Most university lecturers will have their favourite anti-lecturing quote. Mine has always been Camus’ oft-quoted “Some people talk in their sleep. Lecturers talk while other people sleep”. Another favourite is the variously attributed definition “Lecture: a process by which the notes of the professor become the notes of the student, without passing through the minds of either.”

In fairness to university lecturers, none of the lecturers I know deliver these kind of dreary monologues. Also, if a lecturer is timetabled into a room with a lectern, projector and screen, and tiered seating containing 250 students then surely we cannot chastise them for using that room for the purpose it was designed and intended for. Obviously such space can be subverted and used differently (as professors such as Eric Mazur and Simon Lancaster have done), but surely the best solution is simply not to build these kinds of spaces in the first place. If active, participatory learning in small groups is what is best (and the evidence suggests that it is) then why not build spaces that accommodate this kind of learning and teaching.

At the University of Northampton that’s exactly what is happening. As was recently reported in the Sunday Times, the University of Northampton’s Waterside campus “is to be built with no traditional lecture theatres, providing further evidence that the days of professors imparting knowledge to hundreds of students at once may be numbered.” The new campus “is the first in the UK to be designed without large auditoriums.”

While it is true that the majority of teaching that takes place at the Waterside campus is planned to be active, interactive and participatory, and to take place in small classes, there will obviously need to be some element of professors imparting knowledge to their students. This is, after all, for most people a key part of the process of teaching and learning. However, the plan for Waterside is for such ‘professorial knowledge imparting’ to take place online, prior to attending class; a process often known as flipped or blended learning. This means that time is not taken up in the small class sessions with getting knowledge across to the students, or with ‘covering content’, but on helping students to understand, assimilate and make sense of the knowledge they have grappled with prior to attending class.

Professor Nick Petford, Vice Chancellor of the University of Northampton, is not only building a campus in which active, participatory, small class teaching will be the norm, but as a member of the teaching staff he is already teaching in this way himself. Professor Petford adopted this blended learning approach in his physical volcanology classes during the 2015/16 academic year, and you can see him talking about how it went in this video.

At the end of the second day of CAIeRO, we hope you will feel like you’ve achieved a lot! But we know from experience that you will probably also feel like you have a lot still to do. This is why the last two stages of the CAIeRO process are important.

Action planning

While all your ideas are fresh in your minds (and ideally while all your team are still together in the room), it’s a good idea to agree on an action plan for the work you didn’t manage to do during the CAIeRO. This might include completing the learning activities for the modules you’ve been working on, reviewing and aligning other modules on the programme, completing quality assurance processes such as change of approval, and further training or development for you and your team. If you have a deadline to complete the work, like a planned start date for a new course or module, start from there and work backwards to determine when you need to complete each step. It’s important to lay out all the steps you need to take, and to put dates and names against them so that you don’t lose momentum. Identify ‘owners’ for each task but also anyone who can help – there will always be other work to do, but shared deadlines can help to make sure you fit in what you’ve agreed to do.

While all your ideas are fresh in your minds (and ideally while all your team are still together in the room), it’s a good idea to agree on an action plan for the work you didn’t manage to do during the CAIeRO. This might include completing the learning activities for the modules you’ve been working on, reviewing and aligning other modules on the programme, completing quality assurance processes such as change of approval, and further training or development for you and your team. If you have a deadline to complete the work, like a planned start date for a new course or module, start from there and work backwards to determine when you need to complete each step. It’s important to lay out all the steps you need to take, and to put dates and names against them so that you don’t lose momentum. Identify ‘owners’ for each task but also anyone who can help – there will always be other work to do, but shared deadlines can help to make sure you fit in what you’ve agreed to do.

At this point, while you have diaries to hand, you should schedule a follow up meeting to review progress. This will allow you to keep each other on track and keep the modules closely aligned, and it will also allow you to adjust if any changes come up in the meantime. Remember your Learning Designer and Learning Technologist are there to help you throughout the whole journey of design into delivery, and they will be keen to get feedback on what has (and has not) worked well for you and your team, as well as what works well with the students when you start to deliver the module(s). This helps us to get a clear idea of how much work is still to be done, and to schedule support accordingly, but also to shape our support and guidance for future CAIeROs.

Reflecting on CAIeRO

We hope that the CAIeRO process will help you build your course design skills, as well as building a better module. At each stage of the CAIeRO, your learning designer will try to make explicit the principles informing each task, and help you think about how to transfer the work you’re doing to other areas. If you have time at the end of the CAIeRO workshop, you might allow 15 minutes or so for reflection, and try to capture the discussions you’ve had and the reasons behind the changes and choices you’ve made. This will not only be useful when you come to deliver the module, but also when you are thinking about your own professional development as an educator.

