Authors: Elizabeth Palmer, (University of Northampton, Learning Designer,) Sylvie Lomer, (University of Manchester, Lecturer in Education) and Ivelina Bashliyska (3rd Year Undergraduate Student and Assistant Researcher).

With thanks to Nadine Shambrooke and David Cousens for support with transcription and coding.

______________________________________________________________________

The University of Northampton has taken an institutional approach to learning and teaching through the widespread adoption of Active Blended Learning (ABL) as its new ‘normal’. To find out more please visit: https://www.northampton.ac.uk/ilt/current-projects/waterside-readiness/

However, student engagement has been highly variable, which has created a number of challenges for staff. Semi-structured qualitative focus groups have been undertaken with 201 undergraduate students across all the year groups and faculties during the academic year 16/17 based on a pilot study of 24 students in academic year 15/16. These focus groups have been looking at trying to uncover the students own perceptions and experiences of ABL in order to unpick the reasons behind varying patterns and engagements and to glean student insight into the factors that inhibit or encourage engagement with ABL.

The study has revealed a number of key factors which students identify as having significant impact on their engagement. Key success factors include effective pedagogical design, in particular establishing a clear and explicit relationship between online and face to face components of modules, and scaffolding the development of digital skills and literacies in the process of establishing online tasks. A strong relationship between staff and students is also critical, where students trust in the decisions and motivations of staff. This is signalled by following up on online tasks, providing feedback where relevant, and explicitly discussing the value of online tasks to module learning outcomes and employability skills. A key finding is that students’ conceptions of learning, teaching & knowledge impact on their engagement with ABL, and are not necessarily compatible with ABL principles. These factors are complex, interdependent and have varying loci of control. Staff can take a number of measures to increase the likelihood of student engagement, although certain factors remain ultimately within the agency of students. Understanding these issues is critical to the success of ABL.

The following artefacts provide the results of the study to date:

Read the Interim Report from the Main Study here:

For Ten Top Tips on how to design ABL to maximise student engagement:

Read the Pilot Study Report here:

Summer is fast approaching and it’s business as usual in the the LearnTech Team. As this academic year draws to a close, we are already looking ahead and preparing for next year’s teaching. With this in mind, we will be offering our weekly LearnTech lunchtime sessions and other training opportunities on a rolling basis over the summer months, maximising the opportunities for you to engage, pick up new skills and receive the support you need to create inspiring and active teaching content for the benefit of your students. One tool in particular you may wish to familiarise yourself with is Turnitin’s new interface Feedback Studio, due for release from August.

LearnTech lunchtime sessions currently introduce some of our core NILE tools and some specific SaGE elements, including their potential applications and how these technologies can enhance your teaching and learning. Sessions are being offered at Park and we will happily offer parallel sessions at Avenue Campus on a request basis; please contact Vicky Brown, Learning Technology Manager in the first instance.

You can book now and come along to receive updates, refresh your skills and find out how your peers are working using UN-supported LearnTech tools. Feel free to bring along your own lunch to the hour long sessions.

We look forward to welcoming you over the coming weeks. Details, dates and booking links follow:

Kaltura/ MediaSpace (video)

As the University has now moved to a single video solution in Kaltura (MediaSpace), this is a chance for those who have already started to engage with this tool and those as yet to experience it. The following areas may cover an introduction to MediaSpace; video capture using CaptureSpace; uploading video to MediaSpace; embedding video content in NILE; using quizzes in Kaltura.

Monday 5 June – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Tuesday 4 July – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Tuesday 1 August – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Friday 1 September – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Tuesday 26 September – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Tuesday 24 October – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Tuesday 21 November – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Please sign up here: http://bit.ly/2fWkTbG

Collaborate (Virtual Classroom)

This session will introduce those new to using online virtual classrooms (Northampton is licensed for Collaborate: Ultra Experience until 2020) as well as for those who are curious to learn about new functionalities now available in the tool. Topics may cover some of the following: setting up the tool in your NILE sites; inviting attendees; sharing files/ applications/ the virtual whiteboard; running a virtual classroom session; moderating sessions; recording sessions; break-out rooms.

