By Dr. Jasmine Shadrack, Senior Lecturer in Popular Music, FAST

As this year’s choir have been asked to perform at the opening ceremony of Waterside, as well as our own performance at the Royal next June, it was important to choose a piece of music that had the wow factor. And for me, that has to be Mozart’s Requiem Mass in D Minor. It was the first piece I ever conducted so I have very fond memories of it. I have also performed it myself as a soprano during my undergraduate degree so my knowledge of it is intimate. The fact that Mozart knew he was dying when he wrote it, makes the piece all the more poignant and special.

As this year’s choir have been asked to perform at the opening ceremony of Waterside, as well as our own performance at the Royal next June, it was important to choose a piece of music that had the wow factor. And for me, that has to be Mozart’s Requiem Mass in D Minor. It was the first piece I ever conducted so I have very fond memories of it. I have also performed it myself as a soprano during my undergraduate degree so my knowledge of it is intimate. The fact that Mozart knew he was dying when he wrote it, makes the piece all the more poignant and special.

The music for it will take a longer time to come together but the choir are making great strides already. We have completed (in the most part!) the Aeternam and the Kyrie Eleison (the first two movements) as well as learning some traditional Christmas carols too (for a lunch time concert later in the term). This time I am joined by a new member of staff, Miss Francesca Stevens who does a two hour vocal training session a week to support what I do every Monday in choir rehearsal. Already I have noticed the bond starting to form, not just between each section of the choir, but as a unit too. One of the things I love most about doing this is watching everyone work together for a common goal. It is active blended learning at every stage, from the rehearsals all the way through to the performance. Not only do they learn close score reading, sight reading , close part harmony, how counterpoint functions, effective breathing techniques, good pronunciation, professional conduct and critical listening, they also forge real solidarity as a cohort that spans across all years of the popular music undergraduate degree.

They are able to exercise their own autonomy by using their voice. This might sound simplistic but it really helps to acknowledge that one voice can have a huge impact on a choir. Through their subjective involvement, they take part and contribute to an objective goal so it is experiential. They also gain empowerment through their learning community. As the choir is voluntary, it means that they are there because they want to be and they are not doing it for assessment purposes. I have tried making it assessable previously and it just didn’t work; it actually undermined all the camaraderie and fun we have with it. There is a real sense of inclusivity too that reflects on their personal responsibility to the choir.

So, at week three of the choir in term 1, we are making great progress and having fun at the same time!

Jasmine will be keeping us up to date with the progress of the choir, but this post is also one in a series of ABL Practitioner Stories, published in the countdown to Waterside. If you’d like us to feature your work, get in touch: LD@northampton.ac.uk

By Nick Cartwright, Senior Lecturer in Law, FBL

I was at a meeting of people involved in various ways in staff development of lecturers and as we as an institution had adopted Active Blended Learning (ABL) as the ‘new normal’ I found myself asking in our break-out group: “ABL WTF?” The response was roughly along the lines of “it’s what you do Nick” and several conversations later I was invited to write this blog post about what I do in the classroom and why.

Firstly, one of the most important answers to the why I teach the way I do is because I enjoy doing it this way and it works well for me and what I teach. I certainly don’t think it’s better than other approaches and I don’t know if it would work for every tutor or every subject.

So, I know what works for me now but it was a long journey. I started teaching the way I was taught within the straight-jacket of institutional policy where I then worked, we had a lecture then a seminar every week for ever every module. The lecture was recorded on VHS tapes and stored in the library, the technology meant I had to use PowerPoint and stand stock still behind the lectern. The hour-long seminars I inherited required that in week 1 we asked the students to read chapter 1 of the assigned text, week 2 was chapter 2 and so on. Students were instructed to answer roughly 10 questions and bring hard copies of their answers. I ran a tight ship, students who turned up unprepared were told to leave – my classroom was an exclusive space for the students that were the easiest to teach. We had roughly 5 minutes on each question then left, job done.

