for staff to consider whether there are licensed alternatives available such as BoB (Box of Broadcasts) (19) which contains over 2 million recordings covered by our ERG licence, or to filter the search in platforms such as YouTube for materials that licensed under a Creative Commons license. (20) and are attributable to a reliable source such as TedTalks (21) or YouTube Education (22) where the copyright holder can be reliably identified.

Where media is only available without a creative commons license, an academic will need to make a decision on whether ‘Fair dealing’ applies, if they believe so, they should be knowledgable of restrictions of the exclusion ‘Illustration for instruction’ and ensure that any media used is; minor and fair, does not affect the potential sales of the copyright holder, and that attribution is given correctly.

When considering this I suggest it’s advisable to imagine yourself before a judge: do you think you could argue successfully that your use of materials under illustration for instruction fits into all of these criteria?

Post Contributors:

Richard Byles – Learning Technologist.

Georgina Dimmock – Head of Academic Services (Library and Learning Services)

References:

(1). Griffin, I., 2015. Copyright and online publishing. The University of Northampton. [ONLINE] Available at: http://blogs.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/2015/06/05/copyright-online-publishing/. [Accessed 6 March 2019].

(2). Intellectual Property Office Online. 2014. Exceptions to copyright: An Overview. [ONLINE] Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/448269/Exceptions_to_copyright_-_An_Overview.pdf. [Accessed 6 March 2019].

(3) CLA (Copyright Licensing Agency Limited). 2019. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.cla.co.uk/higher-education-licence

(4) ERA (Educational Recording Agency) 2019. [ONLINE] Available at: https://era.org.uk/the-licence/

(5) Intellectual Property Office Online. 2014. Exceptions to copyright: Education and Teaching. [ONLINE] Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/375951/Education_and_Teaching.pdf. [Accessed 6 March 2019].

(6) Soetendorp, R and Meletti, B. Unknown. Education. Copyrightuser Organisation[ONLINE] Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/375951/Education_and_Teaching.pdf. [Accessed 6 March 2019].

(7) UK Gov. 2014. Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/48/part/I/chapter/III/crossheading/education. [Accessed 6 March 2019].

(8) JISC. 2014. Exceptions to infringement of copyright. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/copyright-law/exceptions-to-infringement-of-copyright. [Accessed 6 March 2019]

(9) UK Gov. 2014. The Copyright and Rights in Performances (Research, Education, Libraries and Archives) Regulations 2014 [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2014/1372/regulation/4/made [Accessed 11 July 2019]

(10) University of Cambridge. 2019. Scholarly Communication: Copyright and VLE. [ONLINE] Available at: https://osc.cam.ac.uk/copyright/copyright-and-vle. [Accessed 6 March 2019]

(11) Howlett, S. 2017. Copyright Guidance Staffordshire University. Staffordshire University Library.[ONLINE] Available at: https://libguides.staffs.ac.uk/c.php?g=143453&p=937822. [Accessed 6 March 2019].

(12) Ritchie, M. 2014. Q. Can I use YouTube content for teaching in Blackboard Learn? [ONLINE] Available at: https://libanswers.brunel.ac.uk/faq/13827 [Accessed 6 March 2019].

(13) Google/YouTube Support. Unknown. Educator resources. [ONLINE] Available at: https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2802327?hl=en. [Accessed 6 March 2019].

(14) UoN Library and Learning Services. 2019. [ONLINE] LLS Copyright: Copyright and licensing in Higher Education: Copyright exceptions and fair dealing. Available at: http://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/copyright/copyright_exceptions [Accessed 11 July 2019]

(15) SCONUL. 2019. Call to action: developing a copyright briefing – Wed, 23 Jan 2019. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.sconul.ac.uk/news/call-to-action-developing-a-copyright-briefing. [Accessed 6 March 2019].

(16) JISC. 2017. Copyright law. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/copyright-law. [Accessed 6 March 2019].

(17) Bodleian Libraries University of Oxford. 2018. United Kingdom Law: Case law. [ONLINE] Available at: http://ox.libguides.com/c.php?g=422832&p=2887381. [Accessed 6 March 2019].

(18) Bannerman, S., 2017. Why universities can’t be expected to police copyright infringement. The Conversation Trust (UK) [online]. Available from: https://theconversation.com/why-universities-cant-be-expected-to-police-copyright-infringement-82677. [Accessed 6 March 2019].