Monday 22 May – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, IT Training Room

Monday 19 June – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Tuesday 18 July – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Monday 14 August – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Monday 11 September – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Monday 9 October – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Monday 6 November – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Monday 4 December – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Please sign up here: http://bit.ly/2eG7mZR

MyPad / Edublogs (blogging tool)

MyPad (Edublogs) is the University’s personal and academic (WordPress) blogging tool and can be used in a number of ways to communicate and share learning resources. Topics covered may include: creation of individual / class student blogs; use of menus/ media; blog administration within modules; creation of class websites.

Friday 30 May – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Monday 26 June – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, IT Training Room

Monday 24 July – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Tuesday 22 August – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Monday 18 September – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Monday 16 October – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Tuesday 14 November – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Tuesday 12 December – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Please sign up here: http://bit.ly/2f4BEUM

Assessments (Rubrics)

Have you heard about the use of rubrics in NILE and wondering what all the fuss is about? Want to find out how to grade your assessments electronically using rubrics? Curious to know how you can streamline your marking by using quantitative and/ or qualitative rubrics?

Come along to this LT lunchtime session to find out more about how to enhance and enrich feedback for your students using these tools in NILE.

Tuesday 13 June – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Tuesday 5 September – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Monday 27 November – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Please sign up here: http://bit.ly/2pNL0H8

Assessments (Groups)

Groups are a powerful tool in NILE that can be used to facilitate and manage group assignments, and enable communication and collaboration for students.

If you are interested in seeing how to easily create groups, set an assignment (e.g. Group Presentation or online Debate), AND potentially reduce administration and marking time, whilst still maintaining quality of feedback, then please sign up ….

Wednesday 12 July – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Tuesday 3 October – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Please sign up here: http://bit.ly/2pNRmXb

Assessments (Turnitin Feedback Studio)

Turnitin has a new interface that will be adopted institution wide later on this year – Feedback Studio. Would you like to get ahead of the crowd and get a sneak preview of the new look and feel; to see the features offered by the new interface; see a demo and find out where to seek help and further support?

Sign up to this new LT lunchtime session to find out more.

Monday 7 August – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Tuesday 12 September – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Tuesday 31 October – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Please sign up here: http://bit.ly/2qnc3dB

In addition the following training sessions are currently scheduled for Xerte – N.B. these are 2.5 hours in duration:

Xerte (online content creation tools)

Xerte is a University supported tool used to create interactive e-learning and online content.

In this training session you will be introduced to the software templates, page types, features and tools available to enable you to produce an interactive e-learning session or online content provision.

You will also learn about the importance of instructional design for your e-learning and online content projects, and benefit from some useful hints and tips, technical advice and items relevant to developing e-content generally.

Park Campus, Library, LLS IT Training Room or Tpod

14 June 2017 – 10:00-12:30 (IT Training Room)

29 June2017 – 13:30-16:00 (Tpod)

13 July 2017 – 10:00-12:30 (Tpod)

15 August 2017 – 14:00-16:30 (Tpod)

6 September 2017 – 10:00-12:30 (IT Training Room)

27 September 2017 – 13:30-16:00 (Tpod)

12 October 2017 – 10:00-12:30 (Tpod)

1 November 2017 – 10:00-12:30 (Tpod)

28 November 2017 – 13:30-16:00 (Tpod)

21 December 2017 – 10:00-12:30 (Tpod)

Please sign up here: http://bit.ly/2fYwKpY

Spaces are limited, so do not delay, book today! Unable to attend on these dates? More will be offered on a rolling basis so watch this space. In the meantime, please visit our NILE Guides and FAQs.

As we fly through this year’s exam period and summer approaches, the LearnTech team has been looking ahead to the next academic year and preparing the 2017-18 NILE templates.

This year we have chosen to differentiate between courses taught at the University and those delivered by our academic partners, to reflect the different needs of all concerned. This has led to the creation of separate templates, making for a more tailored student (and staff) experience.

On the back of this, we are pleased to announce that your 1718 module sites have been created and are now ready to receive your content, so you can self-enrol now.

The template and NILE Standards have been updated for 2017-18 following recommendations approved at the University’s Student Experience Committee and Faculty SECs.