We’d love to hear your reflections on the CAIeRO process, and any feedback that might help us improve. If you’d like to tell us about it, drop us an email at LD@northampton.ac.uk.

This is one in a series of posts about the CAIeRO process. To see the full list, go the original post: De-mystifying the CAIeRO.

Need a CAIeRO? Email the Learning Design team at LD@northampton.ac.uk.

Stage 3 of the CAIeRO process usually begins at the start of the second day. By this stage you should have your blueprint and storyboard finalised, and a clear vision of your new module design(s). The next step is to start making your ideas more concrete, by creating the learning and teaching activities that will support students to reach the learning outcomes.

On your storyboard, you will have a number of placeholders along the learning journey where students need to learn particular things. Pick one of these to start with, and think about what kind of learning activities might help the students to get to grips with it. Is it a new concept or skill, where they will need some initial information or a demonstration from you (or someone else) to get started? Is it a complex idea or skill they will need some time to explore? Is there an opportunity to let them apply it, through experimentation or practice? Is it an area where they might benefit from sharing knowledge or experience, or being exposed to different perspectives through debate? You might find the Hybrid Learning Model cards helpful here, as they list verbs describing what the tutor and the student can do to support different types of learning.

On your storyboard, you will have a number of placeholders along the learning journey where students need to learn particular things. Pick one of these to start with, and think about what kind of learning activities might help the students to get to grips with it. Is it a new concept or skill, where they will need some initial information or a demonstration from you (or someone else) to get started? Is it a complex idea or skill they will need some time to explore? Is there an opportunity to let them apply it, through experimentation or practice? Is it an area where they might benefit from sharing knowledge or experience, or being exposed to different perspectives through debate? You might find the Hybrid Learning Model cards helpful here, as they list verbs describing what the tutor and the student can do to support different types of learning.

Creating learning activities

This section of the workshop is sometimes thought of as the ‘e-tivity bit’, but it’s important not to think too much about the technology to start with. Think about the type of activity you think would work best. If you or your colleagues have taught that subject before, what worked well? Once you know what you’d like the students to be doing, then think about the context – is this something that needs to happen in the classroom or outside? Technology can add possibilities and allow us to design learning experiences that weren’t possible in the past – think about linking up live with an expert in the field, or providing your students with world-class open educational resources. It’s also important to make sure that your students are exposed to digital learning practices, and develop the skills they will need to keep learning beyond their degree. But online is not always the best mode for every activity, so if you have face to face time with your students, make sure you use it wisely!

To help you figure out the best context for each activity, it’s important to be aware of the strengths and weaknesses of the tools available to you. Your Learning Technologist can help you with this, and you may also be able to get advice from your colleagues on their experiences. Don’t be afraid to talk about things that haven’t worked well – it may be that there are new tools or skills that could help you tweak that activity so that it works better next time, and part of the aim of the CAIeRO is to develop your skills as well as your module!

This is why we will ask you to create at least one online learning activity in the learning environment (NILE) as part of the workshop. You can take advantage of all the skills in the room, and you’ll leave with something real that you can use in your teaching! If you wish, you can use the e-tivity template, which embeds some key principles for online learning activities, including having a clear purpose, active learning tasks and opportunities for reflection and feedback. Or if you prefer, you can design your own.The reality check

Once you have some learning activities created in NILE, it’s time to take a break while your reality checkers look them over. Reality checkers will ideally be students, but can also be colleagues, externals, anyone who has not been involved in the design of the module so far. Remember too that they don’t have to be in the room, they just need to be able to access the learning environment! The purpose of this stage of the workshop is to get an objective view of what you have created, and to provide constructive feedback to help you improve it. It’s important that you resist the urge to ‘help’ or ‘explain’ things to your reality checkers – remember when your real students come to this activity, they may not be able to call you and ask for clarification! Ideally your activity should stand by itself, with clear instructions allowing anyone who hasn’t seen it before to understand the purpose and how to complete it.

Once you have some learning activities created in NILE, it’s time to take a break while your reality checkers look them over. Reality checkers will ideally be students, but can also be colleagues, externals, anyone who has not been involved in the design of the module so far. Remember too that they don’t have to be in the room, they just need to be able to access the learning environment! The purpose of this stage of the workshop is to get an objective view of what you have created, and to provide constructive feedback to help you improve it. It’s important that you resist the urge to ‘help’ or ‘explain’ things to your reality checkers – remember when your real students come to this activity, they may not be able to call you and ask for clarification! Ideally your activity should stand by itself, with clear instructions allowing anyone who hasn’t seen it before to understand the purpose and how to complete it.

Your reality checkers will complete a feedback form that you can refer back to afterwards. You may also want to ask them to run through their thoughts on the activities, to get some more detail (if they are not in the room you could do this using Collaborate or Skype).

