Q: How do you eat an elephant?

A: One bite at a time!

The move to Waterside can seem as if it isn’t really that long away, given all that you may feel you have to do inbetween now and then. Wondering where to start can also seem daunting and the mountain of work that you see ahead of you can be so huge that you can’t even see the summit, let alone work out a route to the top.

The move to Waterside can seem as if it isn’t really that long away, given all that you may feel you have to do inbetween now and then. Wondering where to start can also seem daunting and the mountain of work that you see ahead of you can be so huge that you can’t even see the summit, let alone work out a route to the top.

In supporting staff to get to grips with the course redesign implications that are predicated on a number of guiding principles about how learning and teaching will look, the Learning Design team came across a really useful set of blog posts by Tony Bates, a Canadian Research Associate who is also President and CEO of Tony Bates Associates Ltd and who, according to their website are “a private company specializing in consultancy and training in the planning and management of e-learning and distance education.”

The blog posts were written to help people understand and implement a series of practical steps to help deliver quality in their online learning materials. While I don’t wish to duplicate the posts here, I thought it might be helpful to summarise some of the key points in an attempt to help you to start thinking about how you might begin to eat your own elephant, or climb that mountain. I found some obvious points in the posts, some practical and straightforward suggestions and some real gems. There are also some questions and exercises to get you started along the road to redesigning your own modules.

I should also preface this post with the reminders that, as an institution, we are definitely NOT going fully online but will be exploring ways to enhance our learning and teaching using technology and that the precise nature of each blended module is for staff teams to determine.

The Nine Steps are as follows (each link will take you straight to the original post)

- Step 1: Decide how you want to teach online

- Step 2: Decide on what kind of online course

- Step 3: Work in a Team

- Step 4: Build on existing resources

- Step 5: Master the technology

- Step 6: Set appropriate learning goals

- Step 7: Design course structure and learning activities

- Step 8: Communicate, communicate, communicate

- Step 9: Evaluate and innovate

Step 1: Decide how you want to teach online

This step highlights the importance of rethinking the way you teach when you go online and redesigning the teaching to meet the needs of your online learners given that their needs may differ because of the specific learning context. The gem in this post is the emphasis on asking you to consider your basic teaching philosophy – what is your role and how would you like to tackle some of the limitations of classroom teaching and renew your overall approach to teaching? As Bates himself says: “It may not mean doing everything online, but focussing the campus experience on what can only be done on campus.”

This step highlights the importance of rethinking the way you teach when you go online and redesigning the teaching to meet the needs of your online learners given that their needs may differ because of the specific learning context. The gem in this post is the emphasis on asking you to consider your basic teaching philosophy – what is your role and how would you like to tackle some of the limitations of classroom teaching and renew your overall approach to teaching? As Bates himself says: “It may not mean doing everything online, but focussing the campus experience on what can only be done on campus.”

Step 2: Decide on what kind of online course

Bates describes a continuum of online learning ranging from online classroom aids to fully online and explores four key factors that will influence the kind of online course you should be teaching:

Bates describes a continuum of online learning ranging from online classroom aids to fully online and explores four key factors that will influence the kind of online course you should be teaching:

- your teaching philosophy (see step 1)

- the kind of students you are trying to reach (or will have to teach)

- the requirements of the subject discipline

- the resources available to you

A number of subject groups and disciplines are already starting to explore what the current direction of travel for learning and teaching at Northampton might look like for them and developing models and suggestions for how to redesign their modules and programmes within a broader set of principles. It is useful to note that while Bates experience suggests that “almost anything can be effectively taught online, given enough time and money” (emphasis added), the reality is that resources are finite and that it is therefore imperative to work out what could and should be taught face-to-face and what could and should be taught online, remembering that we are still going to be primarily a campus-based institution. He begins the process by differentiating between the teaching of content and the teaching or development of skills and provides a useful example of how this might look in practice.

The gem here is his consideration of how to make best use of the various resources available to you including time (the most precious resource of all), your learning technology support staff (always glad to help), your VLE (NILE) and your colleagues.

Step 3: Work in a Team

Online learning is different to classroom teaching and as a result will require staff to learn some new skills. You are unlikely to have all your F2F learning materials in a suitable format for online learning. This post considers how the team of staff around you can help you to move from where you are, to where you want to get to given that “particular attention has to be paid to providing appropriate online activities for students, and to structuring content in ways that facilitate learning in an asynchronous online environment”. Working in a team can also, of course, help with managing the workload, and with getting quickly to a high quality online standard, as well as being a way to save some of your time.

