Written by Sylvie Lomer and Elizabeth Palmer.

“Why should I even be doing this no one else can be bothered…”

“If I think it is going to benefit me then I will do it, if I don’t I won’t”

“It’s all so boring and hard, I can’t be bothered”

These are the kinds of phrases every teacher dreads overhearing in whispers in class, or in the corridors or even straight to our faces! Instead, we hope against hope for the student that at least trusts us enough to go with the flow….

“For me, I just do it anyway even if it’s not compulsory I’m probably going to do it because there’s a good reason someone has set it up”

…and even more so for that keen student, bright eyed at the front, hand raised, prepared and ready to go!

This blog post deals specifically with what might constitute ‘student engagement’ and the fact that it is often hard to tell what ‘non-engagement’ looks like. In addition, it hopefully goes some way towards establishing that there are different ways to support engagement and that both staff and students need to develop the right skills to foster high levels of engagement under active learning pedagogical models.

What is ‘Engagement’?

Active learning gives preference to group work, co-production, discussion and debate because its pedagogical underpinnings are based on relational and social learning theories. Engagement in these activities is, supposedly, easily observable. Students are either talking, writing, creating etc. or not. One of the difficulties faced by lecturers when moving to such models of learning is the discovery that engagement is not, in fact, as easy to measure as one might assume and that the characteristics of engagement that are easily observed in active learning favour more vocal and confident students. This may leave teachers with a group of students who are not observably participating in these activities. This gives rise to concerns about engagement and participation levels. Are those students that are not vocal, not participating, not creating or ‘doing’ the learning task not engaging and by proxy not learning?

If we begin by assuming that engagement is not necessarily:

-

Verbal

-

Written

-

Product-based

-

Observable

-

What teachers expect.

Then what is it and how do we support it?

Fredericks, Blumenfield and Paris (2004) talk about 3 dimensions to engagement: behavioural, emotional, and cognitive. This suggests that a student could exhibit what we might constitute as observable behaviourally positive engagement through regular attendance and completion of all tasks and assignments, but still be emotionally alienated by the material and therefore, not necessarily have learnt anything (cognitive engagement). In this example has the student ‘engaged’ and does that represent quality learning?

An online environment makes visible things which are present in traditional classrooms, but may remain implicit. In online contexts, for example, we might presume that to be engaged, students must be contributing to discussion boards, raising hands in virtual classrooms, writing blog posts, commenting on classmates’ contributions, and so on. But a small proportion of students are watching the discussions unfold. They may still be learning by watching. Indeed this is part of established learning models, such as Kolb’s learning cycle.

Undoubtedly, there are always some in a given group whose silence reflects confusion, uncertainty, sleepiness, or alienation. But arguably, it is possible to listen actively, to take effective notes and learn by doing so. Sometimes silence is an indicator of thought, of processing, of reflection, of listening.

Not all forms of engagement look the same. So how do you as a teacher determine whether silence is problematic or a different form of engagement?

If it’s online, set the tracker on each of your learning activities. You will be able to see who has accessed each learning activity, even if they have not made a written contribution. Contact them and ask what’s going on, non-confrontationally. Look for changes in patterns. A decline or shift in regularity of tracking patterns might indicate that the student is struggling. This requires regular involvement from the tutor, checking the statistics on the VLE and responding to individual students where appropriate.

If it’s face-to-face, ask questions as you circulate through the groups. Check in with students who seem quiet – have they understood the task? are the group dynamics excluding them? Think about whether they can participate in an alternative mode (e.g. make notes and pass them on). Make this check in personal – ask how they are, whether something is going on, this helps students to feel heard as an individual not just a collective.

Once you’ve determined that there is an engagement problem, the next step is to understand why.

What creates barriers to engagement?

Firstly, and fairly obviously, it’s worth considering prior assumptions about why students are not engaging. They may not be engaging for a number of reasons, some of which are outside their control. There is no meaningful category of ‘disengaged students’ and even students exhibiting “inertia, apathy, disillusionment, or engagement in other pursuits” (Krause, 2005, p.4) may have significant and understandable reasons. Indeed students experience different modes of engagement at different times as a continuum rather than as innate characteristics or traits. Whilst some modes of engagement may be desirable and some may not be, categorising students in relation to modes of engagement is unhelpful.

Students may be temporarily disengaged due to personal stress or concerns. They may be more permanently disengaged due to a fundamental breakdown in one or more of the three dimensions of engagement. If a student is in this situation, telling them to engage is probably not going to work. Asking them whether they are OK or why their engagement patterns have changed may be enough to show them that they are heard and seen as a whole person and they may consequently re-engage. Other times it may be necessary to implement a longer term strategy.

Often, it is necessary to address implicit requirements and skills for effective participation in learning activities. For example, many students in their first year are expected to engage in seminar debate and discussion. For many, this is a first. They may not have the requisite transferable skills of listening, building on contributions, negotiating, synthesising, and courteously disagreeing. These are sophisticated, high order thinking skills which are not innate to any of us. Scaffolding activities and modelling good practice, starting with easier tasks and concrete learning activities is vital.

