Introduction and Rationale

Scott Parker ran a Social Work module using a flipped classroom model and social media in order to stimulate analysis, critical thinking and discussion in seeking deeper learning of themes, topics and issues. One of the key issues underlining this project is that online resources and social media should support the more ‘formal’ teaching process rather than replace it totally.

NILE does have the facility to set up ‘blogs’ or discussion boards’ which can offer similar access to learning materials and opportunities for discussion. However the decision to use Facebook as a platform was an effort to shift the focus from purely academic ‘work’ to a more fluid discussion base beyond the confines of lectures and University based software. Scott points out that clearly there are some caveats within this area of study. There is blurring between the personal and private within user’s lives with potentially risky outcomes, for example; comments can be taken out of context and there is the potential for exploitation of vulnerable users.

Relevance to Practice and lecturing role

The volume of information students need to be exposed to far exceeds the modular structures and ‘contact hours’ stipulated by the Social Work programme, one answer to this is utilising online resources such as Panopto recordings (online video/information dissemination recorded by tutors allowing students to watch at their leisure) to utilise the ‘flipped classroom’ i.e. the online materials are used to ‘set the scene’ and present facts/figures/data etc. With the next face to face teaching session used to assess learning via electronic ‘polls’ or seminar work. This can offer insight into individual student learning/understanding and can serve to direct the focus of onward teaching aimed at deeper understanding and potentially further use of social media to engender peer discussion and debate.

Face to face teaching remains an expectation within a University environment; however this must be enhanced by additional activities and resources to enrich the learning process. Use of social media in teaching may also enhance the collaborative nature of learning; students can discuss/debate issues online and potentially this can include the lecturer, particularly when planning an activity or setting a task for students to complete as part of independent study or group work. This can also support effective reflective practice, illustrating how the ‘original’ theme/discussion item has developed and ideas have ‘evolved’ offering effective feedback for reflection.

Size and structure of Group

The cohort focus was upon level 5 Social Work Students engaging on an Adult Services 20 credit module. Out of a total 35 student in the group it was hoped that at least 20 would consider taking part; in the event 24 participated. Scott was also able to seek feedback from students who declined to participate, particularly with respect to their perceived value of digital/social media to learning.

Emerging Themes

The discussion pages material prompted debate; however students clearly expected more ‘stimulation’ of material by the tutor, despite being informed that the discussion page sought to encourage peer debate and discussion students remarked on how the material and discussion challenged their views and thoughts. This illustrates the overall pedagogic value of enhanced opportunities to offer material in varied and accessible ways in supporting student learning and engagement. Additionally when considering student satisfaction, the module evaluation reported a concurrent level of satisfaction in student expectation, engagement and learning outcomes.

Reflection

There was evidence that uses of a range of ‘external’ resources i.e. those outside the formal teaching or seminar structure, add value to student understanding and learning.

The students who did not participate stated that time was a factor in not accessing the discussion page and clearly this was also true of my role as tutor in ‘stimulating’ discussion, as the project took place during a particularly heavy teaching period; this would have to be addressed in using such methods in the future; possible setting aside a specific time to have ‘live’ discussion, which students could engage directly with and after the ‘live’ session contribute or merely read the discussion dialogue. This could then be used as a ‘starting point’ in seminar sessions to make effective links between module teaching material and wider discussion/engagement.

The project also sought feedback regarding the use of Panopto (video/powerpoint) material to support learning. Generally there was a very positive response to the value of this, which again aims to take the teaching out of the formal lecture theatre/seminar session to an accessible and re-useable format. This suggests a mix of learning tools continues to be appropriate in meeting a diverse range of learning styles and whilst this is time-consuming to prepare, the value to learning and the potential enhanced quality in understanding and engagement with material appears worthwhile.

Anecdotally, it appears that there may have been some impact upon academic achievement as the previous year cohort average module grade was C, whilst this year it was B-. Clearly there may be other factors involved in the improvement of student achievement; however the themes identified in this project suggest that additional resources offer tangible benefits to students.