You will note that your module sites’ guidance has been streamlined to allow for any necessary dynamic updates throughout the academic year, incorporating links to existing support, thus avoiding duplication and avoiding potentially conflicting advice.

The template is designed to build on last year’s declutter/ updating of content: you should therefore all find yourselves standing in good stead for this year’s plan to copy over only what is required for the coming years teaching. For those of you unfamiliar with the process there is guidance on hand to assist you with this process as well as Learning Technology team members on standby should you require extra support and assistance. Please email LearnTech Support in the first instance or contact your designated LearnTech.

It’s never too early to start, so why not begin now? Consider getting head of the game; enjoy the summer break safe in the knowledge that some of your preparation for the coming academic year is already completed.

NILE is integrated into the learning and teaching process at The University of Northampton and we need to ensure that it is being used effectively by staff in order to provide a quality student experience.

NILE is integrated into the learning and teaching process at The University of Northampton and we need to ensure that it is being used effectively by staff in order to provide a quality student experience.

Building on the guidance which was initially produced in January 2012, the framework has now been updated to cover the minimum standards which are expected on a NILE site. This was approved at University SEC on 10th May, 2017 and subsequently used as the basis for the new NILE templates which have been developed for the 2017/18 academic year.

Melanie Cole achieves tremendous praise from her students who undertook their study using the Xerte e-learning package.

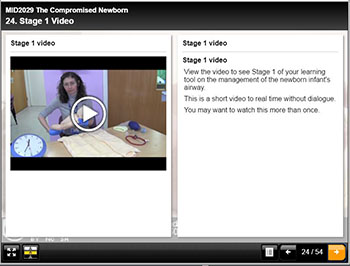

Newborn airway skills teaching and learning

Second year student midwives are required to demonstrate knowledge and manual dexterity skills in key elements of newborn resuscitation while undertaking the undergraduate module ‘The Compromised Newborn’. All those responsible for the care of the newborn infant should be able to provide basic assistance including essential airway management to a baby that does not make a normal transition to extra- uterine life.

The ‘4 stage approach’ is a recognised tool to facilitate acquisition of skills in resuscitation of the newborn infant and is advocated by the UK Resuscitation Council (2015).

Stage 1 – a silent demonstration of the skill by the tutor, allows the learner to observe the skill to real time.

Stage 2 – a demonstration with the addition of tutor dialogue, allows deconstruction of the skill and provides rationale for techniques and the structured approach.

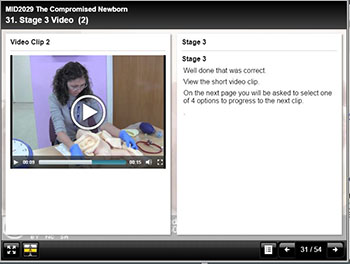

Stage 3 – another tutor led demonstration which encourages the learner to verbally predict the next step and provide commentary for the tutor.

Stage 4 allows the learner to perform the skill independently with tutor and peer support.

Planning an online teaching and learning package

With our future learning environment at Waterside and a shift towards blended learning in mind, I explored the prospect of combining video assisted technology with face to face teaching and learning. My aim was to provide Stage 1, 2 and 3 online and bring the students to the university to consolidate learning and practice new skills during scheduled tutor facilitated contact sessions in small groups. While Kaltura enables the students to engage with stages 1 and 2 in viewing pre-recorded demonstrations of the skill, the challenge was related to Stage 3 and in providing an opportunity for students to be able to engage and contribute online. I contacted Anne Misselbrook from the Learning Technology Team and during a meeting we discussed my requirements and vision for the online resource. Anne quickly identified the Xerte learning package as an e-learning tool that would support my needs and enable Stage 1, 2 and 3 to be delivered online.

Creating an online package

Andy Stenhouse helped me to create the video of the skill being performed in real time (Stage 1) and the video of the skill being performed with tutor dialogue (Stage 2). The video of the skill in real time was then spilt into 10 smaller clips to enable Stage 3 to be created. The students would then be able to view a small clip and choose an answer from a multiple choice question to predict what should happen next. A correct answer takes the student to the next clip while an incorrect answer takes them back to the beginning of Stage 3. The student has to answer each question correctly to get to the end of the sequence and they can have as many attempts as they wish, accommodating individual needs and learning styles.