(19) Learning on Screen – the British Universities and Colleges Film and Video Council. Box of Broadcasts. 2019. [ONLINE] Available at: https://learningonscreen.ac.uk/ondemand

(20) National Copyright Unit Australia. Unknown. How to find Creative Commons Material using YouTube. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.smartcopying.edu.au/open-education/creative-commons/creative-commons-information-pack-for-teachers-and-students/how-to-find-creative-commons-material-using-youtube. [Accessed 6 March 2019].

(21) Ted talks. Unknown. Ted Talks Youtube Channel [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/user/TEDtalksDirector

(21) YouTube Learning. Unknown. YouTube Learning Channel [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/education

NILE is integrated into the Active Blended Learning (ABL) process at The University of Northampton and we need to ensure that it is being used effectively by staff in order to provide a quality student experience.

Building on the guidance which was initially produced in January 2012, the framework has now been updated to cover the minimum standards which are expected on a NILE site. This was approved at University SEC in March, 2019 and is subsequently being used as the basis for the new NILE templates which have been developed for the 2019/20 academic year.

[Post published on behalf of Ale Armellini]

The purpose of this paper is to introduce an evidence-based, transferable framework of graduate attributes and associated university toolkit to support the writing of level-appropriate learning outcomes aligned to Active Blended Learning (ABL), Northampton’s approach to learning and teaching. An iterative process of co-design and co-development was employed to produce both the framework and the associated learning outcomes toolkit. There is tangible benefit in adopting an integrated framework aligned to the principles of ABL, which enables students to develop personal literacy and graduate identity. The toolkit enables staff to write assessable learning outcomes that support student progression and enable achievement of the framework objectives. Embedding the institutional Changemaker attributes alongside the agreed employability skills enables students to develop and articulate specifically what it means to be a “Northampton graduate”. The uniqueness of this project is the student-centred framework and the combination of curricular, extra- and co-curricular initiatives that provide a consistent language around employability across disciplines. This is achieved through use of the learning outcomes toolkit to scaffold student progression.

See the full paper on the framework of graduate attributes and ABL

Keywords: Active blended learning, ChANGE, COGS, Employability and entrepreneurship, Graduate identity, Personal literacy, Active Blended Learning, ABL.

In this new ABL Practitioner Story, Clare Allen (Lecturer in Organisational Behaviour) shares her experience and thoughts on using Padlet in her teaching to support open group discussion.

At the beginning of the year, she asked the students to discuss in small groups what they thought learning was and to use Padlet to upload an image that best represented the thoughts of their group.

Clare talks about how she introduced this new tool to her students, why she found Padlet more engaging than simply delivering PowerPoints slides and what impact she feels it made on students understanding of their subject.

Listen to Clare in conversation with Richard Byles and Al Holloway, Learning Technologists for the Faculty of Business and Law, and if you’re interested in exploring how Padlet could support your teaching then copy the following link into your browser:

http://askus.northampton.ac.uk/Learntech/faq/186022

Padlet is available free to all staff and students at the University of Northampton and can be found on the NILE Help tab, under Tools & Resources.

Recent Posts

- Blackboard Upgrade – January 2026

- Spotlight on Excellence: Bringing AI Conversations into Management Learning

- Blackboard Upgrade – December 2025

- Preparing for your Physiotherapy Apprenticeship Programme (PREP-PAP) by Fiona Barrett and Anna Smith

- Blackboard Upgrade – November 2025

- Fix Your Content Day 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – October 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – September 2025

- The potential student benefits of staying engaged with learning and teaching material

- LearnTech Symposium 2025

Tags

ABL Practitioner Stories Academic Skills Accessibility Active Blended Learning (ABL) ADE AI Artificial Intelligence Assessment Design Assessment Tools Blackboard Blackboard Learn Blackboard Upgrade Blended Learning Blogs CAIeRO Collaborate Collaboration Distance Learning Feedback FHES Flipped Learning iNorthampton iPad Kaltura Learner Experience MALT Mobile Newsletter NILE NILE Ultra Outside the box Panopto Presentations Quality Reflection SHED Submitting and Grading Electronically (SaGE) Turnitin Ultra Ultra Upgrade Update Updates Video Waterside XerteArchives

Site Admin