Online learning is different to classroom teaching and as a result will require staff to learn some new skills. You are unlikely to have all your F2F learning materials in a suitable format for online learning. This post considers how the team of staff around you can help you to move from where you are, to where you want to get to given that “particular attention has to be paid to providing appropriate online activities for students, and to structuring content in ways that facilitate learning in an asynchronous online environment”. Working in a team can also, of course, help with managing the workload, and with getting quickly to a high quality online standard, as well as being a way to save some of your time.

Step 4: Build on Existing Resources

As one Deputy Dean said at a recent School Learning and Teaching Development Day: “Let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater!”

This can include repurposing your own content, but also drawing on existing online resources (TED talks, The Khan Academy, iTunesU) as well as ‘raw’ content that you can use as the basis for developing learning activities and he argues that ‘only in the areas where you have unique, original research that is not yet published, or where you have your own ‘spin’ on content, is it really necessary to create ‘content’ from scratch”.

The hidden gem? Distinguishing between using existing resources that “do not transfer well to an online learning environment (such as a 50 minute recorded lecture), and using materials already specifically developed for online teaching”. He suggests that you “take the time to be properly training in how to use [NILE]”, recognising that a 2-hour investment now can save you hours of time later on.

Step 5: Master the Technology

That’s it really – come to some training on the tools that you would like to use and know more about! This includes learning about their strengths and weaknesses so that you know that you have selected the right tool for the job, but also have a clearer idea about how they might work in practice or how to avoid some of the pitfalls. There are plenty of tools out there, but selecting the right tool is an instructional or pedagogical issue that requires you to be clear on what it is that you are trying to achieve.

Bates’ gem (from my perspective) is his no-nonsense approach to engaging with central training and development initiatives. Here are a few that might help:

- The CLEO (Collaborative Learning Experiences Online) workshop that forms part of our C@N-DO staff development programme is a good way of putting yourself in the shoes of the online learning and experiencing first hand some of the obstacles that online learners face, in order to prevent your own students facing similar issues.

- NILE training (around specific pedagogical purposes) is provided by the Learning Technology team and in addition to regular scheduled training, can also be tailored to suit the purposes of your subject team or discipline. Please just ask!

- Spend a little time each year looking at any of the new features added to NILE during the year (Check out the Learntech Blog for updates).

Finally in this step is a discussion around why simply recording your lectures is not the best way to go. Definitely worth the time to read through his reasons, if this is something you were considering.

Step 6: Set appropriate Learning Goals

In short, should the learning goals (outcomes) for online/blended learning be the same as, or different to the same module delivered in a fully face-to-face mode? The key differentiator is that while the goals may well remain the same, the method may change. He also raises the question as to whether additional learning outcomes need to be considered in terms of the development of 21st century learning skills (in particular, learning the skills to ‘manage knowledge’ long after they graduate).

In short, should the learning goals (outcomes) for online/blended learning be the same as, or different to the same module delivered in a fully face-to-face mode? The key differentiator is that while the goals may well remain the same, the method may change. He also raises the question as to whether additional learning outcomes need to be considered in terms of the development of 21st century learning skills (in particular, learning the skills to ‘manage knowledge’ long after they graduate).

The link between learning outcomes and assessment is also explored here as is the way in which assessment drives student behaviour. He concludes by saying that “[b]ecause the internet is such a large force in our lives, we need to be sure that we are making the most of its potential in our teaching, even if that means changing somewhat what and how we teach”.

Step 7: Design Course Structure and Learning Activities

After an initial exploration between ‘strong’ and ‘loose’ online learning structures, Bates identifies the three main determinates of teaching structure as being:

- the organisational requirements of the institution;

- the preferred philosophy of teaching of the instructor; and

- the instructor’s perception of the needs of the students.

In the light of recent discussions here around what is meant by ‘contact’ hours (see this Definitions paper produced recently by the University’s Institute of Learning and Teaching), he identifies problems with this approach whilst simultaneously recognising that this is, nevertheless, the standard measuring unit for face-to-face teaching. One reason he highlights in particular is that it measures input, not output. Bates is also keen to ensure parity between online and face-to-face learning in terms of ensuring quality at Validation.

He discusses the time input as well as the structure of modules and how existing face-to-face structures mean we can already be some way down the path on module design, with the important proviso that it is important to ensure that content moved online is suitable for online learning. This is where the Learning Design team can help you to make decisions around what to teach or what to leave out, given that making some work optional means it should not be assessed and that if it is not assessed, students will quickly learn to avoid doing it.