Review and adjust

Once your reality checkers have left, it’s a good idea to take a short amount of time to do some adjustments based on their feedback, while it’s fresh in your mind. Then you’re almost done!

This is one in a series of posts about the CAIeRO process. To see the full list, go the original post: De-mystifying the CAIeRO.

Need a CAIeRO? Email the Learning Design team at LD@northampton.ac.uk.

Jane Mills, Senior Lecturer for Fashion at the University of Northampton and BA (Hons) Fashion, Textiles for Fashion, and Footwear and Accessories students, Bregha, Gemma, Louise and Upasna discuss their use of the Trello App to support their group work projects.

[Posted on behalf of Elizabeth Palmer]

When starting to make online activities for blended learning there is a temptation to take content that is currently being delivered face-to-face in lectures (through software such as Powerpoint) and moving that content into an online format where the students are ‘digitally page turning’ through material: read or watch x, y and z before class.

The learning and teaching plan for blended learning is that we are creating interactive activities that support students towards developing their own knowledge, understanding and creating outputs that can then be used in class. In other words we are trying to flip the focus away from tutor created content that the student must passively absorb, to student-led interactive and created content.

Any content provided to students should be done in an interactive, discovery based way i.e. rather than telling them the answer we allow them to discover the answer through questioning, testing, trialling, problem solving etc. online and then reinforce and develop this face to face. If you are trying out e-tivities for the first time Xerte can be a useful package to start this process. Have a look at these two examples of using Xerte to make interactive activities on academic skills: here and here. Whilst they are not necessarily perfect, they demonstrate how you can use Xerte’s functionality to create knowledge checking, interactive exercises that you could then build on in class or use as a basis for students to undertake a more complex task.

The following presentation by Dr. Rachel Maunder entitled “Watering down Waterside” provides a summary of a similar presentation delivered at the School of Social Sciences Learning and Teaching event in February 2016.

Incorporating the Institute of Learning and Teaching’s (ILT) Direction of Travel video, the presentation provides advice and strategies for programme teams when thinking about the design of their modules and programmes for delivery now, and in preparation for Waterside, linking the use of NILE and the NILE benchmarks, describing blended learning and flipped learning approaches (with examples such as the module PSY1006 – Becoming a Psychologist), and introducing elements of the CAIeRO process.

The honest answer to this question is, ‘it depends’. A good NILE site will de different depending on your subject, mode of delivery, level of delivery, and various other factors. As you’d expect, as much as possible we like to avoid the idea that a one-size-fits-all approach is possible to learning design. However, what is sometimes useful when trying to come up with ideas for things to do in NILE is to look at what other people have been doing. To make this easier, we have collected together a few sites which we feel are quite interesting, and have made them available as self-enrol (and self-unenrol) NILE organisations.

The honest answer to this question is, ‘it depends’. A good NILE site will de different depending on your subject, mode of delivery, level of delivery, and various other factors. As you’d expect, as much as possible we like to avoid the idea that a one-size-fits-all approach is possible to learning design. However, what is sometimes useful when trying to come up with ideas for things to do in NILE is to look at what other people have been doing. To make this easier, we have collected together a few sites which we feel are quite interesting, and have made them available as self-enrol (and self-unenrol) NILE organisations.

If you’d like to have a look at any of these sites, just do the following:

1. Log in to NILE

2. Click on the ‘Sites and Organisations’ tab

3. Search in the ‘Organisation Search’ box for either, LTC, SSAS, PSAS, CRIT101

4. Enrol on the site

Currently there are four NILE sites available as self-enrol organisations. These are:

• Let’s Teach Computing (LTC)

• Study Skills for Academic Success (SSAS)

• Postgraduate Skills for Academic Success (PSAS)

• Critical Thinking – A Practical Introduction (CRIT101)

If you’ve got a good NILE site and would like to make it available as a self-enrol organisation please get in touch with us at: LD@northampton.ac.uk

And finally, if you think that you’ve got a great NILE site, you might like to enter it for a Blackboard Exemplary Course Award: http://blackboard.com/ecp

Bob has always taught his module using a traditional lecture-seminar format. He wants to bring in some new ideas, but doesn’t have much time to read up on pedagogic research. In the CAIeRO, he is teamed up with Joe and Laura. Joe is a new member of staff from a distance learning institution, who uses a lot of open educational resources to support his students in independent study. Laura leads another module on the programme, where she has been trialling peer teaching and problem based approaches. They spend some time discussing, sharing and planning. At the end of the session Bob’s storyboard for the module looks very different…*

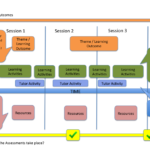

In the context of CAIeRO, a ‘storyboard’ is a visual plan of your module from beginning to end. Once you have the blueprint of the module agreed, the next step is to figure out how to deliver that in practice. This is sometimes the most challenging part of the CAIeRO process, but it can also be where the magic happens – where a new vision for the module starts to become a reality.