Six months after I contacted the learntech team the final xerte was embedded into NILE within a series of timetabled learning units and was accessed by the pre-registration midwifery students in October 2016.

These are some quotes from the students who engaged in an online survey following uptake of the xerte learning tool:

Positive Comments

“I found this learning tool extremely helpful and it had the perfect mix of written information and pictures/videos. I feel this will really help me in my practical assessment, if you got a question wrong you had to go back to the beginning which I thought was a really good idea as it enabled you to revisit information that you may not have completely took in and allowed you to keep going over it until this information has stuck”.

“I think the xerte learning tool is of great benefit as it enabled me to go through the learning stages at my own pace and I am able to revisit the information as often as I want in preparation for my assessment. I especially found the videos useful and with these found the content easier to understand”.

“I thought it was extremely useful. The videos were excellent. A good variety of media used too which encouraged learning. I found it very helpful”.

“Overall this tool was brilliant to aid our learning and being able to go back to the videos and quizzes will be very helpful before the assessment”.

“I thought the learning tool was excellent and a great help to my understanding of the topic. So much better than reading a book about it”.

“I believe this to be an excellent method of learning, as you can view the correct way to manage the airway and view it as many times as you wish”.

“A really good learning tool. Easy to follow and in order, making it easy to revise and understand”.

“The videos were really good, easy to understand and clear”.

“I felt the videos very useful especially as I believe I am a visual learner”.

Suggestions for modification

“Instead of going back to the beginning when getting an answer wrong, perhaps just show it is the wrong answer and give another opportunity to select correct answer”.

“Having to go right back to the beginning if you had got a question wrong was slightly frustrating although it did make me remember information so there were definite pros and cons to that process”.

Concluding reflection

Anne provided customised training and valuable support throughout the design and implementation phases. Time for early engagement and collaboration between myself and the Learning Technology Team proved to be vital in the planning, configuring and embedding of Xerte into the module. Inputting theory (text and images) is relatively straightforward on Xerte, creating the activity in Stage 3 and embedding the videos was more complex.

I imagine this approach might be suitable for other practical skills based teaching and learning within the university and I would encourage academic colleagues to give it a try with the support of the Learning Technology Team.

The LearnTech Team is pleased to bring you the next three months programme of LearnTech lunchtimes, following on from the success of our inaugural offerings.Thanks to those of you who have already attended: we hope that you have managed to apply & implement some of what you have learnt for the benefit of your students. For those of you as yet unfamiliar with the concept, read on….

We will once again be introducing you to the various NILE tools, their potential applications and how these technologies can enhance your teaching and learning. Sessions are being offered at both Park and Avenue Campuses and we have a few new additions to whet your appetite, so book now and come along to receive updates, refresh your skills and find out how your peers are working using UN-supported LearnTech tools. Feel free to bring along your own lunch – tea and coffee will be provided.

We look forward to welcoming you over the coming weeks. Details, dates and booking links follow:

Kaltura/ MediaSpace (video)

As the University has now moved to a single video solution in Kaltura (MediaSpace), this is a chance for those who have already started to engage with this tool and those as yet to experience it. The session covers an introduction to MediaSpace; video capture using CaptureSpace; uploading video to MediaSpace; embedding video content in NILE; using quizzes in Kaltura.

Friday 17 March – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, IT Training Room

Friday 30 March – 12:30-13:30 – Avenue Campus, Library, CTC

Tuesday 11 April – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Monday 8 May – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Please sign up here:

(Park Campus): http://bit.ly/2fWkTbG

(Avenue Campus): http://bit.ly/2gAKcQx

Collaborate (Virtual Classroom)

This session will introduce those new to using online virtual classrooms (Northampton is licensed for Collaborate: Ultra Experience) as well as for those who are curious to learn about new functionalities now available in the tool. Topics covered include: setting up the tool in your NILE sites; inviting attendees; sharing files/ applications/ the virtual whiteboard; running a virtual classroom session; moderating sessions; recording sessions; break-out rooms.