Click Scott Parker Research Project PGCTHE June1014 – v1 to download Scott Parker’s full report “The use and added value of digital resources and social media in supporting formal learning and teaching at HE level”

Dr Terry Tudor, Senior Lecturer in Waste Management, introduced structured online learning activities (e-tivities) into his Masters modules after attending a CAIeRO for individuals course development workshop. Read the case study to see how these activities have helped to link his distance learning students with his learners on campus – and also helped them to improve their writing skills.

One of the more discussed topics at the University of Northampton at present is the idea of the ‘flipped classroom’ or of students engaging in ‘flipped learning’. A major reason why this is being discussed now is that use of the flipped classroom could well be a major feature of the University’s new Waterside campus1, however this is not the only (nor even the best) reason for interest in this subject. As will undoubtedly be clear, the best reason for adopting a flipped learning approach to teaching and learning is that it offers pedagogical advantages, and we will certainly look at some of the evidence in favour of flipped learning in a later blog post. However, our purpose in this post is simply to outline what flipped learning is, and how one might go about doing it.

The key points in this post are:

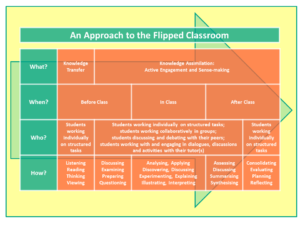

1. Very simply put, the flipped classroom is one where students access content and engage in activities designed to develop their understanding before class, and then use the class time to discuss and engage in depth with issues, ideas and questions arising from the pre-class content and activities.

2. Whilst there may be some barriers to adopting this approach, most (if not all) can be overcome.

3. The flipped classroom is very relevant to the University of Northampton at the moment as it is one of the models of teaching and learning which will work very well in the new Waterside campus. However, there’s no need to wait until we get to Waterside to try it out, as it’s something that will work well right now.

4. There is a lot of support available to staff wanting to try out the flipped classroom, and staff are encouraged to try out this approach to teaching and learning.

What the flipped classroom is

I was introduced to the idea of flipped learning in 2012 by the Harvard Professor Eric Mazur, when I attended his keynote speech2 at the annual conference of the Association for Learning Technology. The idea of the flipped classroom owes a great deal to the work of Mazur, whose ideas about peer instruction3 formulated at Harvard in the 1990s evolved into what we now term flipped learning. To use Mazur’s terminology, what happens in a traditional classroom is that class time is typically taken up with ‘knowledge transfer’, often a lecture, and students then complete tasks outside of class in order to process and understand the subject matter, which Mazur terms ‘knowledge assimilation’. What Mazur proposed is that the knowledge transfer stage should be covered prior to attending class, and that the class time could then be used to help students assimilate what they had read or watched prior to coming to class. The ‘flip’ is simply that knowledge transfer now happens outside class, and knowledge assimilation now happens in class.

“Mazur’s reinvention of the course drops the lecture model and deeply engages students in the learning/teaching endeavor. It starts from his view of education as a two-step process: information transfer, and then making sense of and assimilating that information. ‘In the standard approach, the emphasis in class is on the first, and the second is left to the student on his or her own, outside of the classroom,’ he says. ‘If you think about this rationally, you have to flip that, and put the first one outside the classroom, and the second inside. So I began to ask my students to read my lecture notes before class, and then tell me what questions they have [ordinarily, using the course’s website], and when we meet, we discuss those questions.'” 4

Putting the flipped classroom into practice

Obviously no classes at Northampton are taught only via lectures, and I suspect that very few (if any) lectures at Northampton are pure didactic monologues, but Mazur’s ideas could still be used to good effect to free up more class time to spend with students helping them to understand the material and the subject in more depth.

If this approach appeals to you, then an example of how you could put it into practice is by putting your lectures online, and using your class time to engage students in activities and tasks which will help them to fully understand the material which was covered in your lecture. The online lectures should be short, certainly no more than thirty minutes, but two fifteen minute lectures would be preferable. And supporting the video lectures will probably be some reading, a book chapter or journal article perhaps. Students may watch your lectures a few times in order to get the most from them, and students for whom English is not a first language may benefit greatly from the ability to watch and re-watch the lectures. You’ve now freed up an extra hour to spend with your students, so what’s the best way to use that hour?