The main aims of the storyboarding task are around sequencing, alignment and coherence. These can be achieved through mapping out the themes, learning activities and assessment items – what students need to know, how they will learn it, and how they will show that they have learned it (that constructive alignment idea again!). The idea is to create a logical sequence of activity, or learning journey, that allows the learner to build knowledge, skills and understanding so that these can be demonstrated through assessment. We’ll then go on to consider in detail how that learning might happen, and what kinds of activities can be put in place to support it.

You will be asked to note down all of the broad themes that students on the module will need to learn about – the big concepts, the core skills, everything they’ll need to learn to reach the outcomes you’ve written – and to put them in some sort of sequence. This is a fun activity involving lots of post-it notes and flip chart paper, allowing things to be moved around and re-arranged as needed. The trick with storyboarding is to approach it from the perspective of the learner. Resist the temptation to replicate the way you deliver the module now – in week 1 I do this, in week 2 I do this… Instead, ask yourself: if I were a student coming to this for the first time, what would I need to learn first?

You will be asked to note down all of the broad themes that students on the module will need to learn about – the big concepts, the core skills, everything they’ll need to learn to reach the outcomes you’ve written – and to put them in some sort of sequence. This is a fun activity involving lots of post-it notes and flip chart paper, allowing things to be moved around and re-arranged as needed. The trick with storyboarding is to approach it from the perspective of the learner. Resist the temptation to replicate the way you deliver the module now – in week 1 I do this, in week 2 I do this… Instead, ask yourself: if I were a student coming to this for the first time, what would I need to learn first?

Start adding your post-its to the timeline – they need to learn about this, they need to learn how to do that – start with broad headings, and then break these down in to more detailed subheadings (these will be your learning activities). While you’re doing this, it’s also helpful to note down any relevant learning resources you have created or found (texts, videos, even expert speakers!). We’ll need these in the next section of the workshop. You might find you have more learning activities specified for introductory level 4 modules, where students might benefit from having more structure, and less for modules that are more student-led or involve more independent study. That’s fine, but if you’re unsure, you can do a quick ‘sense check’ back to your look and feel cards. Did you specify how much guidance you thought was appropriate? Are you sticking to that, or has your thinking changed?

Once you have a rough sequence for the learning activities, place your summative assessment activities on the timeline (usually using a different colour post-it). Here are some more ‘sense checks’. Are you covering all of the knowledge and skills needed for that assessment before it happens? If not, you need to move things around – or reconsider what’s being assessed at that point. Don’t worry if your blueprint changes as a result of storyboarding. CAIeRO is a dynamic process and nothing is set in stone! You should also check at this point that your learning activities plan includes opportunities to learn the skills required for the assessment, and to try these out formatively.

At this point you should be starting to get a sense of how the workload looks. Some areas of learning will be bigger than others. Some will cross over, and you may need to move things around. At this point there are two ‘sense checks’ to do. The first is around workload for the learner. Can you space out the activities evenly so that the workload is balanced? Do you know what’s happening in other modules that run alongside this? Think about how the student will experience the plan you are putting in place. This leads in to the second sense check: Where on the timeline will the students most need access to you?There is no right answer to this question; it will vary according to the subject, level and cohort, and you will also have to consider the constraints of your own workload, timetabling and so on. The important thing is to plan contact time that will have the most impact for learning. You might have one aspect of the module that students find particularly difficult, and choose to spend a substantial amount of contact time at that point to make sure students can progress. You might have the first module in the first year of a programme, and decide that weekly clarification sessions are important to make sure students are on track. You might have a distance cohort on different time zones, and decide that the best support you can provide is in frequent monitoring of discussions or online ‘office hours’ sessions. Whatever you decide, the CAIeRO process will help you work through the options – and the final storyboard can be digitised as a useful visual to help students understand your chosen approach.

If you’re doing a standard two day CAIeRO, ideally you will have a (mostly) completed storyboard for your module by the end of day 1. It’s a good idea to pause and reflect at this point, but it’s also important not to lose momentum. Once your outline is finalised, the next step is to start creating the learning activities.

This is one in a series of posts about the CAIeRO process. To see the full list, go the original post: De-mystifying the CAIeRO.

Need a CAIeRO? Email the Learning Design team at LD@northampton.ac.uk.

*All characters are fictional representations. ‘Bob’ and ‘Laura’ were inspired by Alex Bruton’s post on the Flipped Academic – worth a read if you have a little more time to spare…

Yes, they probably will. A recent study conducted at Queen’s University Belfast reported that students are more likely to view the availability of recorded lectures as a reinforcement of class teaching, rather than a replacement of it.