Assumptions about requisite implicit skills extend to teachers as well. Facilitation of discussion and group work is an extremely challenging task and most of us have never been formally taught either how to formulate questions for discussion or how to stimulate and continue the discussion (or other learning activities). Anyone who has been to a conference will know that discussions do not emerge automatically and can be very difficult to manage. It is worth asking, therefore, whether it is our own uncertainties and fears, subconsciously perceived by students, that underlie disengagement. Beginning to address issues of engagement amongst a student cohort invariably starts with necessary self-reflection and personal development. Finding problems with engagement in our classes and recognising we need help is a particularly hard thing to admit to as it can feel like a loss of face. Often we try to identify a solution or solutions on our own, feeling unable to admit to the problem or indeed not knowing where, or from whom, to get support. Engaging in collaborative peer observation that is not in any way linked to performance management processes can be a start to this. Sometimes having a second pair of eyes and ears in the room can help spot things that it is difficult to do alone.

How do I improve engagement?

Our role as teachers, then, is to establish the conditions in which all students can and do engage in different ways at different times. Learning design, in all its facets, is the key means to tackling this effectively.

As a starting point this may mean reflecting on the content. Get engaged/ re-engaged yourself! Are you excited about this session/ module? Do you think this is a really interesting topic? Are you looking forward to spending time with your students? Are you keen to see what they learn and how they respond to the learning activities you have so carefully created? This must seem incredibly obvious, but often over the course of many years of teaching a subject, it is easy to underestimate the power of a teacher’s authentic emotions on the outcome of a class. The demands on a lecturer’s time and emotional energy have increased exponentially over the last few years and it is easy to become alienated ourselves from our discipline and our desire to educate. Our own well-being as practitioners has a significant impact on our students. A sense of excitement about learning and growth within our field is as important for us as it is for our students. Teachers can be gatekeepers for students into their profession, and modelling continuous learning and development offers opportunities to make learning relevant to future practice. If you can communicate your enthusiasm, students will pick up on your engagement. In an active learning model, having projects in your professional field that you are working on and enjoying can be a useful basis for case studies, work experience opportunities for your students, collaborative student research etc.

Secondly, be transparent, open and honest with respect to your pedagogy. If you’re not sure about something, or if you are trying something new and you don’t know how it’s going to work, tell your students. Ask them for their feedback and cooperation. Ask for their help. Most students will be delighted to be treated as equals in this scenario, and very few will take advantage of it. Student agency in the design and implementation of their learning is highly important and often a successful way of raising engagement in a cohort. Equally, give students some control and agency within the learning activities and tasks. For a given task, give choices about how to complete it. This can be individual or a group discussion about how best to complete the task – this is often a brilliant opportunity for meta-cognition or explicit reflection on learning. In relation to technology-enhanced learning this can also be a means of extending digital literacy within a class. Whilst you may not be aware of the range of technology available for a given task, the collective has a wider reach. Provide opportunities for students to share practice to extend learning and tech usage beyond themselves.

Thirdly, engage in staff development to increase your facilitation skills for both face-to-face and online environments, so that in group work you can effectively manage the dominant members of the group in order that there is space for more reticent students to develop their ideas. It can be helpful to alert students in advance so that they can prepare for the activities (e.g. tell them what the discussion topic will be). This gives students more time to process, collect their thoughts, develop arguments etc. before they are required to discuss the content with classmates. In a blended learning scenario, this can be a significant strength. Online preparation activities can be developed to allow students the time to reflect on issues, in advance of face-to-face sessions. Virtual classrooms allow students to raise their hands, ask questions and participate without being seen by the rest of the class. Therefore, use of virtual classrooms in addition to face to face sessions can offer alternative means of participation. Students that might never raise their hand in class normally, often do in an environment that offers greater anonymity and reduces the risk of embarrassment.

Coming back to the 3 dimensions to engagement – behavioural, emotional and cognitive – we can, and must, examine our learning activities and environments to foster all 3 dimensions.

What does that mean for how we understand ‘engagement’?

All of this suggests a need to re-conceptualise the notion of engagement. The key thing is the recognition that student engagement is the responsibility of both students and their institutions (including the teaching staff) (Witkowski, 2015; Morrison, 2014). Dealing with a ‘lack’ of student engagement should, therefore, not constitute a blame game. Instead it is about genuine, open and honest conversations about how learning should take place and what our mutual roles are between those involved in the learning. At Higher Education level the agency of the students is key but must be understood in the context of the structures within institutions. Here’s one possible, working definition:

Student engagement is concerned with the interaction between the time, effort, and other relevant resources invested by both students and their institutions intended to optimise the student experience and enhance the learning outcomes and development of students and development of students and performance and reputation of the institution (Trowler, 2010).