Well, there are plenty of options here. If you’d prefer a more teacher-led session then one idea would be to ask your students to complete a pre-class test or survey in order to find out where the gaps in their understanding are. Perhaps you’d prefer to give them a test so that you can check their understanding yourself, or perhaps you’d prefer the students to determine for themselves what they did and did not understand, so you ask students to submit questions about the material. Their questions or their test results could then form the basis of a class session in which you discuss and answer the questions that the students submitted in the survey, or provide further clarification on the things they got wrong in the tests. This approach is often called ‘just in time teaching’ as you don’t really know what you need to cover in class until the test or survey results have been submitted, and this is often less than 24 hours before the class is due to start. If you’d prefer something more student-led then you could still use a pre-class test or survey, but this time you take the students questions (or develop your own questions based around the things they got wrong in the tests) and get the students to answer their questions themselves. This is the approach that Mazur uses, which he terms peer instruction.

“Mazur begins a class with a student-sourced question, then asks students to think the problem through and commit to an answer, which each records using a handheld device (smartphones work fine), and which a central computer statistically compiles, without displaying the overall tally. If between 30 and 70 percent of the class gets the correct answer (Mazur seeks controversy), he moves on to peer instruction. Students find a neighbor with a different answer and make a case for their own response. Each tries to convince the other. During the ensuing chaos, Mazur circulates through the room, eavesdropping on the conversations. He listens especially to incorrect reasoning, so ‘I can re-sensitize myself to the difficulties beginning learners face.’ After two or three minutes, the students vote again, and typically the percentage of correct answers dramatically improves. Then the cycle repeats.” 5

Other options could involve a blend of just in time teaching and peer instruction. These are not the only approaches though, and whilst there is no one correct way of doing things, it’s probably safe to say that an approach which sees the students actively engaged in class is likely to lead to them learning more than an approach in which the students are passive. A visual idea of how the flipped classroom could work in practice is given below:

Waterside – a flipped campus?

Can you flip a whole institution? Yes, you can. Clintondale High School in Michigan started flipping its classes in 2010, and now delivers all classes using the flipped model. They claim that this approach has led to dramatic reductions in both failure rates and discipline problems6. The University of Technology, Sydney, has developed a teaching and learning strategy which fits extremely well with flipped classrooms7, and has set up its own Flipped Learning Action Group to promote the use of this approach8. Does this mean that Waterside going to be a flipped campus? No, it doesn’t. Whilst we won’t have any lecture theatres, and while much of the teaching and learning will happen in smaller teaching spaces (twenty to forty students), a one-size-fits-all approach would not be the best option for the new campus. Nevertheless, what is encouraged for Waterside is what is encouraged at both Park and Avenue campuses here and now, which is participatory, student-led teaching and learning and the use of both class time and technology to engage students in active, exciting and transformative learning experiences.

Will students complain if I flip my classroom?

Possibly. Students may expect lectures and they may think that they learn from them. Students may also like lectures because they’re easy: not much is expected from attendees at lectures as they are “the teaching moment that most promotes passivity and discourages participation.”9 If you adopt a flipped learning approach then students will have to work harder both in class and before class. This is a good thing, and if you want to counter objections from students who want you to lecture you could refer them to bell hooks’ essay quoted above, ‘To Lecture or Not’10, where she tell us that “When we as a culture begin to be serious about teaching and learning, the large lecture will no longer occupy the prominent space that it has held for years.” You could also refer them to Graham Gibbs’ article, ‘Twenty terrible reasons for lecturing’11, in which he explains and provides evidence as to why lecturing does not “give students a rich and rewarding educational experience.”12 In addition, the recent National Union of Students’ publication ‘Radical Innovations in Teaching and Learning’ is worth referring students to as it asked universities to, amongst other things, consider what place the lecture has in “a modern, democratic university.”13

Support for flipping your classroom

What support is available to academics wanting to try out flipped learning? Well, an excellent place to start is with the Learning Designers and the Learning Technology Team. The Learning Designers will be able to explain more about flipped learning, and will be able to help you successfully plan and implement flipped classroom sessions. And the Learning Technology Team will be able to provide you with training and support regarding the technologies that you may want to use as part of your flipped classroom sessions.