Later in my career, at a different institution, I sat in a staff meeting listening to colleagues report that the foundation students had “gone feral” – a chair had been thrown, a lecturer threatened and they simply would not sit down in two straight rows, shut up and listen as wisdom was dispensed. Of course they wouldn’t, despite being bright and capable and having gone through 13 years of formal education they were in the foundation year because they hadn’t achieved the two D’s necessary to enter straight onto the degree programme. Bored with PowerPoint I found myself eagerly volunteering with a colleague to take on these students who we were to later find out were some of the brightest, most enthusiastic students we’d ever had the pleasure of teaching.

One student in feedback tagged our efforts ‘sneaky teaching’ because without realising it they were learning, we tagged it ‘learning by doing’ and at validation the external panel members commended it. In one module the students formed political parties and competed to be elected, in another they witnessed a train wreck and were the lawyers trying to support the victims, at the end arguing before the European Court of Human Rights that one client had the right to die. We didn’t tell them anything, clients sent letters, senior partners sent emails and we patiently waited for them to ask us to direct them to a source or take through a topic area. That we learn best by doing is nothing new, the Ancient Greek philosophers key principle was that dialogue generates ideas from the learner: “Education is not a cramming in, but a drawing out”1. I came to Northampton burning with a passion to get my students learning by doing because it works and because it engages many students who have been excluded by traditional schooling.

One student in feedback tagged our efforts ‘sneaky teaching’ because without realising it they were learning, we tagged it ‘learning by doing’ and at validation the external panel members commended it. In one module the students formed political parties and competed to be elected, in another they witnessed a train wreck and were the lawyers trying to support the victims, at the end arguing before the European Court of Human Rights that one client had the right to die. We didn’t tell them anything, clients sent letters, senior partners sent emails and we patiently waited for them to ask us to direct them to a source or take through a topic area. That we learn best by doing is nothing new, the Ancient Greek philosophers key principle was that dialogue generates ideas from the learner: “Education is not a cramming in, but a drawing out”1. I came to Northampton burning with a passion to get my students learning by doing because it works and because it engages many students who have been excluded by traditional schooling.

I had started out teaching some more practical topic areas so the ‘doing’ was quite easy to work out but last week I found myself in a first-year workshop dealing with the issues of the nature of law and specifically feminist and queer theory approaches. It was when discussing how that had gone that I was asked to write down how I had done it.

The session needed to get the students to grasp that there are different critical voices within (and outside of) feminism and to get to grips with the skill of applying different perspectives to the law – what they applied the law to was less important. The workshop was two hours long and there were three questions to discuss, we ran out of time in every session and every session was completely different. I could have worried about equality of learner experience, ensuring every student in every session got an identical set of correct notes, and in my younger days I would have done, but my students did get equality of learner experience. They got to choose the lenses through which we discussed the issues, for example one group focused on issues of consent and sexual touching in a social setting, another on the lack of diversity in the judiciary and another on whether the dominant narratives around immigration were racist. It was relevant to all of them rather than just those who related to the lens I would have chosen which would likely be white, male and straight.

The session needed to get the students to grasp that there are different critical voices within (and outside of) feminism and to get to grips with the skill of applying different perspectives to the law – what they applied the law to was less important. The workshop was two hours long and there were three questions to discuss, we ran out of time in every session and every session was completely different. I could have worried about equality of learner experience, ensuring every student in every session got an identical set of correct notes, and in my younger days I would have done, but my students did get equality of learner experience. They got to choose the lenses through which we discussed the issues, for example one group focused on issues of consent and sexual touching in a social setting, another on the lack of diversity in the judiciary and another on whether the dominant narratives around immigration were racist. It was relevant to all of them rather than just those who related to the lens I would have chosen which would likely be white, male and straight.

The biggest challenge is letting go and empowering students to find their own way through the issues, generating authentic knowledge which may be different from or even challenge my knowledge. Practically it also involves what I dubbed in chats ‘double thinking’, keeping two chains of thought going at once. One half of my brain is following the students journey, sometimes disappearing down the rabbit hole, whilst the other is focused on what we need to cover and trying to keep an overview of the topic all the time working out what questions I need to throw out to keep the two tracks running in the same direction – if I lose the latter the session suddenly loses any sense of direction and this disengages my students. It’s more challenging and more tiring than how I used to teach, but I believe it is a better, more inclusive experience for my students. I wonder what I’ll be doing 10 years from now and how critical I’ll be of what I do today?

