What?

Through the suggestion of LearnTech Manager Rob Farmer and I were invited/sent along to our inaugural two-day Faculty of Health, Education & Society course development workshop to experience, and hopefully contribute to, the discussion and development of the new Interprofessional Education (IPE) module which was to run for level four students in the 19/20 academic curriculum. Social Work England (SWE) state Education and Training Providers should ‘ensure that students are given the opportunity to work with, and learn from, other professions in order to support multidisciplinary working’ (SWE, 2019:11).[1] It is therefore imperative that all Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) and SWE Health and Social Care programmes demonstrate commitment, delivery and implementation of IPE. However, perceptions of IPE as an additional learning burden for both academics and students alike are problematic and, as such, IPE has to be incorporated into existing curriculums so as not to create a significant amount of extra work for those teaching and studying on professional services’ courses. Therefore, the challenge facing the development team was ‘How can we create a module that can be’:

- Embedded into existing courses

- Self-led for most of the course

- Engaging for students while instructionally effective

To fulfil this brief, we roughly followed the University of Northampton’s CAIeRO[2] process, which is based on the Carpe Diem (Salmon, 2016)[3] design approach; it was decided that the course would be predominantly delivered via self-directed e-tivities. E-tivities combine an online active, participatory experience for individual learners, as well as those working in groups, and facilitates learners to engage with effective pedagogically informed technologies that enhance their digital fluency.[4] The e-tivities developed for the module would incorporate automated, embedded quizzes, to assess and consolidate IPE concepts learned through seminar discussion, and reading and media resources. When considering which educational technology we could deploy, Xerte’s functionality, which encompasses the interactive, self-directed elements of our remit, appeared the obvious choice. Two of three e-tivities would utilise Xerte technology, therefore the CAIeRO team were split into two groups (one led by Liane and one led by myself). Through a creative banging of heads together, the content and design elements for two e-tivity resources were sketched out; I was nominated to go away and, over a three-month period, create the Xerte e-tivity slides.

So what?

Although I had a working knowledge of Xerte, and had used it within my own teaching, the self-directed learning brief meant that I needed to develop slides which promoted this design. The project was interesting in that I had creative freedom to explore and exploit Xerte’s versatility and the range of interactive pages which make Xerte such an effective educational digital tool.

Thus, I was able to embed videos, create multiple choice quizzes, downloadable reflective exercises, and utilise the drag and drop functionality, while the choice of Xerte templates enhanced the presentational style of the finished article making it visually appealing, and professional. However, not all was roses in the Xerte park. The CAIeRO consensus determined that the students should not be able to continue to subsequent pages unless correct answers were given. The multiple choice quiz function did not allow for the checking of multiple answers, which if incorrect, would block the advance of the learner through the slides. Luckily, with the knowledge and expertise of Anne Misselbrook our resident LearnTech Xerte guru, and the wider Xerte community, we were able to source a script which we added to the offending interactive page to produce the desired result.

Technical conundrums aside, it was a challenge to source the relevant content for the e-tivities. Cross departmental input was required, and this took more time than expected, meaning the project overran its projected endpoint.

Now what?

At the time of writing, the level four module is still running, so students’ thoughts and any learning and teaching impact is yet to be evaluated; however, practical improvements for future e-tivity projects can be discerned. Planning and design has to be more focused with concrete content developed pre-e-tivity construction, rather than ad-hoc proposals, which the e-tivity developer has to keep drafting, and re-drafting. As Phemie Wright has identified (2014), “very little research or literature is available regarding practical [learning] design advice” (p.173). As a result of the IPE project, my advice is, don’t just storyboard, have the content ready to go so that developer concentration is focused on the interactivity, and presentation of the design, ensuring the effective production of impactful learning resources.

Salmon, G. (2016) Carpe Diem – A team based approach to learning design. [Online]. Available at: https://www.gillysalmon.com/carpe-diem.html Accessed 04/10/19.

Salmon, G. (2016) E-tivities. [Online]. Available at: https://www.gillysalmon.com/e-tivities.html Accessed 14/02/20.

Usher, J. (2014) De-Mystifying the CAIeRO. [Online]. Available at: https://blogs.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/2014/12/24/demystifying-the-caiero/ Accessed on 14/02/20.