To end, it’s worth pointing out that changing the way one teaches takes time, and without support from professional services staff, colleagues and managers, change is not likely to happen. Change, especially radical change, also needs failure to be acknowledged as a possible and legitimate outcome, as not every new technique that we try out will be a success. However, perhaps the flipped classroom offers a low-risk opportunity for change, as there is plenty of training and support available from the Learning Designers and the Learning Technology Team, and the evidence, which we will look at in a later posting, seems to suggest that this is an approach that works.

Contacts

Learning Designers: LD@northampton.ac.uk

Learning Technology Team: LearnTech@northampton.ac.uk

References

1. Parr, C. (2014) ‘Six trends in campus design: 5. Informal, flexible learning spaces.’ Times Higher Education Supplement. December 2014. [online]. Available from: http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/features/six-trends-in-campus-design/4/2017412.article

2. Mazur, E. (2012) ‘The scientific approach to teaching: research as a basis for course design.’ YouTube. [online]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aYiI2Hvg5LE

3. Lambert, C. (2012) ‘Twilight of the Lecture.’ Harvard Magazine. March/April 2012. [online]. Available from: http://harvardmagazine.com/2012/03/twilight-of-the-lecture

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. See: Clintondale High School (2012) Our Story. [online]. Available from: http://flippedhighschool.com/ourstory.php

7. UTS (2104) ‘Learning 2014 Strategy.’ YouTube. [online]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rL0eFmac7mA

8. UTS (2014) ‘Flipped Futures.’ UTS Newsroom. August 2014. [online]. Available from: http://newsroom.uts.edu.au/news/2014/08/flipped-futures

9. hooks, b. (2010) Teaching Critical Thinking: Practical Wisdom. Abingdon: Routledge. p.64.

10. Ibid. pp.63-68.

11. Gibbs, G. (1981) Twenty terrible reasons for lecturing. SCED Occasional Paper No. 8, Birmingham. 1981. [online]. Available from: http://shop.brookes.ac.uk/browse/extra_info.asp?compid=1&modid=1&deptid=47&catid=227&prodid=1174

12. Ibid.

13. NUS (2014) Radical Interventions in Teaching and Learning. [online]. Available from: http://www.nusconnect.org.uk/resources/open/highereducation/Radical-Interventions-in-Teaching-and-Learning/

You might already know that the University has plans to extend our portfolio of high quality blended and online courses. These plans aim to help us meet market demand for flexible, scalable study options, as well as allowing us to bring the campus experience into the 21st century, helping students and staff make the most of valuable contact time. The plans are outlined in more detail in this paper on The University of Northampton’s future online and blended offering, which was approved earlier this year.

In the past few weeks, a key element of this has been put in place with the appointment of Learning Designers, a new role with a remit to help programme teams design effective courses for online and blended learning. The new team is based in Library and Learning Services, working closely with Learning Technologists and CfAP as well as the Institute of Learning and Teaching. Watch this short video to find out more about their role:

(or access the transcript here)

There are three Learning Designers in the new team: Rob Farmer, Rachel Maxwell and Julie Usher. The team will offer a range of design support services, including team CAIeROs and one-to-one support.

Each of the six Schools have nominated priority courses for (re)development, and the team will focus primarily on these in the first instance. If you’d like to find out how the team could support your programme or module, or you have some good practice or learning designs to share, please send initial enquiries to Rob Howe, Head of Learning Technology (rob.howe@northampton.ac.uk).

Last December, Economics Lecturer at NBS, Dr Kevin Deane, took the unusual step of abandoning 4 weeks of his timetabled lecture programme and replacing it with a group exercise culminating in an academic poster exhibition (see this blog posting for more details!)