1Clark, D., ‘Socrates: Method Man’ Plan B [online] http://donaldclarkplanb.blogspot.co.uk/search?q=Socrates [accessed 4 October 2013 @ 14:37]

This post is one in a series of ABL Practitioner Stories, published in the countdown to Waterside. If you’d like us to feature your work, get in touch: LD@northampton.ac.uk

Over the past couple of years, lots of different people have asked me about our curriculum change project here at UoN. From teaching staff and students here at the University, to Northampton locals and parents, and even learning and teaching experts at other universities, there is increasing curiosity around the idea of a university without lectures. The lecture theatre has long been an iconic symbol of higher education, heavily featured in popular culture as well as many university recruitment campaigns. So how to explain why we think that we can do better?

Here are some of the reasons why I think that active blended learning (or “you know, just teaching” as I often hear it described), is the way of the future* for student success. What are yours?

- It’s effective for learning. Pedagogic research tells us that it is important for students to be actively involved in their learning – that is, to have opportunities to find, contextualise and test information, and link it to (or explore how it differs from) their prior understanding. Students who construct their own knowledge develop a deeper understanding than students who are just given lots of information, memorise it for the assessment and then promptly forget it. Who was it that said “Tell me and I forget, teach me and I may remember, involve me and I learn”? There is debate about the source of the quote, but there’s a reason it has endured…

- It can be more inclusive. Writers and educators like Annie Murphy Paul and Cathy Davidson are among many who question whether lecturing as a teaching approach benefits some students more than others – or indeed whether the students who succeed most in lecture-intensive programmes are doing so in spite of (rather than because of) the teaching approach. Now, active blended learning is not an easy fix for this challenge, and if not carefully designed it can also create environments that can disadvantage some learners (noisy classrooms can be difficult for students with language or specific learning difficulties, for example, and online environments can be challenging in terms of digital literacy). But with forethought and planning, ABL can help to ensure that all students have a voice and a role in the learning environment, and evidence suggests that it can reduce the attainment gap for less prepared students.

-

It’s more engaging / interesting / fun! When Eric Mazur used Picard et al.‘s electrodermal study to point out that student brainwaves (which were active during labs and homework) ‘flatlined’ in lectures, he may have been at the extreme end of the argument. But from the student perspective, anyone who has been a student in a long lecture (or who has observed rows of students absorbed in their laptops or phones) knows how easy it is to switch off in a large lecture environment. And from the tutor perspective, anyone who has been tasked with giving the same lecture multiple times knows that interaction and contribution from the students is vital to breaking it up. Smaller, more discursive classrooms allow for variety; for more and different voices and ideas to be shared.

- It scaffolds independence. Our students are only with us for a short time. If we teach them to depend on an expert to tell them the answers, what will they do when they don’t have access to those experts any more? The Framework for Higher Education Qualifications says that graduates should, among other things, be able to “solve problems”, to “manage their own learning”, and to make decisions “in complex and unpredictable contexts”. Our graduate attributes say that our students should be able to communicate, collaborate, network and lead. We don’t learn to do these things just by listening to someone else tell us how.

- It recognises how learning works in the real world. Think about the last time you really tried to learn something new. How did you go about it? You may have been lucky enough to have access to experts in that area, but chances are – even if that’s true – you also looked it up, asked some people, maybe tried a few things out. Probably you synthesised or ‘blended’ information from more than one source before you felt like you’d really ‘got it’. To be a lifelong learner, we need to be able to find and assess information in lots of different ways. This is exactly what our ABL approach is trying to teach.