If any of the content of this blog post has caused you to want help in identifying or problem solving for engagement in your module please contact: LD@northampton.ac.uk

References

Fredricks, J.A., Blumenfeld, P.C. and Paris, A.H. (2004) School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence. Review of Educational Research. 74 (1), pp. 59–109. In: Trowler, V. (2010) Student engagement literature review. Department of Educational Research, Lancaster University. The Higher Education Academy. Available at: http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/staff/trowler/StudentEngagementLiteratureReview.pdf (Accessed on 2nd September 2016)

Krause, K. (2005) Understanding and Promoting Student Engagement in University Learning Communities. Paper presented as keynote address: Engaged, Inert or Otherwise Occupied?: Deconstructing the 21st Century Undergraduate Student at the James Cook University Symposium ‘Sharing Scholarship in Learning and Teaching: Engaging Students’. James Cook University, Townsville/Cairns, Queensland, Australia, 21–22 September. In: Trowler, V. (2010) Student engagement literature review. Department of Educational Research, Lancaster University. The Higher Education Academy. Available at:http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/staff/trowler/StudentEngagementLiteratureReview.pdf (Accessed on 2nd September 2016)

Morrison, Charles D. (2014) “From ‘Sage on the Stage’ to ‘Guide on the Side’: A Good Start,” International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. 8 (1) Article 4. Available at:http://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/ij-sotl/vol8/iss1/4 (Accessed on 2nd September 2016)

Witkowski, Paula, & Cornell, Thomas. (2015). An Investigation into Student Engagement in Higher Education Classrooms. InSight: A Journal of Scholarly Teaching, 10, pp.56-67.

What is “blended learning”?

“Blended learning” is an umbrella term, referring to learning activity that happens across contexts. The ‘blend’ is usually between learning activity happening inside and outside the classroom, or between learning that happens in real-world and online environments (or both!). Many of us learn in this way every day, informally – we might look up information in books and online, discuss it with peers over coffee and via email, draft new ideas on paper and on the laptop. As technology becomes ubiquitous, we need to be able to take advantage of both physical and virtual learning opportunities, to recognise the strengths and weaknesses of each, and to synthesise learning from different contexts. The challenge for educators is to design the right ‘blend’ of activity – both to support specific learning, and to help students to develop their independent learning skills for the future.

“Blended learning” is an umbrella term, referring to learning activity that happens across contexts. The ‘blend’ is usually between learning activity happening inside and outside the classroom, or between learning that happens in real-world and online environments (or both!). Many of us learn in this way every day, informally – we might look up information in books and online, discuss it with peers over coffee and via email, draft new ideas on paper and on the laptop. As technology becomes ubiquitous, we need to be able to take advantage of both physical and virtual learning opportunities, to recognise the strengths and weaknesses of each, and to synthesise learning from different contexts. The challenge for educators is to design the right ‘blend’ of activity – both to support specific learning, and to help students to develop their independent learning skills for the future.

There are two key principles to remember if you’re new to blended learning. The first is to start with the right task for the learning, and then find the right tool (don’t choose a tool and then try to find a use for it!).

The second principle is the ‘blending’ part. The idea of this is that one type of learning activity supports and feeds into the other, and connections and transferability are clear.

Getting started with blended learning

You can ‘blend’ almost any kind of teaching, by starting to add in activities that help students bridge the learning they are doing inside and outside taught sessions. There is no ‘one size fits all’ approach, because each learning activity will depend on what you want to achieve. Starting small, with one type of activity or tool, can help you and your students build confidence and skills, and figure out what works well and what doesn’t. Here are some tips for designing learning activities online:

- Identify learning that can be done outside class time. Sometimes the best way to do this is to think about what you would really like to be able to do with your students in the classroom, and work backwards. Storyboarding can help with this.

- Design the right activity to support the learning. What should the student be doing in order to learn this? Who else should be involved? What resources will they need? Prompts like the Hybrid Learning Model cards can help you to frame different kinds of learning activities.

- Once you have a clear idea of what you want to happen, then choose the right tool to support this type of activity. The University provides a core set of tools that we have vetted for you. Beyond this there are hundreds of possibilities! All of these have strengths and weaknesses, but don’t worry, you don’t need to be a tech guru. The Learning Technology team can help with this.

Many people begin by transferring a learning activity that they already know works well into the online environment. For example, if you would usually ask your students to discuss a contentious idea, or defend a position in a debate, you could do this in an online forum, or if you would usually demonstrate something for the students, you could do this using video. If you’re a little more confident, you might want to think of some ways that technology can extend your teaching and allow you to do things that you couldn’t do in a traditional face to face setting. You might use it to connect students to resources, peers or external experts. You might use it to provide visualisations of text-based materials, or to build knowledge checks that provide students with instant feedback, or to create spaces where they can pool their own resources and ideas to inform their work.

Many people begin by transferring a learning activity that they already know works well into the online environment. For example, if you would usually ask your students to discuss a contentious idea, or defend a position in a debate, you could do this in an online forum, or if you would usually demonstrate something for the students, you could do this using video. If you’re a little more confident, you might want to think of some ways that technology can extend your teaching and allow you to do things that you couldn’t do in a traditional face to face setting. You might use it to connect students to resources, peers or external experts. You might use it to provide visualisations of text-based materials, or to build knowledge checks that provide students with instant feedback, or to create spaces where they can pool their own resources and ideas to inform their work.

Tips for success

Be clear about the why and the how. Sometimes staff who try blended learning for the first time find that students don’t engage as they had hoped with the online activity. Student feedback tells us this is usually because either they don’t understand it, or they don’t see the value. When introducing online tasks, it helps to make it clear why they are being used, and how they will help students to achieve the learning outcomes. It’s also a good idea to explain any unfamiliar tools or processes in advance, just as you would when introducing a new task in the classroom. If you can, get a student perspective on your design before you launch it – and maybe try some online courses yourself, to see what it’s like on the other side!