The exhibition was a real success, particularly for a first-time event, as evidenced by the comments from the students and other NBS staff who attended the exhibition. That said, Kevin has some definite changes and improvements he would introduce next time around. But, in these days of NSS scores and working to improve the student experience, the big question to be answered is … what did the students think?

Generally, their reflections mirrored those of Kevin himself. Apart from an appreciation of the refreshments (!) the following comments are worth mentioning in response to the question of what was good about the task:

- One student responded by saying that the good thing was the “big range of information exchanged and displayed, very insightful. Food was good, getting tutors and guests involved.”

- Another enjoyed the fact that they didn’t have the pressure of an assessed assignment.

- “People did them relatively well. Rewards were good incentive”.

- Another student commented that it “was a great insight into a variety of economists. It provided me with a better understanding of these economists and their philosophies.”

There were some technical hitches on the day of the exhibition itself. In particular, Kevin had been expecting the room to be ready when he and his students arrived, but an error in communication meant that an hour was lost having to set up the exhibition boards. This did have a significant knock-on effect for students as the first hour of the session was lost. This had been scheduled for a student-student presentation of each of the posters, which would have provided the primary opportunity for students to learn about those other economists being studied by their peers.

The following student comments on what could be done differently/better mirror Kevin’s own reflections. Specifically, the students were keen that copies of the other posters were circulated – something Kevin had already planned to do. This is of particular importance pedagogically – where students are creating and generating module content which forms one jigsaw piece of the whole picture, ensuring that each student has access to the full and final picture is essential. Another comment was that it was rightly considered unfair that some students were asked to produce posters on economists that had already been studied in class whereas others were starting from scratch. Looking ahead, Kevin would ensure this didn’t happen again and recognises that it was purely circumstantial, arising from the decision to move away from lecturing to the poster exhibition after the lectures had begun. In itself, this was engendered by student feedback indicating that the lecture approach to this topic was dry and uninteresting.

One final comment worth addressing directly was that students considered the poster to be “too much extra, [it was] not part of our course.” This feedback reflected a failure to appreciate that this poster wasn’t actually ‘extra’ work per se, rather a change in the way the module content was being taught. In future, Kevin would draw attention to the fact that the requirements of producing a poster are no more onerous in terms of the expected study time than indicated in the module spec: 4 students per group x 3 hours per week of independent study x 3 weeks = 36 student study hours per poster.

Other negative comments included the following:

- It was a lot of work, for no obvious reward in terms of assessment.

- Lack of assessment meant no incentive to produce high quality.

- Doing a poster on one subject was limiting.

- Some people didn’t even go.

Having allowed time for both his personal and the students reflections, the following changes would, Kevin believes, improve the exercise next time around:

- Ensuring that the dedicated time for student-student presentations is preserved to ensure that all students receive the benefit of the work done by other groups and learn about all the economists studied in the module

- Explicitly recognise the focus that students place on assessment and grades and therefore turn the task into the first assessment for the module and run it earlier in the academic year when students were not under pressure to complete assessment tasks for other modules

- Ensure that the key points are captured in a summary ‘timeline’ lecture that places them all in context.

Probably the biggest objection he has to overcome is the idea that this task placed an additional burden on students and this really boils down to managing their expectations more explicitly. A clearer explanation and on-going reminder that the poster itself should be the final product of 36 student study hours (9 per student) would go a long way to removing this objection and engendering in students the realisation that this level of work and time investment is, ultimately, what they are at University for!

What do you do when you have a very dry topic to teach and the snores from the lecture theatre are drowning out your words?

Kevin Deane, a new Lecturer in International Development in NBS, faced exactly that problem, some 5-6 weeks into the term. Feedback from the students was clear – “we are bored by this and we are not engaging”. It was time for a radical rethink.

Kevin and I spent about two hours batting ideas back and forth over how to help his class see how the opinions of these long dead men could be relevant to them as 21st century students of economics. I had made a choice not to lecture a group of postgraduate students during a three hour session but instead to spend that face-to-face time on the application rather than the acquisition of knowledge. Could a similar approach be utilised in this context?