Our classrooms at Waterside may look different to the iconic imagery commonly used to depict the university experience. But maybe it’s about time…

*Looking back on the development of university teaching, there is some debate around how we got to where we are: around what is ‘traditional‘ and what is ‘innovative’ in teaching; and also on whether the ubiquity of the lecture is a result of the economics of massification rather than the translation of pedagogic research into practice. Although it is always good to keep an eye on how practice has developed, I see no need to replicate these debates here – instead, this post is deliberately intended to be future focused, on how best to move forward from this point.

This video from Dr Rachel Maunder, Associate Professor in Psychology, provides some examples of active, blended learning approaches that Rachel has tried in her modules so far. Rachel shares two different models, one which focuses on linking classroom activity to independent study tasks online, and one which includes some teaching in the online environment in addition to face to face sessions. Rachel also shares useful lessons she has learned from her experiences so far.

If you have questions about either of these approaches, Rachel is happy to take these via email.

This post is one in a series of ABL Practitioner Stories, published in the countdown to Waterside. If you’d like us to feature your work, get in touch: LD@northampton.ac.uk

By Samantha Read, Lecturer in Marketing, FBL

Taking an active blended learning approach to the delivery of my Advertising module for the BA Marketing Management Top-Up programme has enabled me to enhance traditional ways of teaching the subject material for students to make constructive links between areas of learning and engage with theory in a fun and collective way.

Traditionally, I presented the students with a lecture-style presentation of the history of advertising, drawing on examples from the past and present to illustrate how advertising practices have changed over time. The subject material by its very nature is fascinating, from uncovering secrets behind Egyptian hieroglyphics to discussing implications of the printing press and debating the impact of the digital environment on advertising. Yet, without the ability to transport students back in time, it felt as if they were not fully able to appreciate the momentous changes that have taken place within advertising over the years.

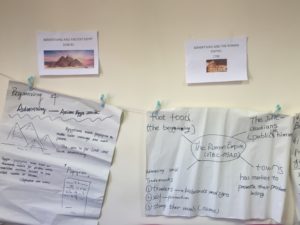

To support the students in learning about the history of advertising this academic year, taking an active blended learning approach, I used a jigsaw classroom technique to facilitate a whole class timeline activity. Before the session, all students were asked to bring in their own device. Following an initial introduction in to the importance of reflecting on the development of advertising over time, I divided the class into seven groups of three or four students. Each group was then given just one piece of the timeline and had 30 minutes to research the implications of that section of history on advertising practice. This included ‘Advertising and Ancient Egypt’, ‘Advertising and the Roman Empire’, ‘The Printing Press was invented’, ‘The development of Billboards’, ‘Radio was invented’, ‘Television was invented’ and ‘The internet was invented’. Students were then given some suggestions of reliable sources where they could go online to research their given time frame and the importance of using these sources and referencing them was stressed.

Whilst the students worked together in their groups to research and construct a one-page A3 poster on flipchart paper outlining their key findings, I circulated the room to check understanding of the research process and the content. This was particularly important as the majority of the students in the class are international students and unfamiliar with UK advertising practices or some terms that they were coming across. I was also able to check the students’ enjoyment of the task and to ensure that everyone in the group was happy to get involved. In contrast to a large lecture style format, the ABL workshop centred on each individual and their specific progression throughout the workshop session.

Upon completion of their A3 poster, each group was instructed to peg their work to the washing line timeline I had attached to the back wall by fitting their time frame within the correct historical period. This ‘active’ jigsaw part of the session not only served a purpose to physically place each time period within its context, but also kept the students engaged in a whole class activity; the success of the timeline ultimately rested with all groups contributing. Once all of the assigned time slots were attached to the washing line, each group selected a member of their group to come to the back of the class to explain their key research findings in relation to the significance of their given time period to the development of advertising throughout history. Having a physical timeline to work with helped sustain the students’ interest in the task and the students themselves were able to make links between each other’s posters, adding to their own and others’ knowledge and understanding.

To ‘blend’ this session to the online environment and subsequently in to the next week’s workshop focusing on the nature of advertising in society, students were asked to complete a survey on NILE which compared print and TV toothpaste advertisements over time. They were also asked to reflect in their online journal on any similarities and differences between the UK based ads included in the survey and those from their home countries. Tutor support and feedback was given on this exercise to ensure that knowledge was accurately embedded and contextualised. Students were also asked to collect three examples of advertisements that they came across over the course of the week as a starting point for a semiotic exercise at the beginning of the next workshop.