Wright, P. (2014). “E-tivities from the Front Line”: A Community of Inquiry Case Study Analysis of Educators’ Blog Posts on the Topic of Designing and Delivering Online Learning. Education Sciences, 4(2), pp. 172-192. Available at: https://search.proquest.com/docview/1554606873?accountid=12834&rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo Accessed on 04/10/19.

To view an example of the Xerte slides created for IPE, click on the following link:

[1] Social Work England (2019) Qualifying Education and Training Standards 2020. London: SWE.

[2] https://blogs.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/2014/12/24/demystifying-the-caiero/

[3] Rough in that, we loosely applied the 7 CAIeRO stages, but time constraints meant that ideas were never really fleshed out.

[4] See https://www.gillysalmon.com/e-tivities.html for further information on e-tivities.

New look-and-feel for the NILE homepage

June 2020 sees a new look-and-feel for the NILE homepage. While the new homepage is indeed radically different, NILE courses are entirely unaffected. You can read more about the new NILE homepage here:

What is the new NILE homepage for staff

https://askus.northampton.ac.uk/Learntech/faq/230369

What is the new NILE homepage for students

https://askus.northampton.ac.uk/Learntech/faq/230368

New NILE courses for the 20/21 academic year

New NILE courses for the 20/21 academic year will be available for use from the 2nd of June onwards. As usual, the new courses follow the standard template as set out in the NILE Design Standards, so you can create your courses afresh, or you can copy materials from your 19/20 courses into your 20/21 courses. To copy materials across, please follow very carefully our instructions about how to do this:

Bulk copying content between courses in NILE

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-guides/blackboard-learn#s-lg-box-15196768

Full information about finding and setting up your new NILE courses can be found in our FAQ – How do I set up my new NILE course for the upcoming academic year?

https://askus.northampton.ac.uk/Learntech/faq/180655

There are no significant changes to the way that module courses have been created, however, there are major changes to the way that programme courses have been created.

Changes to NILE programme courses

Earlier this year the Student Experience Committee approved changes to the way that programme courses are created in NILE. For many years each programme has had a number of different programme course variations in NILE, which meant that for most programmes there were often eight different variations, and no single course that collected together all students on a programme. From this year onwards there is now a single programme course per programme per academic year, and this course has all students on it who are taking the programme (all years of study, full- and part-time, single and joint honours). This means that a single honours student will be enrolled on one programme course, and a joint honours will be enrolled on both of their programmes courses, plus the joint honours programme course. Foundation students will also have a single programme course for all foundation students.

NILE updates for anonymous marking

As anonymous marking becomes the new normal for the 20/21 academic year, changes in the integration between NILE and the Student Records System mean that you will no longer see students on your NILE courses who have transferred or withdrawn from your modules. The main effect of this is that you can now safely use Turnitin’s ‘Email non-submitters’ tool.

Additionally, and to assist with the process of anonymous marking, the Learning Technology Team have put together the following guides for staff and students:

Anonymous marking guide for staff:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/sage/turnitin_anonymous

Guidance for students submitting work anonymously

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/sage/turnitin-submission/anonymous

Help and support with NILE

As ever, for help and support with any of the NILE tools, or simply to find out more about what NILE is and how the Learning Technology Team can help you, please see our website:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/

And do feel free to contact your learning technologist for advice and guidance about anything related to educational technology in general, or NILE in particular:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-help/who-is-my-learning-technologist

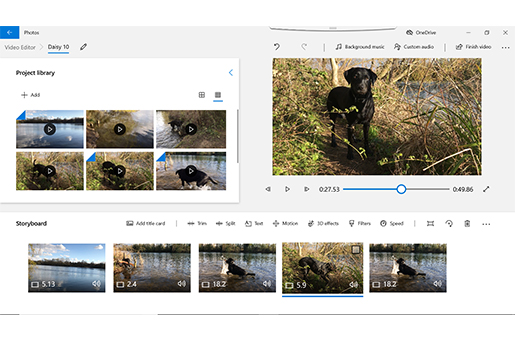

To help support staff in the creation of videos, E-learning/Multimedia Developer Anne Misselbrook and Learning Technologist Richard Byles have launched a new training session which covers the tools available for recording and editing videos.