This step concludes with a look at how to design student activities. This is typically something that would be covered during the second day of a CAIeRO curriculum redesign workshop, but anyone who has participated in any part of the C@N-DO programme will already have come into contact with some of these online learning activities / e-tivities. Some good points for consideration here though.

Step 8: Communicate, communicate, communicate

This steps explores the vital importance of ongoing, continuing communication between the tutor and the online learners, that is more than simply seeing them in class on a weekly basis. Maintaining tutor presence in the online environment is a “critical factor for online student success and satisfaction”, helping students recognise that their online contributions are just as much a part of their learning experience as the face-to-face components.

This steps explores the vital importance of ongoing, continuing communication between the tutor and the online learners, that is more than simply seeing them in class on a weekly basis. Maintaining tutor presence in the online environment is a “critical factor for online student success and satisfaction”, helping students recognise that their online contributions are just as much a part of their learning experience as the face-to-face components.

Creating a compelling online learning environment is possible but requires deliberate planning and conscientious design. It must also be done in such a way as to control the instructor’s workload. Bates has a number of ‘top tips’ for setting and managing student expectations online and emphasises that tutors should also adhere to these themselves. Like in the CLEO, he suggests starting with a small task in the first week that enables the guidelines to be applied, with the tutor paying particular attention to this activity. As he rightly points out …

students who do not respond to set activities in the first week are at high risk of non-completion. I always follow up with a phone call or e-mail to non-respondents in this first week, and ensure that each student is following the guidelines … What I’m doing is making my presence felt. Students know that I am following what they do from the outset.

There is a discussion here around the benefits and disadvantages of both synchronous and asynchronous communication – the decision again being based on pedagogical need. There is also a list of tips for how to manage online discussions for you to read an inwardly digest 🙂 and a consideration of how cultural factors can impact on participation.

Step 9: Evaluate and Innovate

We ask our students to do it all the time – let’s make sure we apply the same principles to our own learning and teaching development and complete our own reflective cycle. Bates has a series of questions to guide any evaluation of teaching (not just online teaching), linking it back to Step 1 where he defines what we mean in terms of ‘quality’ in online learning. This doesn’t have to be a hugely onerous task – we already have ways of answering some of the questions (e.g. student grades, student participation rates in online activities (track number of views), assignments, Evasys questionnaires etc).

We ask our students to do it all the time – let’s make sure we apply the same principles to our own learning and teaching development and complete our own reflective cycle. Bates has a series of questions to guide any evaluation of teaching (not just online teaching), linking it back to Step 1 where he defines what we mean in terms of ‘quality’ in online learning. This doesn’t have to be a hugely onerous task – we already have ways of answering some of the questions (e.g. student grades, student participation rates in online activities (track number of views), assignments, Evasys questionnaires etc).

Then consider what it is that you need to do differently next time, in this ongoing, iterative process of Quality Enhancement.

Hopefully you will have the opportunity to explore some of these blog postings as you begin to think about how to get ready for Waterside, even if you don’t agree with everything that Bates says!

As Learning Designers, my colleagues Rob, Julie and myself are always looking for ways to help staff with the transition to Waterside and in (re-)designing their modules and programmes to take account of new ways of learning and teaching. To this end, there are a number of posts here on the flipped classroom, or on de-mystifying the CAIeRO for example, that aim to take away some of the apprehensions that we know exist.

As Learning Designers, my colleagues Rob, Julie and myself are always looking for ways to help staff with the transition to Waterside and in (re-)designing their modules and programmes to take account of new ways of learning and teaching. To this end, there are a number of posts here on the flipped classroom, or on de-mystifying the CAIeRO for example, that aim to take away some of the apprehensions that we know exist.

What does teaching mean to you?

Another recent initiative has been a series of activities designed to help staff begin the process of reconceptualising how they teach and articulating their individual teaching style. In the midst of discussions around whether or not we are going to be a fully-online University (definitely ‘not’), or what the ‘new model’ for learning and teaching is going to be (the decision is for you and your team to determine- within certain parameters), it is easy to lose sight of the value of what staff do each and every day in the classroom – our face-to-face contact time (for an understanding of what we mean by ‘contact time’, including face-to-face and online, click here – sign in required). Through conversations with ILT generally and Shirley Bennett, our Head of Academic Practice, we hope to help our staff identify what it is that they value about their face-to-face contact time, and then use technology to help them do more of what they value in the classroom. In starting from this perspective, the aim is to conceptualise technology as an enabler, of excellence in learning and teaching rather than a driver.