The answer came in the form of an academic poster exhibition with each group producing a poster on a different economist which they had to present at an exhibition at the end of term to fellow students and staff within NBS. They also had to explore the relevance of each economist – did they agree with their theories; were their opinions wrong? This had the effect of ensuring a higher level of participation than might otherwise have been the case, given that the poster was not being assessed.

The subsequent 4 weeks of lectures were therefore abandoned and the time allocated to group work on the posters. In spite of some initial discontent Kevin made it clear to the students that this was simply a different approach to teaching and that the students would still be expected to attend and participate. Success was also encouraged by ensuring that students had weekly interim goals and deadlines to work to.

At the exhibition, it was evident that the students I spoke to had engaged with the material and enjoyed finding out about their allocated economist. They had also grasped the concept of what an academic poster was about! A number of staff from NBS were present to ask questions and to help Kevin judge the best poster(s) – three prizes were awarded in the end.

On reflection, Kevin will definitely repeat this approach for this module, but will add an element of assessment to further increase participation and engagement. To read more about the what’s, why’s and wherefore’s, please read his case study – Kevin Deane – Histor.

For now though, this process of resuscitating the wrong opinions of dead men shows that the theories really do live on.

Catherine Fritz demonstrated the concept of flipped teaching – moving assignments into the classroom and delivering lectures as self-paced and scheduled events.

Lectures can be paused by the student to enable research to take place, and give students struggling with vocabulary the chance to look up a word. The lecture is also a much more powerful revision tool. Class work can be more active and collaborative as a result.

The University provides a number of applications to host flipped lectures – Panopto is probably the most suitable, but Kaltura video or NILE based tools like Xerte are also possible delivery mechanisms. In this case Catherine described how Powerpoint can be used to create slides supported with audio. Her presentation contained a step-by-step guide in how to do so.

Powerpoint proved an effective alternative, particularly when access to Panopto is not available. In some respects it is simpler to use than Panopto – amending text on a slide is very easy to do. However, long presentations can result in quite large files which are a problem for some distance learners. Dividing these lectures into sections may well be necessary. As with all asynchronous delivery, support for questions and discussion needs to be available for students at the same time. This will require monitoring, and often moderation, from the tutor.

Overall, this presentation is an excellent example of innovative teaching making used of simple technology and is well worth consideration as an approach. Many thanks to Catherine for producing what is effectively a multimedia instruction manual!

Since the Expo, a new version of Panopto for the iPad has been launched which offers offers a much better recording experience for tutors and an attractive and useful viewing platform for students. It is free to download from the App Store. Ensure you connect to northampton.hosted.panopto.com and login using NILE.

Resources

Original pptx file in ZIP folder, with audio (large file: 33MB)

Flipped Teaching presentation 15th May 2013 – Panopto recording

Flipped Teaching presentation 15th May 2013 – slide summary PDF

Panopto 4.4 release announcement

Further ‘flipped class’ information: blog.peerinstruction.net

Recent Posts

- 15 Years of the Learning Technology Blog!

- Blackboard Upgrade – March 2026

- Blackboard Upgrade – February 2026

- Blackboard Upgrade – January 2026

- Spotlight on Excellence: Bringing AI Conversations into Management Learning

- Blackboard Upgrade – December 2025

- Preparing for your Physiotherapy Apprenticeship Programme (PREP-PAP) by Fiona Barrett and Anna Smith

- Blackboard Upgrade – November 2025

- Fix Your Content Day 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – October 2025

Tags

ABL Practitioner Stories Academic Skills Accessibility Active Blended Learning (ABL) ADE AI Artificial Intelligence Assessment Design Assessment Tools Blackboard Blackboard Learn Blackboard Upgrade Blended Learning Blogs CAIeRO Collaborate Collaboration Distance Learning Feedback FHES Flipped Learning iNorthampton iPad Kaltura Learner Experience MALT Mobile Newsletter NILE NILE Ultra Outside the box Panopto Presentations Quality Reflection SHED Submitting and Grading Electronically (SaGE) Turnitin Ultra Ultra Upgrade Update Updates Video Waterside XerteArchives

Site Admin