The virtual webinar session, which lasts 1 and a half hours, covers demonstrations of the ‘Camera App’ and ‘Video Editing App’ tools, and provides information on good practice for creating videos. Staff have opportunities to experiment with these tools and to share their screens with the group.

Anne saw an opportunity for staff to film and edit using tools available, and teamed up with Richard where they developed the course to help staff understand the processes of making films with the tools that are available to hand.

The challenge in developing a session like this before the move to Waterside, was that staff had so many different devices and platforms, but as most staff now have PC laptops with Windows 10 installed they felt the time was right to share their skills.

Feedback has been positive …

“This morning’s session was excellent, easy to follow. Inspired to use the video function, and how to use it effectively. Just need to practice. Thank you. Best Wishes. Krishna Gohil”.

“Thanks. You’re totally right about needing to really think through how to storyboard it in advance, I think that’s much the hardest part. I enjoyed it and I’m looking forward to doing it for a training session. Deborah Forbes”.

“Hello both, I just wanted to say another massive ‘thank you’ for yesterday. Your delivery made what has been a bit of a headache for me so much clearer and very straightforward. Please thank Daisy for her part too! All best, Michelle Pyer”.

“Thanks Anne, really appreciated this session that was conducted by you and Richard. The collaboration and co-teaching were seamless and the content crystal clear. It was great to have an opportunity to attempt an edit during the workshop. This was fun, entertaining and educational – Daisy now has a new fan based on her starring role. Best, Marcella Daye”.

“Thanks for the session I hope it is going to be helpful for the next academic year. Cheers. Noel Harris”.

“Thank you for the video training yesterday – it was a good introduction to the Win10 apps. Thank you, Chris Withers Green”.

Richard said “I think the session works really well. Anne and I can see that the technology has improved so much that it’s now possible for anyone with a mobile device and laptop do go out and make a film. We can share our knowledge of both the practicalities of film-making and the importance of planning, copyright, permissions and accessibility”.

What some people don’t realise is that a lot of work needs to happen before you even turn on the camera. In the session we reveal the process – once you know how it’s done, it all becomes clear.

The sessions began on 29 April and will run until 1 July. More may be planned in the future.

To book a place visit the link here: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/recording-and-editing-video-using-tools-available-tickets-102179561820

Reflecting on being ‘Tech Savvy’

It has come as a really pleasant surprise to be awarded Tech Savvy Lecturer of the Year, especially on the back of my Advancing Equality and Diversity Award last year. More than anything, it means a lot because this is voted for my students, and it is their recognition that really makes the difference for me.

So I’ve been thinking about what it means to be ‘tech savvy’, and I’ve considered the different kinds of tools and systems that have worked for me over the last year. And that brings me to my first reflection – finding a tool that works for you. As we are an ABL-informed campus, I want to use technology in a way that supports and enhances learning, rather than using technology just for the novelty. I’ve tried a lot of different tools over the years, but at the moment, my favourites are:

- Padlet – I really love Padlet as a tool for learning. It acts as a digital corkboard, essentially, and is great for visually capturing thoughts that can inform both in-class and online discussion. Here is an example of one of my favourites, one that I use year-on-year for in-class discussions on gender: https://en-gb.padlet.com/charlotte_dann/gender

- Google Docs – I like collaborative activities, but I appreciate that students like to collaborate in different ways. I have just a couple of examples dotted across my modules where I’ve used Google Docs to capture in-class group work, that we can discuss in live time. As the document is accessible to students, they can come back to this and reflect on it as needed after the discussion too. This is key for me in the use of technology – learning happens outside of the classroom environment, so those activities should still be available to draw on. A favourite example of an effective Google Doc is from my level 6 module Lifespan Development, but was actually based on their assignment rubric – students added their ideas as to what they needed to do to achieve each learning outcome, as organised by grade: http://bit.ly/36f4WYk

- Twitter – I am a lover of social media, though I appreciate it is not everyone’s cup of tea. On top of that, there are so many different platforms now, it’s difficult to decide which would be best to use. I favour Twitter for academic-related content (alongside dog memes), because it provides a short and sharp way of communicating, sharing, and engaging students outside of the classroom. I can share fellow academics papers, start a ‘hashtag’ discussion, or introduce students to other academics they might want to follow for updates. Though not all students use the platform, my profile is not private, so can be viewed without an account. Personally, I benefit from engaging with other academics and sharing best practice on there too. My tip, I guess, would be to find and learn about a platform that would be best for you. https://twitter.com/CharlotteJD

To wrap up, I have to acknowledge how tools are only part of the story in terms of using technology. Any time I want to try something new, or consider use in the classroom (or indeed, online learning) I ask:

- What does engagement look like?