In response to the question What do you value about your face-to-face teaching? staff have produced some interesting and sometimes unexpected visual metaphors that will be the subject of a later blog. The workshop/Away Day was also used to set a challenge around learning and teaching innovations through reflectiong on past innovations (to you) and sharing ideas with colleagues.

A 21st Century Learning and Teaching SWOT Analysis

Our Institute for Learning and Teaching have recently produced a short video that many staff may have already seen, showing the general direction of travel for the 2015-2020 learning and teaching plan. It is important to stress that this model is only one approach – if you have an alternative that is more appropriate to your teaching style and your discipline, then there is no reason for you not to explore how that might look in practice.

Our Institute for Learning and Teaching have recently produced a short video that many staff may have already seen, showing the general direction of travel for the 2015-2020 learning and teaching plan. It is important to stress that this model is only one approach – if you have an alternative that is more appropriate to your teaching style and your discipline, then there is no reason for you not to explore how that might look in practice.

The key part of this arrow is the second stage – learning activities that help students to make sense of the content. These can be either online or face-to-face depending on tutors’ individual pedagogy and subject discipline. What works for one subject, might be wholly unsuitable for another – and this is why we are keen to help staff articulate their pedagogical preferences and continue the process of enhancing their own practice and, as a result, the student experience, rather than simply focussing on the latest piece of technology. As a way in to exploring some of these issues, we facilitated a ’21st Century Learning and Teaching SWOT Analysis’. By 21st century learning and teaching, we mean looking at how we prepare our students for employment in the 21st century, where technology is ubiquitous and constantly evolving, and how we use technology ourselves to enhance our learning and teaching. Identifying individual strengths and weaknesses concerning technology-enhanced learning, and highlighting some of the opportunities and threats these new ways of learning and teaching bring helped staff to begin the process of development and provides indicators of individual training needs.

Determining your blend

We also began the process of looking at how to determine what must be taught face-to-face (content or skills) and what could be taught online. Really, this is about thinking what you want your ‘blend’ to look like and builds on the earlier notions of using technology to enable you to do more of what you value in the classroom. Expressing this in terms of what and how students are learning and not solely in terms of what the tutor is teaching can be tricky but we have activities that can help with this. We can also help you to begin to see how this might look in NILE.

Many course teams and individuals have been engaging in various forms of blended learning within their practice for a long time. Determining how you might need to develop your own practices is not something that you need to do in isolation – as Learning Designers, we are here to help and there is also your School Learning Technologist you can draw on, as well as your colleagues.

Packing your Suitcase for Waterside

The day concluded with asking to staff to select what they would need to pack in their suitcases in order to get them from where they are today to where they have identified that they would like to be. This tongue-in-cheek exercise involved selecting from a collection of icons and images of things that you might take on holiday and can include, but is not limited to the following: a bucket and spade (to help you build something new); your Kindle to read while sun-bathing on the beach (mobile content creation and delivery); paracetamol (to help get rid of your headache); lifeguard and buoyancy aid (peer support, learn tech training etc); towel to reserve your (deck)chair (desk) and so on.

The day concluded with asking to staff to select what they would need to pack in their suitcases in order to get them from where they are today to where they have identified that they would like to be. This tongue-in-cheek exercise involved selecting from a collection of icons and images of things that you might take on holiday and can include, but is not limited to the following: a bucket and spade (to help you build something new); your Kindle to read while sun-bathing on the beach (mobile content creation and delivery); paracetamol (to help get rid of your headache); lifeguard and buoyancy aid (peer support, learn tech training etc); towel to reserve your (deck)chair (desk) and so on.

On a more serious note, the underlying premise is to identify your training needs, and other ways in which staff can take steps to ‘get ready for Waterside’ and look at what you might do to respond to the challenges of 21st century learning and teaching or the implementation of Changemaker in the Curriculum.

If you or your subject team would like us to facilitate any or all of these activities at an upcoming Staff Development session or Away Day, or to help you design your teaching to enable you to do more of what you value, please email LD@northampton.ac.uk. You know where we are!

In LearnTech we are regularly asked by academic staff about where to get images for use in NILE, raising questions of copyright and attribution for use of those images.

In LearnTech we are regularly asked by academic staff about where to get images for use in NILE, raising questions of copyright and attribution for use of those images.

Well, perhaps one useful place to start is with the following blog from John Spencer: Eight Free Photo Sites that Require No Attribution. It’s definitely a good place to start with ensuring that you have the appropriate permission to use the images that you have found on NILE, or in your slides.