In a post-course survey, 96 per cent of students said that the availability of footage had had no impact on their attendance … [and] 98 per cent of students said that revision in preparation for an exam was a primary reason for viewing a video.

A brief summary of the research published in the THES is available here.

This is a fairly long blog post, so in case you don’t have time to read it all, the key message is this:

Flipping the classroom is likely to lead to improvements in student performance and reduced failure rates when it is used as part of an overall strategy to create a more active learning environment. These gains are likely to have the greatest impact in classes with less than fifty students.

"Education is not an affair of 'telling' and being told, but an active and constructive process." John Dewey, Democracy and Education, 1916

One important question arising from our earlier blog posts, ‘What is the flipped classroom?’ and, ‘Designing a flipped module in NILE’, is whether or not flipping your class will improve student learning. Clearly there must be some evidence to support a flipped approach to teaching and learning, otherwise we wouldn’t be suggesting it, but what is that evidence, and where is it?

At the risk of appearing to concede defeat before we’ve even begun, I would like to start by looking at a recent paper which argues that flipping the classroom does not guarantee any gains in student achievement.

Flipping the classroom is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition to generate improvements in learning

‘Improvements from a Flipped Classroom May Simply Be the Fruits of Active Learning’ is a very interesting paper by Jensen, et al (2015), and it is clear from the title what their findings are. They begin the paper by stating one of the main problems behind many of the claims that the flipped classroom improves student learning, which is that there are normally too many variables that have changed between the flipped and the non-flipped classroom to isolate flipping as the key variable. They note that flipping the classroom usually leads to more active learning taking place (indeed, this is often the reason that teachers want to flip the classroom in the first place), and they investigated the extent to which the increase in the amount of active learning, not flipping, is the key variable.

Jensen, et al (2015) took a class of 108 students and divided them into two groups, one of 53 and one of 55. One group had a flipped experience, the other a non-flipped experience – however, both sessions were very active. The diagram on the left indicates how the sessions worked. The flipped and non-flipped classes were compared with each other, and also with the previous year’s class of 94 students, referred to as the original class. While the content and the underlying structure of the teaching remained consistent, a great deal of time and effort was put into creating additional materials for the flipped and non-flipped classes, which is evident from reading the paper.

As will be clear from the title of the paper, the flipped classroom did not produce statistically significant learning gains or improvements in attitudes to learning over the non-flipped classroom, and neither the flipped nor the non-flipped classroom significantly outperformed the original class. The one area in which the flipped classroom did produce a statistically significant improvement was in final examination scores of low level items (e.g., remember and understand type questions) over the original class.

Regarding these results I think that it is important to make at least two observations. Firstly, it should be borne in mind that the students in the study were high ability, highly motivated students attending a private university at which the average ACT score of students is 28 and average GPA is 3.82. For context, an ACT score of 28 would put a student in the top 10% and a GPA of 3.82 would be between an A- and an A. Whilst not necessarily Oxbridge students, they are solid Russell Group students, the kind of students who “virtually teach themselves; they do not need much help from us” (Biggs and Tang, 2011, p.5). Secondly, the original class appears to have been be a fairly active class already, certainly if judged by the standards set in the definition by Freeman, et al (2014) which we will look at later.

The study by Jensen, et al., did come up with other interesting findings though. One finding (2015, p.8 and p.10) which reinforces the importance of time spent with lecturers was that,

Students “perceived their time with the instructor as more influential for learning, regardless of whether they were participating in” the flipped class or in the non-flipped class … “the presence of the instructor and/or peer interaction had a greater influence on students’ perceptions of learning than the activities themselves.”

Additionally, Jensen, et al., were not dismissive of the potentials and advantages of the flipped classroom, noting (2015, p.10) that,

“If active learning is not currently being used or is being used very rarely, the flipped classroom may be a viable way to facilitate the use of such approaches, if the costs of implementation are not too great. As the research indicates, using active learning in the flipped approach can increase student learning as well as student satisfaction over traditional, non-active learning approaches.”

The claim made by Jensen, et al., that active learning is the key variable is certainly very credible, and, as we shall see, it is increasingly apparent in recent publications that flipping the classroom is a very popular way of creating a more active learning environment.