Tuesday 21 March – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Thursday 23 March – 12:30-13:30 – Avenue Campus, Library, CTC

Friday 21 April – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Monday 22 May – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, IT Training Room

Please sign up here:

(Park Campus): http://bit.ly/2eG7mZR

(Avenue Campus): http://bit.ly/2hwElOv

MyPad / Edublogs (blogging tool)

MyPad (Edublogs) is the University’s personal and academic (WordPress) blogging tool and can be used in a number of ways to communicate and share learning resources. Topics covered include: creation of individual / class student blogs; use of menus/ media; blog administration within modules; creation of class websites.

Tuesday 4 April – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Friday 28 April – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Friday 30 May – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Please sign up here: http://bit.ly/2f4BEUM

Assessments (Rubrics)

Have you heard about the use of rubrics in NILE and wondering what all the fuss is about? Want to find out how to grade your assessments electronically using rubrics? Curious to know how you can streamline your marking by using quantitative and/ or qualitative rubrics?

Come along to this LT lunchtime session to find out more about how to enhance and enrich feedback for your students using these tools in NILE.

Tuesday 28 March – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Please sign up here: http://bit.ly/2n1m8xu

Assessments (Groups)

Groups are a powerful tool in NILE that can be used to facilitate and manage group assignments, and enable communication and collaboration for students.

If you are interested in seeing how to easily create groups, set an assignment (e.g. Group Presentation or online Debate), AND potentially reduce administration and marking time, whilst still maintaining quality of feedback, then please sign up ….

Thursday 4 May – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Please sign up here: http://bit.ly/2n1sRI1

Assessments (Turnitin Feedback Studio)

Turnitin has a new interface that will be adopted institution wide later on this year – Feedback Studio. Would you like to get ahead of the crowd and get a sneak preview of the new look and feel; to see the features offered by the new interface; see a demo and find out where to seek help and further support?

Sign up to this new LT lunchtime session to find out more.

Monday 15 May – 12:30-13:30 – Park Campus, Library, Tpod

Please sign up here: http://bit.ly/2mjnTml

Spaces are limited, so do not delay, book today!

In addition the following training sessions are currently scheduled for Xerte – N.B. these are 2.5 hours in duration:

Xerte (online content creation tools)

Xerte is a University supported tool used to create interactive e-learning and online content.

In this training session you will be introduced to the software templates, page types, features and tools available to enable you to produce an interactive e-learning session or online content provision.

You will also learn about the importance of instructional design for your e-learning and online content projects, and benefit from some useful hints and tips, technical advice and items relevant to developing e-content generally.

Places are limited to six per session. Contact: anne.misselbrook@northampton.ac.uk for more details.

Park Campus, Library, LLS IT Training Room or Tpod

29 March 2017 – 10:00-12:30 (IT Training Room)

13 April 2017 – 10:00-12:30 (Tpod)

5 May 2017 – 10:00-12:30 (Tpod)

23 May 2017 – 14:00-16:30 (Tpod)

14 June 2017 – 10:00-12:30 (IT Training Room)

29 June 2017 – 13:30-16:00 (Tpod)

13 July 2017 – 10:00-12:30 (Tpod)

15 August 2017 – 14:00-16:30 (Tpod)

6 September 2017 – 10:00-12:30 (IT Training Room)

Please sign up here: http://bit.ly/2fYwKpY

Avenue Campus, Library, CTC

Wednesday 3 May – 14:00-16:30

Wednesday 24 May – 14:00-16:30

Please sign up here: http://bit.ly/2ng6wqq

Unable to attend on these dates? More will be offered on a rolling basis so watch this space. In the meantime, please visit our NILE Guides and FAQs. Still need help? Please contact your assigned LT direct.

We’ve written a few posts about learning styles in the past, and an important letter in yesterday’s Guardian added yet more support to the anti-learning styles side of the argument. Thirty academics signed a letter to the Guardian calling for teachers to end the use of learning styles and to make more use of evidence-based practices instead. Regarding the use of learning styles, the letter said that they were “ineffective, a waste of resources and potentially even damaging as … [they] can lead to a fixed approach that could impair pupils’ potential to apply or adapt themselves to different ways of learning.”1

You can read the entire letter here: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2017/mar/13/teachers-neuromyth-learning-styles-scientists-neuroscience-education