Be realistic. Be aware that creating online resources and supporting online activity might require slightly different skills to the ones you use in the classroom, so allow yourself time to develop these. Think too about the ratio of effort to impact for your module – creating complex professional-looking resources requires a big investment of time in advance, although this may be worth it if there is one sticky concept that students really struggle with early in their studies. On the other hand, you may be able to get the same effect by using existing resources on that topic and asking students to critique them, or even by asking students to research the topic and share their own key resources. You don’t need to be a computer genius (or spend months learning complex software) to create that lightbulb moment!

Learn from others. Working in a team can really help here – not just in terms of sharing the workload and learning new skills, but also in setting consistent expectations for students across different modules on the same programme. If you’re stuck for ideas, have a look of some of our case studies, or ask around to see what colleagues are trying.

Do one thing

Ready to give it a try? If you want help figuring out what to blend, at a session, module or even programme level, the Learning Design team can help. If you already have an idea for an online activity, but you’re not sure about the technology, the Learning Technology team can help. Get in touch and we’ll help you get started!

What are the factors that encourage and inhibit student engagement in online activities, such as e-tivities? This was the question that URBAN project run by Elizabeth Palmer, Sylvie Lomer, Laura Wood and Iveline Bashliyska sought to answer. This blog post outlines some of their findings.

Much research has been done into what makes a ‘good’ e-tivity (Swan, 2001; Sims et al., 2002; Lim et al., 2007; Salmon, 2013; Clark & Mayer, 2011; University of Leicester, n.d.):

- clear instructions and design,

- purposeful,

- perceived relevance,

- practice opportunities,

- interactive,

- structured pathways and sequencing,

- effective feedback

- interactions with the tutor

An amalgamation of tips gleaned from this research, such as Gilly Salmon’s “E-tivities: The Key to Active Online Learning” (available from the University library), and the experience of various University of Northampton staff who have been trialling e-tivities over the past year or so is available here: Tips for etivities and blended learning (PDF) It is not by any means definitive but might be helpful!

The Learning Development team (formally known as the Centre for Achievement and Performance: CfAP) offer a range of transferable cognitive and academic skills development opportunities for students, through both face-to-face and online delivery. Workshops delivered are embedded in subject courses and modules, on request from lecturers and module leaders. In the last year Learning Development has been modifying its delivery of workshops from a solely face-to-face model to a blended model of delivery in accordance with the University’s new pedagogical model. (See the Learning & Teaching Plan and information about Waterside for more detail). The aim of this approach was to provide online activities that would offer scalable opportunities for personalised, independent online learning that provide low pressure opportunities for students to practice academic skills and to maximize the impact of face to face time with students.

A variety of different approaches have been taken to this new blended delivery including; opportunities for structured writing practice; opportunities to shape the content of face-to- face workshops; discussion boards based around students’ concerns with academic and cognitive skills; preparatory writing exercises; interactive activities developing and modelling specific skills such as synthesis and formative individual feedback on written tasks. However, even when following good e-tivity design principles, student engagement with Learning Development designed e-tivities has varied markedly. For this reason a research project in LLS was undertaken to uncover more detail from students about their engagement with e-tivities. The project adopted qualitative methodologies involving students as co-researchers in order to uncover the causes and factors underpinning this variation, focus groups were conducted with staff and students involved in some of the blended learning activities at UoN.

The first finding was that students did not differentiate between CfAP activities and those of their module tutor. As a consequence it is possible to generalise the results as applicable to blended learning activities regardless of the tutor responsible for setting the activities.

The results can be seen to belong to one of two categories: ‘conditions’ for blended learning and ‘factors’ for student engagement. ‘Conditions’ are necessary and universal for all students; if the conditions cannot be met, successful engagement with blended learning through online activities is highly unlikely. Responsibility for conditions lies with staff and institutional policies and engagement. In contrast, the factors affecting student engagement are individual, personal and particular to the student, cohort and discipline. They do not lie entirely within the control of staff; that said they can be supported and bettered through effective educational practices. For example, a student may have low resilience for challenging activities and although staff can support the student in developing better resilience they cannot create resilience for the student; this constitutes a factor. Conversely, staff can establish accessible e-tivities and effectively communicate their purpose and how to complete them; this constitutes a condition.

The conditions and factors are as follows:

Fundamental conditions for Blended Learning:

- Staff engagement and student-staff relationship: This condition highlights the significance of staff motivations, beliefs and approaches to blended learning and relationships with student. Students nearly always mirror the staff’s views.

- Communication: This condition pertains to the requirement that communication between staff and students, around the purpose, pedagogical rationale and instructions for tasks, be fully transparent.

- Well designed VLE and online learning: This condition pertains to issues of design, navigation, layout etc.

Factors impacting engagement with blended learning:

- Student digital literacy and technology preferences: This factor indicates the extent to which individual student engagement with technology impacts variance in student engagement.

- Student beliefs and motivations about and for learning: This factor indicates the way that inherited beliefs about learning in general, and specifically in relation to each individual students patterns of learning, impacts their engagement with blended learning

- Student capacity for self-management: This factor pertains to variance in individuals ability to self-manage their learning and the impact this has on engagement with blended learning.