P.S. The rest of his blog is pretty good too – worth signing up for as he sends out some useful tips and tricks for in the classroom and although generally directed at school teachers, I’ve picked up a few good ideas along the way – including this one 🙂

Following on from the blog post, ‘What is the flipped classroom?’, it seemed that it would be useful to put the ideas discussed there into practice, and to design and build a flipped module in NILE. As you would expect, there is no one way of putting together a flipped module that will work well for everybody – how you choose to design and run your flipped course will depend on a number of things, such as the level of study, size of class, what you enjoy doing in your face-to-face sessions, and what it is that you’re teaching. How you design your course will also depend on what kind of blend you want between the online and the face-to-face teaching elements. For example, if you want to take a two hour a week face-to-face course, and put 50% of the teaching online, this could be blended as a one hour online and one hour face-to-face session every week. However, it could also be done as a two hour online session in week one, followed by a two hour face-to-face session in week two, and so on. You could also rotate the online and face-to-face sessions on a three or four (or more) week basis, or even have all of term one online, and all of term two face-to-face (or vice versa).

The (fictional) course that has been designed and built in NILE has been created with the following in mind:

Title of module: CRIT101: Critical Thinking – A Practical Introduction

Level: 4

Credits: 10

Duration of course: 12 weeks

Contact hours per week: 2

Blend: 50%

Blend type: weekly blend (1 hour online, 1 hour face-to-face per week)

Additionally, the course has been built with the aim that the face-to-face sessions should be highly participatory and focussed as much as possible on dialogue with and between students. Again, this is not necessarily how everyone will want to run their face-to-face sessions – you may prefer to do just in time teaching1, peer instruction2, team-based learning3, problem-based learning4, small-group teaching5, or any number and mixture of other things that you can do in a face-to-face teaching space.

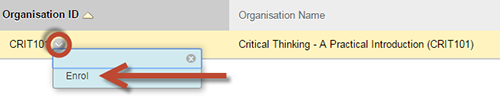

If you would like to find out more, you can enrol yourself on ‘Critical Thinking – A Practical Introduction’ and browse through the materials and the activities. The course begins with a set of three Panopto presentations which introduce the course and the NILE site to students, so this is a good place to begin when looking through the course. To access the course, login to NILE and click on the ‘Sites and Organisations’ tab. Type ‘CRIT101’ in the ‘Organisation Search’ box, and click ‘Go’. You will then see the course listed in the search results. Click on the drop-down menu next to CRIT101, and select enrol (see screenshot below).

The course is fully functional, so feel free to contribute to the discussion boards and take the tests, etc. It’s also very mobile friendly, so works well via the iNorthampton app on iOS and Android devices.

If you have any thoughts on the course, suggestions for improvements, etc., please feel free to respond to this blog post, or to email me directly at robert.farmer@northampton.ac.uk. If you would like to arrange a meeting with a learning designer to discuss what technologies are available in NILE and how you could further develop your own modules, please email LD@northampton.ac.uk.

Notes

1. Just in Time Teaching (JiTT) is a responsive method of teaching in which the content of the in-class sessions is determined by student responses to online activities, often only completed between 1 and 24 hours before the class begins. For more information see: http://www.edutopia.org/blog/just-in-time-teaching-gregor-novak

2. Peer instruction is a method of teaching developed by Eric Mazur at Harvard University in the 1990s. For more information, a good place to start is: http://blog.peerinstruction.net/2013/08/26/the-6-most-common-questions-about-using-peer-instruction-answered/

3. Team-Based Learning (TBL) is an approach to teaching and learning developed by Larry Michaelsen. For more information see: http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/team-based-learning/

4. For more information about Problem-based Learning (PBL) (and enquiry-based and action learning) see: http://www.learningandteaching.info/teaching/pbl.htm

5. A useful guide to small group teaching can be found in Phil Race’s book, ‘The Lecturer’s Toolkit, 4th Edition’ (Routledge, 2015). See, chapter 4 ‘Making small-group teaching work’.

Sister to Qzzr, Pollcaster uses the same account details to create simple ‘one or the other’ type polls. A nice feature is that it collects age and gender information from participants (if they wish to share it – they get to share the results as a reward) and links them to a general (county/state/country) location.

Sister to Qzzr, Pollcaster uses the same account details to create simple ‘one or the other’ type polls. A nice feature is that it collects age and gender information from participants (if they wish to share it – they get to share the results as a reward) and links them to a general (county/state/country) location.