References

1. Sally Weale (2017) Teachers must ditch ‘neuromyth’ of learning styles, say scientists

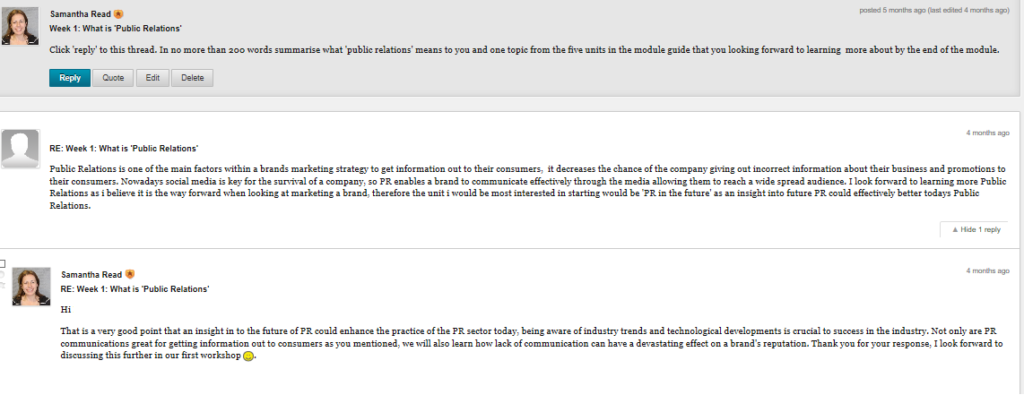

Discussion boards aren’t the latest NILE tool on the block, however FBL lecturer Samantha Read proves it can be an effective tool for extending learning beyond the classroom.

Conversations about discussion boards often reveal how these require ongoing commitment and thoughtful planning. For this post I spoke to marketing lecturer, Samantha Read, and learning designer, Elizabeth Palmer. These are their top tips for successful discussion boards:

- Link your discussion board with classroom activities and teach the tool

As a lecturer who uses discussion boards extensively with large cohorts in FBL, Samantha Read explained the way she combines discussion boards with classroom teaching in these simple points:

- As part of an e-tivity before the workshop session, I encourage students to share their initial ideas and research, with each other and myself, before we discuss them in more detail and apply the theory in the classroom

- During the classroom session as part of group-work students record what their group has covered during the face-to-face time and use this as feed-forward to the next group session

- After the classroom session, students are asked to reflect on what they have learnt during our workshop and receive tutor feedback on their understanding of the classroom content

Of her students’ digital literacy she says, “It is easy to assume that our ‘tech-savvy’ students will be able to use the discussion boards but I have found that many find them difficult. I would therefore suggest that time is taken during a face-to-face session to go over the purpose for using discussion boards as well as demonstrating the basics – what is the difference between a forum and a thread, how to add a post, how to reply to a post, how to embed an image or a video, and how posts can be deleted.”

2. How do I set a task that is sufficiently interesting for discussion?

One of the biggest challenges of discussion boards is motivating students to engage with topics. Learning designer Elizabeth Palmer gives some clear advice on how to maximise online discussions:

“Make sure you set the parameters of the discussion to include guidance on both ‘how’ students should complete the task and ‘why’ it is important. Students that are unable to see the purpose of the task (in both the short and the long term) will be unlikely to engage. Actually this is true of any task in whatever format, class or on-line, not just discussion boards. Equally, if they do not have clear instructions for the task this impacts motivation and likely engagement. Instead of ‘respond to at least two of your peers’ try something like ‘select one answer you disagree with and justify your opposing view with evidence’.

Generally, I advise staff to avoid setting a task that only has one or a limited set of answers because whoever gets there first completes the task. So either encourage personal responses or select an area for discussion that has sufficiently contentious issues for debate to make discussion lively, worthwhile and complex.”

3. Set your students’ expectations for feedback and provide rewards

Imagine a motivated student’s reaction when after spending hours writing a post they find no one has taken the time to read it. Flip this and think about the less motivated student’s feelings if they know their efforts are not being monitored or checked. In both cases students will quickly lose interest in online discussion.

Samantha Read’s structured approach to discussion boards involves placing a deadline date for all posts to be posted, with a given date that the tutor will go into the discussion board and provide feedback.