Initial findings were disseminated at this year’s LLS conference at the University of Northampton and the research team are now in the process of writing these results up for publication in the coming months. For the LLS conference presentation please visit:

For further information on these, please contact Elizabeth Palmer and Sylvie Lomer.

See also Julie Usher’s post on Getting Started with Blended Learning:

So argues Dr Chris Willmott, Senior Lecturer in Biochemistry at the University of Leicester.

In a recent article for Viewfinder, entitled Science on Screen, Dr Willmott discusses his use of clips from films and television programmes in his university bioscience teaching. Dr Willmott considers a number of ways in which clips from science programmes and popular films (even those which get the science woefully wrong) can be used as teaching aids, all of which are designed to promote engagement with the subject, and which can be incorporated into a flipped learning session.

He categorises his use of clips from films and television programmes in the following way, which you can read more about in his article:

- Clips for illustrating factual points

- Clips for scene setting

- Clips for discussion starting

Obviously not all science programmes get things right, but rather than being off-putting, this can be a great starter for a teaching and learning session. In the following example, Dr Willmott explains how he makes use of a clip in which Richard Hammond ‘proves’ that humans can smell fear:

Students are asked to watch the clip and keep an eye out for aspects of the experiment that are good, and those features that are less good. These observations are then collated, before the students are set the task of working with their neighbours to design a better study posing the same question.

If you’re interested in using visual content to aid the teaching of science then there are an increasing number of visual resources available. Dr Willmott mentions the Journal of Visualised Experiments in his article, a journal which is now in it’s tenth year, and which has over 4,000 peer-reviewed video entries. It’s a subscription only journal, and we don’t have a subscription, but if it looks good and you speak nicely to your faculty librarian then who knows what might be possible!

A resource that we do subscribe to is Box of Broadcasts, a repository of over a million films and television programmes. Accessible to academics and students (as long as they are in the UK), BoB programmes are easily searched, clipped, organised in playlists, and linked to from NILE. Plenty of material from all your science favourites such as Brian Cox, Iain Stewart and Jim Al-Khalili and even the odd episode from classic science documentaries like Cosmos and The Ascent of Man.

A free, and very high quality visual resource is the well known Periodic Table of Videos, created by Brady Haran and the chemistry staff at the University of Nottingham. Also of interest to chemists (but not free) are The Elements, The Elements in Action, and the Molecules apps developed by Theodore Grey and Touch Press. Known collectively as the Theodore Grey Collection, these iOS only apps may end up being the best apps on your iPad.

Not visual at all, but still very good, is the In Our Time Science Archive – hundreds of free to download audio podcasts from Melvyn Bragg and a wide range of guests on many, many different scientific subjects from Ada Lovelace to Absolute Zero.

Recent article from TeachOnline.CA entitled “A New Pedagogy is Emerging… and Online Learning is a Key Contributing Factor” does a really fantastic job of outlining current trends in pedagogy and the role that online learning is playing within this new pedagogy. If you haven’t seen it, I recommend having a look!

In summary, the article outlines 7 key elements of current pedagogical thinking as follows:

“1. Blended learning

2. Collaborative approaches to the construction of knowledge/ building communities of practice.

3. Use of multimedia and open educational resources

4. Increased learner control, choice and independence

5. Anywhere, anytime, any size learning

6. New forms of assessment

7. Self-directed, non-formal online learning. “

All these aspects can be seen to underpin the Teaching & Learning plan we are moving towards at the University of Northampton. Blended or Hybrid learning is seen as the new normal where online and technology enhanced learning blend seamlessly with face-to-face workshop time. Significant emphasis is placed on group based learning and social interaction as well as the learner being at the centre of designing, implementing and reflecting on learning experiences.

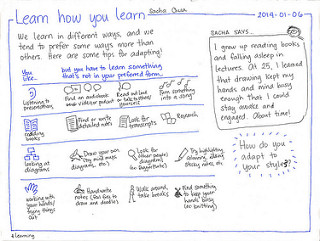

We recently posted a fairly lengthy blog entry about the myth of learning styles in education. The blog post was entitled ‘Question: What’s Your Preferred Learning Style?’ and it looked in some detail at the evidence against the widespread belief that students learn better when presented with information that is in their preferred learning style.

The TEDx video below is highly recommended for anyone with an interest in learning styles. In the video, Tesia Marshik, Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of Wisconsin La Crosse, outlines some of the major arguments against learning styles and explains why, even though such beliefs are mistaken, they are so widely held.

And a belief in preferred learning styles is not the only mistaken belief about learning that is widely held by educators … for more on this see our earlier post ‘Neuromyths in Education’.

Click on the image below to watch the video …

by Robert Farmer and Paul Rice

It’s no easy thing to create an interesting, engaging and effective educational video. However, when developing educational presentations and videos there are some straightforward principles that you can apply which are likely to make them more effective.

The following videos were created for our course, Creating Effective Educational Videos, and will take you through the dos and dont’s of educational video-making.

1. How not to do it!

This short video offers a humorous take on how not to make great educational videos.