Flipping the classroom is a good way of making classrooms more active

‘The Flipped Classroom of Operations Management: A Not-For-Cost-Reduction Platform’ is a 2015 paper by Asef-Vaziri, and it provides an excellent introduction to the flipped classroom. Additionally, the literature review in the paper gives a good overview of some recent publications on the subject. A wide variety of active learning ideas are discussed in the paper (pp.74-80) and they give a good insight into the practical workings of Asef-Vaziri’s flipped classroom. Right from the outset Asef-Vaziri (2015, p.72) makes it clear that the benefits of using the flipped classroom are because it allows more class time to be spent engaged in active learning:

“Class time is no longer spent teaching basic concepts, but rather on more value-added activities, such as problem solving, answering questions, systems thinking, and potentially on collaborative exercises such as case studies, Web based simulation games, and real-world applications”

Asef-Vaziri’s classes were fully flipped in the autumn of 2012 (141 students) and 2013 (157 students), and the average grades were compared to those of the classes in the spring and autumn of 2011 (both with 160 students) which not flipped. The results were as follows:

| Autumn 2012 flipped classroom |

Autumn 2013 flipped classroom |

|

| Average grade increase over spring 2011 traditionally taught class |

+7.4% | +7.3% |

| Average grade increase over autumn 2011 traditionally taught class |

+11.8% | +11.6% |

The improvements in Asef-Vaziri’s students’ grades are undoubtedly impressive, and these high gains are likely to result from the significant amount of time and effort that Asef-Vaziri put into re-designing the course.

What came across very clearly in Asef-Vaziri’s paper is the idea that the flipped classroom offers ‘the best of both worlds’, creating increased opportunity to engage in active learning in ways that are difficult for the traditional classroom (due to lack of time) and difficult for online classes (due to lack of face-to-face interactions).

A cursory glance at a number of other recent publications about the flipped classroom makes it clear that a key motivation for using it has been in order to create more active learning opportunities. For example, in their paper, ‘Moving from Flipcharts to the Flipped Classroom: Using Technology Driven Teaching Methods to Promote Active Learning in Foundation and Advanced Masters Social Work Courses’, Holmes, et al (2015) state that the desire to engage in more active learning was the primary driver behind introducing the flipped classroom.

A number of other papers bear out the notion that flipping the classroom is a popular way of adopting a more active approach to teaching and learning, including: Gilboy, et al (2014); Hung (2015); Love, et al (2013); Roach (2104); See and Conry (2014); Simpson and Richards (2015); and Tune, et al (2013). All of these papers make the connection between the flipped classroom and increasingly active approaches to teaching and learning.

Hopefully the above discussion goes some way to making the case that the flipped classroom is a good (or, at least, a popular) way of creating a more active classroom. We will now look at some more evidence in support of the idea that adopting an active approach to teaching and learning is likely to improve student performance.

Active learning increases student performance

Active learning is certainly not a new idea. John Dewey (1902, p.6) knew that learning is an active process, and referred to it as such since the beginning of the last century. Some years later, 112 to be exact, Freeman, et al (2014) published an important meta-analysis of STEM education in which 158 active learning classes were compared with 67 traditionally taught classes. Aleszu Bajak, writing in the daily news site of the journal ‘Science’, summarised the paper as follows: ‘Lectures Aren’t Just Boring, They’re Ineffective, Too, Study Finds’. And Eric Mazur, cited in Bajak (2014), said

“This is a really important article—the impression I get is that it’s almost unethical to be lecturing if you have this data.”

The results of the paper “indicate that average examination scores improved by about 6% in active learning sections, and that students in classes with traditional lecturing were 1.5 times more likely to fail than were students in classes with active learning.” (Freeman, et al, 2014, p.8410) To get a sense of the significance of the results, the authors note (p.8413) that had it been a medical randomised control trial it may have been stopped early because of the clear benefit of the intervention being tested; in this case, the active learning. The authors also note that because the retention of students on active learning courses is higher, and because it is lower ability learners who typically drop-out, the positive effects of active learning could actually be greater than reported because the active learning classes were holding on to a higher proportion of their lower ability learners than the traditional classes. And, good news for Waterside, active learning was shown to have “the highest impact on courses with 50 or fewer students.” (p.8411)

One issue which may be useful is to define what is meant by active learning. For the purposes of their study, Freeman, et al (2014, p.8413-4) adopted the following definition:

“Active learning engages students in the process of learning through activities and/or discussion in class, as opposed to passively listening to an expert. It emphasises higher-order thinking and often involves group work.”

Freeman, et al (2014, p.8410) state that for the purposes of their study the “active learning interventions varied widely in intensity and implementation, and included approaches as diverse as occasional group problem-solving, worksheets or tutorials completed during class, use of personal response systems [clickers] with or without peer instruction, and studio or workshop course designs.”

Other studies about the effectiveness of adopting a more active approach to teaching and learning in STEM subjects include Hake’s 1998 paper ‘Interactive-engagement vs traditional methods: A six-thousand student survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics courses.’ The paper concludes that:

“Comparison of IE [interactive engagement] and traditional courses implies that IE methods enhance problem-solving ability. The conceptual and problem-solving test results strongly suggest that the use of IE strategies can increase mechanics-course effectiveness well beyond that obtained with traditional methods.”