On modelling best practice she says, “Discussion boards need to be seen as a ‘safe space’ in order for students to feel comfortable posting to them. I always begin each thread with an example post so that the students know the kind of information to include, as well as the suggested length. It is also vital that the discussion boards are monitored and responded to.”

For maximum effect careful planning and maintenance is required. However, if you are aware from the outset that you have limited time to invest outside of the classroom, then you may wish to consider thinking creatively about how the students will interact with the task.

Approaches such as splitting the discussion into groups and allocating group leaders to report back at the beginning of the next lesson will ensure that the students’ efforts are rewarded with feedback.

Gilly Salmon (2017) promotes online socialisation as the bedrock of successful online engagement, identifying the ‘e-moderator’ as ‘a host through which students learn the framework of an e-activities, ‘providing bridges between cultural, social and learning environments’.

Samantha Read reflects on how active participation in discussion boards is an easier path to better grades within her face to face time in the classroom, “I usually make a point at the beginning of the session where discussion board feedback was necessary as part of the learning experience, that those who did participate now have less work to do in the session than those who did not and highlight how these students have shown analytical thinking that will earn them good grades once this is applied to their assignment.

I sometimes even ask the students who did not participate across the course of the week, to make their contribution during class so that we can all benefit from their opinion. This only really works however if a great deal of research was not required for the discussion board task. I also reward students through positive feedback to their posts, making suggestions for how their opinion or research could be used in relation to an upcoming assessment or workshop activity.”

In her final thoughts, Samantha says that “It is worth trying discussion boards as part of your blended learning module to try out virtual ways of increasing engagement. I have found some of my groups have really enjoyed interacting on discussion boards, whilst other groups have found them daunting and needed more support. Each student is going to have a different response but as long as support is available to them, it is definitely worth introducing and seeing that happens.”

What are your experiences?

If you have used discussion boards, what are your thoughts? Be sure to post below and share your experiences and thoughts.

Continue reading »

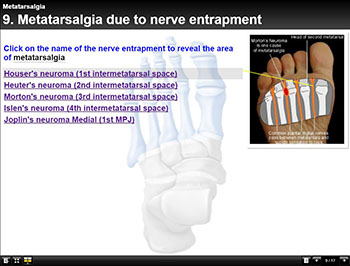

Dr Paul Beeson BSc, MSc, PhD, CSci, FCPM, FFPM RCPS(Glasg), FHEA, a Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Health and Society attended two Xerte training sessions with Anne Misselbrook the Content Developer on 19 April 2016 and again on 11 August 2016.

After attending the August session, Paul started to build his Xerte e-learning packages. Paul took a sensible approach to the Xerte development and contacted Anne for support and they met on 16 August to discuss the plan for Xerte. Paul acknowledges the importance of storyboarding with instructional design. Paul was able to put the content in order in a plan before using Xerte software. Anne helped Paul with designing the structure of the Xerte package with instructional design, provide recommendations about page types to use, and show Paul how he could ‘duplicate’ his Xerte for re-use with different content, thus saving time.

Anne emphasised that the Xertes need to be interactive and future proof.

Andy Stenhouse and Rob Farmer from the Learning Technology team got involved with supporting Paul with video clip recordings.

Paul needed video clips to complement his content and has since embedded quizzes to some of these using Kaltura CaptureSpace.

Paul has developed an impressive 21 Xerte e-learning packages (11 Xerte packages for the 2nd years and 10 Xerte packages for the third years).

At the end of September Paul added the survey questionnaire to his NILE sites.

Sample questions asked include:

- Overall do you think that the Xerte’s are of benefit to learning and why?

- What are your feelings to this approach to teaching?

Paul made the survey a mandatory part of the course and got the 2nd and 3rd year students to complete the survey at the end of term once they had used the different topic Xertes.

Anonymous feedback comments referring to the first question above include:

“Yes, the visual learning of video clips is especially beneficial”.

“I really enjoy the pre learning xerte, it sets me up with some base knowledge and understanding – giving me the foundations to build on within the lecture but also allowing me to bring something to the lecture”.

“It has been very helpful with pre-lecture learning”.

Anonymous feedback comments referring to the second question above include:

“I found it very useful”.

“It’s really good! It has everything we need to know about the topic”.