- Prof. Oliver Deer discusses his approach to making educational videos: https://youtu.be/cKXx9GkeGGQ

2. Understanding Mayer’s multimedia principles

This 20 minute video outlines Richard Mayer‘s principles of multimedia learning and provides practical examples of how these principles might be applied in practice to create more effective educational videos.

- A Practical Guide to Mayer’s Multimedia Principles: https://youtu.be/m0GMZgaC7gM

3. Applying Mayer’s mutimedia principles

Because much of Mayer’s work centres around STEM subjects (which typically make a lot of use of diagrams, charts, tables, equations, etc.) We spent some time thinking about how to apply his principles in subjects which are more text based. To this end, we recorded a 12 minute video lecture which is very on-screen text heavy in which we tried to make use of as many of Mayer’s principles as possible.

- Are we ever justified in silencing those with whom we disagree? https://youtu.be/Dyu94dH2aeo

4. Understanding what students want, and don’t want, from an educational video

Given the current popularity of educational videos, and given the time, effort and expense academics and institutions are investing to provide educational videos to students, we thought that it was worthwhile to evaluate whether students actually want and use these resources. You can find the results of our investigation in our paper:

- Rice, P. and Farmer, R. (2016) Educational videos – tell me what you want, what you really, really want. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, Issue 10, November 2016. Available from: https://journal.aldinhe.ac.uk/index.php/jldhe/article/view/297

5. Further reading

Mayer, R. (2009) Multimedia Learning, 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press.

https://www.cambridge.org/gb/academic/subjects/psychology/educational-psychology/multimedia-learning-2nd-edition

Rice, P., Beeson, P. and Blackmore-Wright, J. (2019) Evaluating the Impact of a Quiz Question within an Educational Video. TechTrends, Volume 63, pp.522–532.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-019-00374-6

The Learning Design team recently met up with Terry Neville (Chief Operating Officer) and Jane Bunce (Director of Student and Academic Services) to discuss a number of Waterside related issues. Among the subjects discussed were the teaching of large cohorts, timetabling, the working day and the academic year. We video recorded our discussion, and it is now available to view in the ‘Waterside Ready’ section of the staff intranet.

The Learning Design team recently met up with Terry Neville (Chief Operating Officer) and Jane Bunce (Director of Student and Academic Services) to discuss a number of Waterside related issues. Among the subjects discussed were the teaching of large cohorts, timetabling, the working day and the academic year. We video recorded our discussion, and it is now available to view in the ‘Waterside Ready’ section of the staff intranet.

Also available in the same location are three videos from Ale Armellini (Director of the Institute of Learning and Teaching) on the subject of getting ready for Waterside, and one video each from Simon Sneddon and Kyffin Jones, both senior academics, who discuss how they have been preparing for the move to Waterside.

Answer: It doesn’t matter!

Want to know why? Then read on …

The One-Minute Overview

Students don’t really learn better when receiving information in their preferred learning style. Not only is it misleading to encourage them to believe that they do, but it may impair their ability to learn if they think that they have a learning style in which they learn best. However, this does not mean that educators should not use a variety of approaches in their teaching and learning, because students learn best when encouraged to learn in a variety of different ways.

In short, if you’ve been using a variety of approaches to teaching and learning because you wanted to be inclusive and to do something for the visual learners, something for the auditory learners and something for the kinaesthetic learners then that’s great – there’s no problem with that. What the research is suggesting is that you shouldn’t try to get students to figure out what their preferred learning style is and then to suggest that they limit their learning to that style, because that’s not helpful and may be damaging. What is good pedagogy is to vary your approach to teaching and learning because everyone learns better when they learn in lots of different ways.

If you’d like a short and tweetable anti-learning styles quote to back this up, then let me suggest this one from Philip Newton’s 2015 paper ‘The Learning Styles Myth is Thriving in Higher Education’.

The existence of ‘Learning Styles’ is a ‘neuromyth’, and their use in all forms of education has been thoroughly and repeatedly discredited

The Long Article

Introduction

Let me introduce my nightmare learner to you. A scruffy-looking mature student, bearded and bespectacled, he’s been preparing to start his degree by learning about how he learns best, and he introduces himself to you as follows:

“Hi, my name is Rob, and I’ll be studying with you for the next three years. I’ve spent a lot of time analysing the way I learn, so what I’ll need from you, my lecturer, is as follows. I’m an auditory learner, so I’ll need all my material from you in podcast form. I’m also left-brain dominant, so please don’t begin from the big picture and work down to the detail, as that will confuse me and I’ll never learn – I need it the other way around please. And please remember that left-brain learners need logic, rules, facts, sequence and structure in order to learn. Also, I’m an ISTJ according to Myers-Briggs, a Concrete-Sequential learner according to the Mind Styles Model, and a Theorist according to Honey and Mumford, so please bear that in mind when preparing my personalised learning materials. Lastly, and I don’t know how relevant this is, but my star sign is Taurus, so I am loyal and reliable, but can be stubborn and inflexible too. You know, I’m really looking forward to the next three years, and I know that if I’m presented with learning materials that are perfectly suited to my learning style I’ll be able to learn anything.”