Also of interest is ‘Peer Instruction: Ten years of experience and results’ in which Crouch and Mazur (2001) discuss the positive effects of replacing a more traditional approach to physics teaching with Mazur’s method of peer instruction, an approach to teaching and learning developed in the 1990s which inspired the flipped classroom movement.

Whilst a good deal of the most rigorous and credible quantitative studies into active learning have been carried out in STEM subjects, Hung (2015) makes the point in the paper ‘Flipping the classroom for English language learners to foster active learning’, that,

“it is evident that although the flipped classroom approach has mainly been conducted in STEM fields, its feasibility across disciplines (in this case, language education) should not be underestimated.”

Conclusion

It’s important to make clear that this has not been an extensive, rigorous and systematic study of every recent publication on the flipped classroom, so any conclusions drawn must take that into account. Nevertheless, and with this in mind, I think that we can still draw a few conclusions with certainty, and a few more with slightly less certainty.

We can be very confident that:

- Active learning produces statistically significant improvements in student achievement in science, engineering and mathematics.

- Active learning in classrooms of under 50 students produces the largest gains.

- Even a small amount of active learning will produce positive gains in student achievement.

We can be reasonably confident that:

- The positive effects of active learning seen in science, engineering and mathematics will be applicable to other subject areas.

- Lecturers in a variety of subject areas have successfully flipped their classrooms.

- The gains in students’ learning achieved by the flipped classroom are more likely to be a result of increasing the amount of active learning taking place online and/or in the classroom.

- Flipping the classroom is a good way of creating a more active learning environment.

It may be the case that:

- The gains in student achievement produced by flipping the classroom will have a greater effect in non-Russell Group universities.

- Flipping the classroom will have a greater effect when focused at the level of knowledge, understanding and application rather than analysis, synthesis and evaluation.

From the papers looked at, it is not clear:

- Whether there are significant differences in the effectiveness of different types of flipped/active learning opportunities.

- Whether there is an optimal level of student activity online and in the classroom (i.e., is more always better?)

- Whether students from all cultural backgrounds experience similar improvements in performance from the flipped/active classroom.

- Whether students whose first language is not the language in which the course is taught experience additional benefits or disbenefits from flipped/active classroom.

Readers wanting to look at the literature themselves and draw their own conclusions are directed to the further reading section at the end of this blog post, which provides links to many recent papers on the flipped classroom from a diverse range of subject areas.

References

Asef-Vaziri, A. (2015) The Flipped Classroom of Operations: A Not-For-Cost-Reduction Platform. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education. 13(1), pp.71-89.

Bajak, A. (2014) ‘Lectures Aren’t Just Boring, They’re Ineffective, Too, Study Finds’ Science News. 12th May.

Biggs, J. and Tang, C. (2011) Teaching for Quality Learning at University, 4th Edition. Berkshire: Open University Press.

Dewey, J. (1902) The Child and the Curriculum. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p.9.

Crouch, C. and Mazur, E. (2001) Peer Instruction: Ten years of experience and results. American Journal of Physics. 69(9), pp.970-977.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S., McDonough, M., Smith, M., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H. and Wenderoth, M. (2014) Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering and mathematics. PNAS. 111(23), pp.8410-8415.

Gilboy, M., Heinerichs, S. and Pazzaglia, G. (2015) Enhancing Student Engagement Using the Flipped Classroom. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 47(1), pp.109-114.

Hake, R. (1998) Interactive-engagement versus traditional methods: A six-thousand-student survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics courses. American Journal of Physics. 66(1), pp.64-74.

Holmes, M., Tracey, E., Painter, L., Oestreich, T. and Park, H. (2015) Moving from Flipcharts to the Flipped Classroom: Using Technology Driven Teaching Methods to Promote Active Learning in Foundation and Advanced Masters Social Work Courses. Clinical Social Work Journal.43(2), pp.215-224.

Hung, H-T. (2015) Flipping the classroom for English language learners to foster active learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning. 28(1), pp.81-96.

Jensen, J., Kummer, T.. and Godoy, P. (2015) Improvements from a Flipped Classroom May Simply Be the Fruits of Active Learning. CBE – Life Sciences Education. 14(1), pp.1-12.

Love, B., Hodge, A., Grandgenett, N. and Swift, A. (2014) Student learning and perceptions in a flipped linear algebra course. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology. 45(3), pp.317-324.

Roach, T (2014) Student perceptions toward flipped learning: New methods to increase interaction and active learning in economics. International Review of Economics Education. 17, pp.74-84.

See, S. and Conry, J. (2014) Flip My Class! A faculty development demonstration of a flipped-classroom. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. 6(4), pp.585-588.

Simpson, V. and Richards, E. (2015) Flipping the classroom to teach population health: Increasing the relevance. Nurse Education in Practice.15(3), pp.162-167.