Overall, I found the jigsaw classroom technique worked extremely well as part of an ABL approach to teaching the history of advertising. Rather than passively taking in knowledge as I had previously witnessed when delivering this session in the past, there was a real buzz in the classroom. The students were all invested in working together to complete their part of the timeline and were even taking photographs of their completed work. One important aspect of facilitating learning for me is providing opportunities for creativity both in the classroom and online, and taking an ABL approach certainly allows for that.

This post is the first in a new series of ABL Practitioner Stories, published in the countdown to Waterside. If you’d like us to feature your work, get in touch: LD@northampton.ac.uk

Authors: Elizabeth Palmer, (University of Northampton, Learning Designer,) Sylvie Lomer, (University of Manchester, Lecturer in Education) and Ivelina Bashliyska (3rd Year Undergraduate Student and Assistant Researcher).

With thanks to Nadine Shambrooke and David Cousens for support with transcription and coding.

______________________________________________________________________

The University of Northampton has taken an institutional approach to learning and teaching through the widespread adoption of Active Blended Learning (ABL) as its new ‘normal’. To find out more please visit: https://www.northampton.ac.uk/ilt/current-projects/waterside-readiness/

However, student engagement has been highly variable, which has created a number of challenges for staff. Semi-structured qualitative focus groups have been undertaken with 201 undergraduate students across all the year groups and faculties during the academic year 16/17 based on a pilot study of 24 students in academic year 15/16. These focus groups have been looking at trying to uncover the students own perceptions and experiences of ABL in order to unpick the reasons behind varying patterns and engagements and to glean student insight into the factors that inhibit or encourage engagement with ABL.

The study has revealed a number of key factors which students identify as having significant impact on their engagement. Key success factors include effective pedagogical design, in particular establishing a clear and explicit relationship between online and face to face components of modules, and scaffolding the development of digital skills and literacies in the process of establishing online tasks. A strong relationship between staff and students is also critical, where students trust in the decisions and motivations of staff. This is signalled by following up on online tasks, providing feedback where relevant, and explicitly discussing the value of online tasks to module learning outcomes and employability skills. A key finding is that students’ conceptions of learning, teaching & knowledge impact on their engagement with ABL, and are not necessarily compatible with ABL principles. These factors are complex, interdependent and have varying loci of control. Staff can take a number of measures to increase the likelihood of student engagement, although certain factors remain ultimately within the agency of students. Understanding these issues is critical to the success of ABL.

The following artefacts provide the results of the study to date:

Read the Interim Report from the Main Study here:

For Ten Top Tips on how to design ABL to maximise student engagement:

Read the Pilot Study Report here:

Recent Posts

- Blackboard Upgrade – July 2024

- Staff, Student, and PGR Researchers Move From Collaborate to Teams for Online Interviews

- Merged Futures 6 – Interviews

- Evolving student perspectives on Generative Artificial Intelligence at UON: 2024 Report

- NILE Ultra Course Awards Winners 2024

- University of Northampton Students Create New AI Chatbot Prototype

- Blackboard Upgrade – June 2024

- Staff GenAI Survey Report 2024

- Blackboard Upgrade – May 2024

- Learning Technology Team Newsletter – Semester 2, 2023/24

Tags

ABL Practitioner Stories Academic Skills Accessibility Active Blended Learning (ABL) ADE AI Artificial Intelligence Assessment Design Assessment Tools Blackboard Blackboard Learn Blackboard Upgrade Blended Learning Blogs CAIeRO Collaborate Collaboration Distance Learning Feedback FHES Flipped Learning iNorthampton iPad Kaltura Learner Experience MALT Mobile Newsletter NILE NILE Ultra Outside the box Panopto Presentations Quality Reflection SHED Submitting and Grading Electronically (SaGE) Turnitin Ultra Ultra Upgrade Update Updates Video Waterside XerteArchives

Site Admin