This chap is clearly preposterous, and is profoundly confused about the nature of learning. I can say that because he’s me – or, at least a version of me, but one who has been taught that if learning is difficult and is taking too much effort then it’s probably because of a mismatch between the learning materials and one’s own learning style, not because it actually does take some degree of effort to learn new things.

Nevertheless, some things do genuinely impede learning. If someone is worried or anxious about something, if they are very hungry or very tired, if they’re in physical discomfort, if the content is too advanced, if they can’t hear what’s being said or see what’s being shown, or if they’re demotivated for whatever reason then they are not going to be able to learn well, if at all. But do we really want to say that someone will struggle to learn if they’re a kinaesthetic learner and have been given a podcast to listen to? Do we really want to handicap our students by telling them that learning is so specific and individual that they can only learn effectively in one way? Why not free our students by telling them that they all have these amazing brains which can and do learn in many, many different ways? Not only that, but that by embracing a wide range of different approaches to learning they will actually learn better.

Let’s look at the issue from another angle. Why don’t students learning to be doctors learn about phrenology or about the four humors? Why don’t biology students learn about the theory of maternal impression? Why don’t chemistry students learn about phlogiston or about the transmutation of base metals into gold? Why don’t physics students learn about caloric or the emitter theory of light? The simple answer to this question is because none of these ideas has any basis in fact. While they might be taught on course covering the history of science, they would no more be taught as scientific fact than would the geocentric model of the solar system. These are all theories which have been consigned to the scientific dustbin, and rightly so.

As far as education is concerned, we are not without our theories and ideas which we have consigned to the educational dustbin. Brain Gym is already in the dustbin, and has been for some time1, but another idea that should have been consigned to the dustbin of educational ideas is the notion of preferred learning styles. However, over 90% of UK teachers still believe the following statement to be true: ‘Individuals learn better when they receive information in their preferred learning style (for example, visual, auditory or kinaesthetic).’2

Should we be using learning styles?

Broadly speaking, the idea behind learning styles is that students have a ‘preferred learning style’ and that students learn best if they are allowed to learn in their the preferred learning style. Some of the more popular learning style theories include VAK, which classifies students as visual, auditory or kinesthetic learners, and Honey and Mumford, which classifies learners as activists, theorists, pragmatists and reflectors.

In his 2004 book, ‘Teaching Today’, Geoff Petty makes the following very reasonable claim:

“There is strong research evidence that ‘multiple representations’ help learners, whatever the subject they are learning. There is much less evidence for the commonly held view that students learn better if they are taught mainly or exclusively in their preferred learning style.”3

A couple of years later, in 2006, in his book ‘Evidence Based Teaching’, Petty went further, and stated that:

“It is tempting to believe that people have different styles of learning and thinking, and many learning style and cognitive style theories have been proposed to try and capture these. Professor Frank Coffield and others conducted a very extensive and rigorous review of over 70 such theories … [and] they found remarkably little evidence for, and a great deal of evidence against, all but a handful of the theories they tested. Popular systems that fell down … were Honey and Mumford, Dunn and Dunn, and VAK.”4 5

Professor Coffield and his colleagues at Newcastle University produced two reports for the Learning & Skills Research Centre in 2004. One was entitled ‘Learning styles and pedagogy in post-16 learning: A systematic and critical review’ and was a hefty 182 page report in which the literature on learning styles was reviewed and 13 of the most influential learning styles models were examined. The second report was entitled ‘Should we be using learning styles? What research has to say to practice’ and was a shorter 84 page report which focused on the implications of learning styles for educators.

Peter Kingston, writing in the Guardian, summarised the findings as follows:

“The report, Should we be using learning styles?, by a team at Newcastle University, concludes that only a couple of the most popular test-your-learning-style kits on the market stand up to rigorous scrutiny. Many of them could be potentially damaging if they led to students being labelled as one sort of learner or other, says Frank Coffield, professor of education at Newcastle University, who headed the research on behalf of the Learning and Skills Development Agency.” 6

The 2004 reports by Coffield et al., appear to have generated a great deal of interest into the now widely discredited (but still widespread and financially lucrative) area of learning styles, and the evidence against learning styles has been steadily building ever since. For example, a 2008 paper by Pashler et al., published in the journal Psychological Science in the Public Interest concluded that:

“The contrast between the enormous popularity of the learning-styles approach within education and the lack of credible evidence for its utility is, in our opinion, striking and disturbing. If classification of students’ learning styles has practical utility, it remains to be demonstrated”7

More recently, Sophie Guterl, writing in 2013 for Scientific American noted that:

“Some studies claimed to have demonstrated the effectiveness of teaching to learning styles, although they had small sample sizes, selectively reported data or were methodologically flawed. Those that were methodologically sound found no relationship between learning styles and performance on assessments.”8

And to bring things even more up-to-date, Philip Newton’s 2015 paper for the journal Frontiers in Psychology paper stated very clearly that:

“The existence of ‘Learning Styles’ is a common ‘neuromyth’, and their use in all forms of education has been thoroughly and repeatedly discredited in the research literature. … Learning Styles do not work, yet the current research literature is full of papers which advocate their use. This undermines education as a research field and likely has a negative impact on students.”9

Conclusion

Learning styles, it appears, are very much in the educational dustbin … it’s just a matter of time before it becomes widely known that that’s where they are. However, even though 93% of UK teachers believe in learning styles, that was still the lowest percentage of all the countries looked at in Howard-Jones’s 2014 paper ‘Neuromyths and Education’. So perhaps the message is slowly getting across in the UK after all.