You will need to use the <iframe> version of the embed code in MyPad or NILE – look for the ‘Having Trouble?’ option.

You can find information about other third party tools to incorporate in NILE (including the excellent Storify referred to in an earlier post by Belinda) on the NILEX site

“First Year Education Studies students have been participating in a joint project with students at HAN University in Nijmegen and Arnhem in the Netherlands. An ongoing email correspondence with regard to preconceptions of and stereotyping within England and the Netherlands culminated on Wednesday 25th March with a SKYPE seminar and conversation between students at the two institutions.

Contributions and discussions were lively and both cohorts of students were able to expand on cultural and social traditions in their respective countries. The UoN students will form part of a group travelling on a study visit to Nijmegen in June – it is intended that a meeting with the Dutch students who participated in the SKYPE seminar will form part of their itinerary.” (Tony Smith-Howell)

The students reported that talking with their peers oversees in this way it felt no different from being in the classroom. The tutors are already planning further meetings and online mentoring. They captured their feedback of using SKYPE for the session, via the magic of iPad….. http://www.kaltura.com/tiny/marig

Please contact the Learning Technology Team if you would like to find out more about using Skype for your students.

School of Education Early Years students, led by Dr. Eunice Lumsden, recently engaged in a Tweetchat with students from Sheffield Hallam over two days, using the hashtag #epcrep . This was to respond to the new All-party Parliamentary group report ‘Early Years – A Fit and Healthy Childhood’, which has been co-written with contributions by SoE Faculty, and presented at the House of Lords in March. The Tweetchat was moderated by Dr Damien Fitzgerald, Principal Lecturer. An overview of responses has been created in Storify: https://storify.com/teacheruni/all-party-healthy-childhood-report-our-responses-e Students reported that this was an exciting way to engage, and are keen to continue using Twitter as part of their professional development.

If you would like to explore how to use Twitter for Learning & Teaching, please contact the Learning Technology Team.

Introduction and Rationale

Scott Parker ran a Social Work module using a flipped classroom model and social media in order to stimulate analysis, critical thinking and discussion in seeking deeper learning of themes, topics and issues. One of the key issues underlining this project is that online resources and social media should support the more ‘formal’ teaching process rather than replace it totally.

NILE does have the facility to set up ‘blogs’ or discussion boards’ which can offer similar access to learning materials and opportunities for discussion. However the decision to use Facebook as a platform was an effort to shift the focus from purely academic ‘work’ to a more fluid discussion base beyond the confines of lectures and University based software. Scott points out that clearly there are some caveats within this area of study. There is blurring between the personal and private within user’s lives with potentially risky outcomes, for example; comments can be taken out of context and there is the potential for exploitation of vulnerable users.

Relevance to Practice and lecturing role

The volume of information students need to be exposed to far exceeds the modular structures and ‘contact hours’ stipulated by the Social Work programme, one answer to this is utilising online resources such as Panopto recordings (online video/information dissemination recorded by tutors allowing students to watch at their leisure) to utilise the ‘flipped classroom’ i.e. the online materials are used to ‘set the scene’ and present facts/figures/data etc. With the next face to face teaching session used to assess learning via electronic ‘polls’ or seminar work. This can offer insight into individual student learning/understanding and can serve to direct the focus of onward teaching aimed at deeper understanding and potentially further use of social media to engender peer discussion and debate.

Face to face teaching remains an expectation within a University environment; however this must be enhanced by additional activities and resources to enrich the learning process. Use of social media in teaching may also enhance the collaborative nature of learning; students can discuss/debate issues online and potentially this can include the lecturer, particularly when planning an activity or setting a task for students to complete as part of independent study or group work. This can also support effective reflective practice, illustrating how the ‘original’ theme/discussion item has developed and ideas have ‘evolved’ offering effective feedback for reflection.

Size and structure of Group

The cohort focus was upon level 5 Social Work Students engaging on an Adult Services 20 credit module. Out of a total 35 student in the group it was hoped that at least 20 would consider taking part; in the event 24 participated. Scott was also able to seek feedback from students who declined to participate, particularly with respect to their perceived value of digital/social media to learning.

Emerging Themes

The discussion pages material prompted debate; however students clearly expected more ‘stimulation’ of material by the tutor, despite being informed that the discussion page sought to encourage peer debate and discussion students remarked on how the material and discussion challenged their views and thoughts. This illustrates the overall pedagogic value of enhanced opportunities to offer material in varied and accessible ways in supporting student learning and engagement. Additionally when considering student satisfaction, the module evaluation reported a concurrent level of satisfaction in student expectation, engagement and learning outcomes.