Tune, J., Sturek, M. and Basile, D. (2013) Flipped classroom model improves graduate student performance in cardiovascular, respiratory, and renal physiology. Advances in Physiology Education. 37(4), pp.316-320.

Further reading about the flipped classroom

Asef-Vaziri, A. (2015) The Flipped Classroom of Operations: A Not-For-Cost-Reduction Platform. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education. 13(1), pp.71-89.

Bristol, T. (2014) Flipping the Classroom. Teaching and Learning in Nursing. 9(1), pp.43-46.

Brunsell, E. and Horejsi, M. (2013) A Flipped Classroom in Action. The Science Teacher. 80(2), p.8.

Chen, Y., Wang. Y., Kinshuk, and Chen, N-S. (2014) Is FLIP enough? Or should we use the FLIPPED model instead? Computers & Education. 79, pp.16-27.

Enfield, J. (2013) Looking at the Impact of the Flipped Classroom Model of Instruction on Undergraduate Multimedia Students at CSUN. TechTrends. 57(6), pp.14-27.

Forsey, M., Low, M. and Glance, D. (2013) Flipping the sociology classroom: Towards a practice of online pedagogy. Journal of Sociology. 49(4), pp.471-485.

Gilboy, M., Heinerichs, S. and Pazzaglia, G. (2015) Enhancing Student Engagement Using the Flipped Classroom. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 47(1), pp.109-114.

Herreid, C. amd Schiller, N. (2013) Case Studies and the Flipped Classroom. Journal of College Science Teaching. 42(5), pp.62-66

Holmes, M., Tracey, E., Painter, L., Oestreich, T. and Park, H. (2015) Moving from Flipcharts to the Flipped Classroom: Using Technology Driven Teaching Methods to Promote Active Learning in Foundation and Advanced Masters Social Work Courses. Clinical Social Work Journal. 43(2), pp.215-224.

Hung, H-T. (2015) Flipping the classroom for English language learners to foster active learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning. 28(1), pp.81-96.

Jacot, M., Noren, J. and Berge, Z. (2014) The Flipped Classroom in Training and Development: Fad or the Future? Performance Improvement. 53(9), pp.23-28.

Jensen, J., Kummer, T.. and Godoy, P. (2015) Improvements from a Flipped Classroom May Simply Be the Fruits of Active Learning. CBE – Life Sciences Education. 14(1), pp.1-12.

Kim, M., Kim, S., Khera, O. and Getman, J. (2014) The experience of three flipped classrooms in an urban university: an exploration of design principles. The Internet and Higher Education. 22, pp.37-50.

Love, B., Hodge, A., Grandgenett, N. and Swift, A. (2014) Student learning and perceptions in a flipped linear algebra course. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology. 45(3), pp.317-324.

Lujan, H. and DiCarlo, S. (2014) The flipped exam: creating an environment in which students discover for themselves the concepts and principles we want them to learn. Advances in Physiology Education. 38(4), pp.339-342.

Roach, T (2014) Student perceptions toward flipped learning: New methods to increase interaction and active learning in economics. International Review of Economics Education. 17, pp.74-84.

See, S. and Conry, J. (2014) Flip My Class! A faculty development demonstration of a flipped-classroom. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. 6(4), pp.585-588.

Simpson, V. and Richards, E. (2015) Flipping the classroom to teach population health: Increasing the relevance. Nurse Education in Practice. 15(3), pp.162-167.

Slomanson, W. (2014) Blended Learning: A Flipped Classroom Experiment. Journal of Legal Education. 64(1), pp.93-102.

Tune, J., Sturek, M. and Basile, D. (2013) Flipped classroom model improves graduate student performance in cardiovascular, respiratory, and renal physiology. Advances in Physiology Education. 37(4), pp.316-320.

Recent Posts

- NILE Ultra Course Award Winners 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – June 2025

- Learning Technology / NILE Community Group

- Blackboard Upgrade – May 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – April 2025

- NILE Ultra Course Awards 2025 – Nominations are open!

- Blackboard Upgrade – March 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – February 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – January 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – December 2024

Tags

ABL Practitioner Stories Academic Skills Accessibility Active Blended Learning (ABL) ADE AI Artificial Intelligence Assessment Design Assessment Tools Blackboard Blackboard Learn Blackboard Upgrade Blended Learning Blogs CAIeRO Collaborate Collaboration Distance Learning Feedback FHES Flipped Learning iNorthampton iPad Kaltura Learner Experience MALT Mobile Newsletter NILE NILE Ultra Outside the box Panopto Presentations Quality Reflection SHED Submitting and Grading Electronically (SaGE) Turnitin Ultra Ultra Upgrade Update Updates Video Waterside XerteArchives

Site Admin