The seminal reports about learning styles by Coffield et al., are, like all good pieces of academic work, subtle, nuanced, complex, detailed and resistant to clumsy, reductionist, bite-sized soundbites and simplistic conclusions. The reports themselves are no longer available from the LSRC’s website, but can be easily found in PDF format online (just enter the report title into any search engine). For those wanting more of an introduction and overview then Peter Kingston’s summary of the work, published is the Guardian under the title ‘Fashion Victims’, is an excellent place to start. And if you have a copy to hand, pages 30 to 40 of Geoff Petty’s ‘Evidence-Based Teaching’ are well worth a read. If you want to go directly to the originals, the shorter report ‘Should we be using learning styles?’ is the best one to start with, and the set of tables on pages 22 to 35 of the report summarise the pros and cons of the various systems reviewed, giving an overall assessment of each.

For educators, the most useful guidance on learning styles is probably that provided by Petty on page 30 of ‘Evidence-Based Teaching’, where he summarises the advice from Coffield et al., as follows:

1. Don’t type students and then match learning strategies to their styles; instead, use methods from all styles for everyone. This is called ‘whole brain’ learning.

2. Encourage learners to use unfamiliar styles, even if they don’t like them at first, and teach them how to use these.

Notes and References

1. Fortunately, Brain Gym never really made it into universities, but it was popular in schools for some time. Ben Goldacre did much to expose it as pseudoscience, and wrote about it in detail in the second chapter of his book, ‘Bad Science’, and in various Guardian articles dating back to his June 2003 article, ‘Work our your mind’. Goldacre’s 2008 article ‘Nonsense dressed up as neuroscience’ is a good primer on Brain Gym. James Randerson’s 2008 article ‘Experts dismiss educational claims of Brain Gym programme’ summarises the views on Brain Gym of several prominent scientific associations.

2. For more on this, see Paul Howard-Jones’s 2014 paper ‘Neuroscience and education: myths and messages’ or see Pete Etchells’s summary of Howard-Jones’s research: ‘Brain balony has no place in the classroom’.

3. Petty, G. (2004) Teaching Today, 3rd Edition. Cheltenham: Nelson Thornes, pp.149-150.

4. Petty, G. (2006) Evidence Based Teaching. Cheltenham: Nelson Thornes, p.30.

5. Coffield et al., (2004) provide a set of tables listing the pros and cons and a summary of each of the learning styles on pages 22 to 35 of their report, ‘Should we be using learning styles?’ The overall assessment on each of them makes for interesting reading. The best of systems is Allinson and Hayes’ Cognitive Styles Index (CSI), although Hermann’s Brain Dominance Instrument (HBDI) is also well reviewed.

6. Kingston, P. (2004) Fashion victims: Could tests to diagnose ‘learning styles’ do more harm than good. The Guardian, 4th May.

7. Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D. and Bjork, R. (2008) Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 9(3), pp.105-119.

8. Guterl, S. (2013) Is Teaching to a Student’s “Learning Style” a Bogus Idea? Scientific American, 20th September.

9. Newton (2015) The Learning Styles Myth is Thriving in Higher Education. Frontiers in Psychology, Volume 6 (December 2015).

Further Viewing

Question: What two things do these three statements have in common?

A. Individuals learn better when they receive information in their preferred learning style (for example, visual, auditory or kinaesthetic).

B. Short bouts of co‐ordination exercises can improve integration of left and right hemispheric brain function.

C. Differences in hemispheric dominance (left brain or right brain) can help to explain individual differences amongst learners.

Answer:

1. They are all false.

2. They are all believed to be true by around 90% of UK teachers.

Interested? You can read more in Paul Howard-Jones’s 2014 paper ‘Neuroscience and education: myths and messages‘ or in Pete Etchells’s summary of Howard-Jones’s research, ‘Brain balony has no place in the classroom’.

Recent Posts

- Blackboard Upgrade – February 2026

- Blackboard Upgrade – January 2026

- Spotlight on Excellence: Bringing AI Conversations into Management Learning

- Blackboard Upgrade – December 2025

- Preparing for your Physiotherapy Apprenticeship Programme (PREP-PAP) by Fiona Barrett and Anna Smith

- Blackboard Upgrade – November 2025

- Fix Your Content Day 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – October 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – September 2025

- The potential student benefits of staying engaged with learning and teaching material

Tags

ABL Practitioner Stories Academic Skills Accessibility Active Blended Learning (ABL) ADE AI Artificial Intelligence Assessment Design Assessment Tools Blackboard Blackboard Learn Blackboard Upgrade Blended Learning Blogs CAIeRO Collaborate Collaboration Distance Learning Feedback FHES Flipped Learning iNorthampton iPad Kaltura Learner Experience MALT Mobile Newsletter NILE NILE Ultra Outside the box Panopto Presentations Quality Reflection SHED Submitting and Grading Electronically (SaGE) Turnitin Ultra Ultra Upgrade Update Updates Video Waterside XerteArchives

Site Admin