Reflection

There was evidence that uses of a range of ‘external’ resources i.e. those outside the formal teaching or seminar structure, add value to student understanding and learning.

The students who did not participate stated that time was a factor in not accessing the discussion page and clearly this was also true of my role as tutor in ‘stimulating’ discussion, as the project took place during a particularly heavy teaching period; this would have to be addressed in using such methods in the future; possible setting aside a specific time to have ‘live’ discussion, which students could engage directly with and after the ‘live’ session contribute or merely read the discussion dialogue. This could then be used as a ‘starting point’ in seminar sessions to make effective links between module teaching material and wider discussion/engagement.

The project also sought feedback regarding the use of Panopto (video/powerpoint) material to support learning. Generally there was a very positive response to the value of this, which again aims to take the teaching out of the formal lecture theatre/seminar session to an accessible and re-useable format. This suggests a mix of learning tools continues to be appropriate in meeting a diverse range of learning styles and whilst this is time-consuming to prepare, the value to learning and the potential enhanced quality in understanding and engagement with material appears worthwhile.

Anecdotally, it appears that there may have been some impact upon academic achievement as the previous year cohort average module grade was C, whilst this year it was B-. Clearly there may be other factors involved in the improvement of student achievement; however the themes identified in this project suggest that additional resources offer tangible benefits to students.

Click Scott Parker Research Project PGCTHE June1014 – v1 to download Scott Parker’s full report “The use and added value of digital resources and social media in supporting formal learning and teaching at HE level”

Background to the Exchange

Aside from the opportunity to network, my aims in attending the exchange was to examine two main areas – how technology can support the process of innovation and the potential for incorporating System Thinking and Design Thinking into the design of material and even courses. This document summarises my experience and the four lessons I have learned.

Technology and Innovation

Two items on the agenda were particularly relevant here. The MICA Social Design Lab ran during one afternoon – this was a social space designed to encourage interaction between delegates and facilitate discussions, given the question ‘How might we advance social innovation in Higher Education?’

Given the rather spartan conference room environment, the range of fun, brightly coloured physical items to record, connect and visualise responses was attractive and facilitators easy to identify. But while idea capture was strong, collection and dissemination was somewhat weaker. Personally, I never encountered any analysis or results from it, though it may have just passed me by. The physical location hampered the exercise too – delegates could too easily pass by and without their physical presence the exercise was reduced in value. Could technology have supported this process better? Yes, I am convinced it could. At the very least, video or photographic capture needs to be on hand to ensure that contributions can still provoke ideas and actions after the event, along with a clear mechanisim to access it. Ultimately, technologies to engage participants, then capture and disseminate material are essential features of an environment that truly wishes to engage stakeholders. How often has a pile of flip chart paper – containing several person hours of contributions at enormous cost – lingered in the corner of my office?

Lesson #1: Low tech is fun and has its place, but technology to engage in, capture and share group deliberation is essential if the exercise is to make a real difference in a design process.

I attended a session entitled ‘Are we succeeding and how would we know?’, where three case studies were discussing in respect of their attempts to measure success. Drew Bewick of the University of Maryland discussed the use of a ‘Return on Engagement’ grid – very much along the lines of a rubric – to measure the operational value, strategic value and risks of projects on a scale of one to five, and recording the resources used, activities, outputs and impact at the same time.

Lizzie Pollock, from Brown University, discussed the measurement of the learning outcomes for individuals being assessed as part of their Social Innovation Fellowship. The items for inclusion included empathy, creative thinking, critical thinking and entrepreneurial ‘grit’. She was still struggling with ways to evidence and measure these attributes – the Torrance Test, for example, was tried, but rejected on the grounds that it was too broad. Brown are also now beginning to consider – like Maryland – impact, including enterprise survival rates and generated revenue.

John Isham, of Middle bury College, had done some interesting work on the three impact areas of the project itself, the student(s) concerned and the Campus, emphasising the inter-relation of all three. He identified a weakness in project management skills amongst participants in projects and was conscious that just ‘building stuff’ is an inadequate measure of success. Students were beginning to be involved with evaluating other students’ projects but this was at a fairly early stage.

Two points struck me here in particular – the lack of pre-determined project management structures or tools can be a barrier both for students who have little or no experience of managing a project and supervisors who have no ‘dashboard’ view of the progress of a project or its outcomes. Secondly, we seem locked into a ‘new year, fresh start’ approach to developing social innovation projects and ignore the lessons of the previous year.