“Very satisfied, uses a different approach”.

However there does seem to be a misunderstanding about the delivery of teaching. See the feedback comments below:

“It is a good extra to the lecture but nothing can be better than good time spent with the lecturer. The face to face style is needed for this course”.

“I enjoy this style of learning when used in conjunction with the lecture”.

“Teaching is favoured fills the gaps of the Xerte’s”.

The Flipped Classroom is the teaching style being promoted and this is a mix of online and face to face learning. Some students are indicating that they think online is replacing face to face, but this is not the case.

Paul states:

“Lessons learnt include making sure the e-learning package is varied and not too long. Also, the importance of making a plan prior to construction of the Xerte. This can’t be emphasised enough”.

What Paul liked:

It was useful to have the opportunity to attend a Xerte training session more than once as this helps reinforce learning.

Paul liked the direct phone support provided by Anne Misselbrook and the opportunity of being able to share his Xerte examples with Anne for her feedback.

In addition, Paul looked at websites to find examples of good practice.

Conclusion

Students need to have a shift of attitude from the thought that “they (Lecturers) are making us do this” to accepting the message (from Lecturers) “we’ve done this for you and we are helping you by giving a structure and a piece of work useful for your learning and for revision” says Paul.

Paul states that we are giving the e-learning to students to enable their learning and to help facilitate learning in a different way.

Paul feels that using Xerte e-learning packages makes his course cutting edge and interesting for students. E-learning gives another option for how students learn.

Following the successful roll out of our first LearnTech Lunchtime sessions we are delighted to announce that we are now able to offer parallel sessions at Avenue Campus.

The first two will cover Kaltura / MediaSpace (video) and Collaborate (Virtual Classroom Tool). Details as follows, with more sessions to be announced in the New Year (so please watch this space!):

Kaltura/ MediaSpace (video) –

Wednesday 18 January 2017 – 12:30-13:30 – Avenue Campus, Library, IT Training Room 1

As the University has now moved to a single video solution in Kaltura (MediaSpace), this is a chance for those who have already started to engage with this tool and those as yet to experience it. The following areas may cover an introduction to MediaSpace; video capture using CaptureSpace; uploading video to MediaSpace; embedding video content in NILE; using quizzes in Kaltura.

Please sign up here: http://bit.ly/2gAKcQx

Collaborate (Virtual Classroom) –

Thursday 2 February– 12:30-13:30 – Avenue Campus, Library, IT Training Room 1

This session will introduce those new to using online virtual classrooms (Northampton is licensed for Collaborate: Ultra Experience) as well as for those who are curious to learn about new functionalities now available in the tool. Topics may cover some of the following: setting up the tool in your NILE sites; inviting attendees; sharing files/ applications/ the virtual whiteboard; running a virtual classroom session; moderating sessions; recording sessions; break-out rooms.

Please sign up here: http://bit.ly/2hwElOv

Spaces are limited, so do not delay, book today! Unable to attend on these dates? More will be offered on a rolling basis so watch this space. In the meantime, please visit our NILE Guides and FAQs.

Recent Posts

- Blackboard Upgrade – January 2026

- Spotlight on Excellence: Bringing AI Conversations into Management Learning

- Blackboard Upgrade – December 2025

- Preparing for your Physiotherapy Apprenticeship Programme (PREP-PAP) by Fiona Barrett and Anna Smith

- Blackboard Upgrade – November 2025

- Fix Your Content Day 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – October 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – September 2025

- The potential student benefits of staying engaged with learning and teaching material

- LearnTech Symposium 2025

Tags

ABL Practitioner Stories Academic Skills Accessibility Active Blended Learning (ABL) ADE AI Artificial Intelligence Assessment Design Assessment Tools Blackboard Blackboard Learn Blackboard Upgrade Blended Learning Blogs CAIeRO Collaborate Collaboration Distance Learning Feedback FHES Flipped Learning iNorthampton iPad Kaltura Learner Experience MALT Mobile Newsletter NILE NILE Ultra Outside the box Panopto Presentations Quality Reflection SHED Submitting and Grading Electronically (SaGE) Turnitin Ultra Ultra Upgrade Update Updates Video Waterside XerteArchives

Site Admin