Lesson #2: A project management system – simple and free to use – is needed to support students and their mentors/supervisors/assessors.

Lesson #3: Evaluation of previous social innovation ventures by students before they start their own, would be a valuable learning experience for them and provide data for the hosting institution.

Systems and Design Thinking

Unfortunately, both sessions related to these topics – ‘Systems Thinking for Leading Changemakers’ and ‘Can Everyone be a Designer? ‘Provocations in the Pedagogy of Design Thinking’ failed to fully deliver to my expectations, the latter being a discussion about a process I didn’t understand! Mary Anne Gobble’s summary article (Gobble 2014) has assisted me to a great extent on the topic of Design Thinking. Whether you believe this to be fad or fact, the importance of taking the “beneficiary’s” perspective into account during the design phase of any social innovation would seem to be a critical success factor.

Lesson #4: Empathy is not just a desirable personal attribute; it is a critical success factor in the design process.

Systems Thinking seems to sit uncomfortably in social innovation design, being apparently more suited to translating the messiness of real life into computer software. However, there are clear connections here to the knotty problem of measuring success – by establishing the ‘units’ that exist within a process flow and their rates of change (along with auxiliary variables) we can begin to pinpoint objective measure of success. Overall, I couldn’t see how a non-specialist could apply these techniques easily, though David Castro did provide some interesting resources and links (including free modeling tools such as InsightMaker) that I may well do some more exploration with.

Summary

Clearly there was a lot more that I got out of the visit, some of which are on http://ashokaun15.weebly.com/. I have an excellent contact in Waterloo, Canada who is sharing her experience of embedding Flipboard into teaching with me, along with the Tophat student response system and met a wide range of contacts from around the world. Many of the delegates leave you speechless at the problems they are seeking to overcome and the relentless enthusiasm they still have to press on. Wrangling with a few NILE issues pales into insignificance when trying to develop a system to support 100,000 students in Indian rural schools with no Internet connection!

But as Wray Irwin pointed out before I left, you would be surprised just how far ahead we are in the field of social innovation compared with most. Developing the support infrastructure for prospective social innovators and evaluating our successes and failures more effectively will push us ahead further still.

References

Gobble, MM. (2014). ‘Design Thinking’, Research Technology Management, 57(3), pp. 59-61

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Tim Curtis for inviting me to attend, Rob Howe and Chris Powis for allowing me to go and the ‘awesome’ support of my fellow delegates in Washington.

(a copy of the fully hyper-text linked version of this document can be found at http://1drv.ms/1FEGoad)

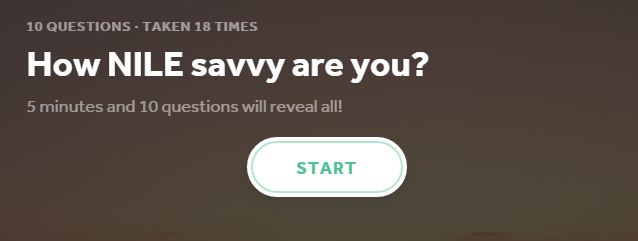

Click the image to start the quiz. It would appear IE9 (installed on UN computers) won’t open this link properly, so please use Chrome or Firefox.

You can find out a bit more about the free tool used to create this quiz in the NILEX site. Quizzes can be embedded directly in NILE.

Recent Posts

- Blackboard Upgrade – March 2026

- Blackboard Upgrade – February 2026

- Blackboard Upgrade – January 2026

- Spotlight on Excellence: Bringing AI Conversations into Management Learning

- Blackboard Upgrade – December 2025

- Preparing for your Physiotherapy Apprenticeship Programme (PREP-PAP) by Fiona Barrett and Anna Smith

- Blackboard Upgrade – November 2025

- Fix Your Content Day 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – October 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – September 2025

Tags

ABL Practitioner Stories Academic Skills Accessibility Active Blended Learning (ABL) ADE AI Artificial Intelligence Assessment Design Assessment Tools Blackboard Blackboard Learn Blackboard Upgrade Blended Learning Blogs CAIeRO Collaborate Collaboration Distance Learning Feedback FHES Flipped Learning iNorthampton iPad Kaltura Learner Experience MALT Mobile Newsletter NILE NILE Ultra Outside the box Panopto Presentations Quality Reflection SHED Submitting and Grading Electronically (SaGE) Turnitin Ultra Ultra Upgrade Update Updates Video Waterside XerteArchives

Site Admin