- What is the purpose?

I like to use technology in an interactive way, so I have to consider what engagement looks like, not just for the students, but also for me. If I have a Padlet-related activity for a week, I’ll schedule out time in my diary to check it and give feedback, rather than leave it static. For the social media platforms I use (TikTok has recently taken over my life!) I plan to record and release videos daily, for consistency. And then coming to purpose – if the people that engage with the tools do not understand how it relates to the content, or see a value in it, they won’t use it. I like to make the purpose explicit, linking it to discussions we will have, or to assignments, rather than not revisiting them again.

Overall, technology, and the way we use it, is ever-evolving (even more so, taking our current worldwide situation into account). The more we share and learn from each other – students included!- the better our understanding of what works will be.

There have been some great developments with Microsoft’s Edge browser recently, but we won’t see them on our work laptops just yet.

Edge has been given a complete overhaul under the Chromium project which means that in the long run, the latest version of Edge will potentially work much better with UON’s virtual classroom software, Collaborate Ultra. However, while we work remotely, those developments won’t hit our staff laptops just yet. Blackboard, the company behind Collaborate Ultra, has announced the end of support for the older versions of Edge from the 1st of June 2020 onwards, so now is a good time to start using a different web browser with virtual classrooms if you have not already done so.

The old version of Microsoft Edge has never worked particularly well and LearnTech has always recommended the use of either the Chrome or Firefox web browser. If you have already adopted this recommendation, then please continue as you are but do ensure that you keep your browser up to date to avoid any problems. If you have been using Microsoft Edge on your staff laptop, please move to one of the compatible internet browsers as listed here: Browser support for Collaborate Ultra. The Chrome and Firefox browsers both work especially well, but make sure you keep them up to date for the best experience. If you are using your own Windows computer and are keen to stay with Edge, then you may wish to look at upgrading to the Chromium version of Edge which Microsoft promises a host of improvements: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/edge

Does your computer always open hyperlinks in Edge even when you are working in Chrome? When clicking a web link in an email, for example, it may not open in the browser you wish to use. Changing your default browser will mean that those links open in your intended application. Please see this article from Microsoft on how to accomplish this on a Windows 10 operating system.

As always, please contact your learning technologist if you have any questions.

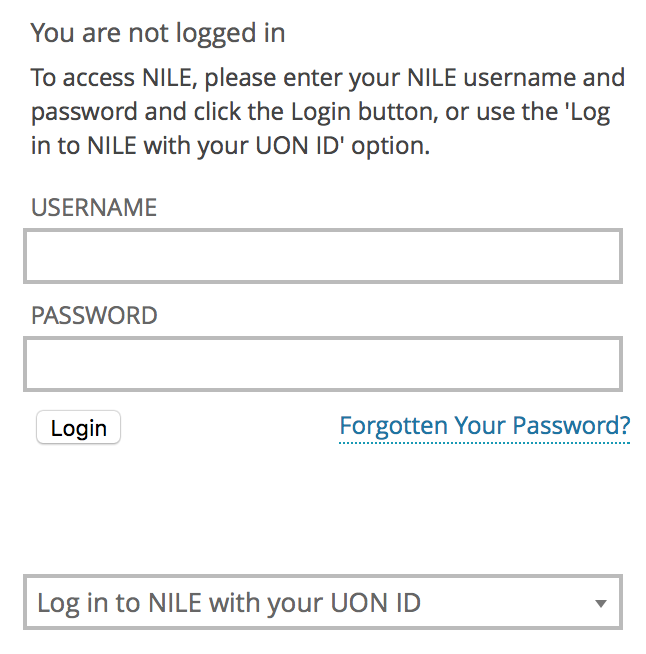

As part of our work improving and updating NILE, we are making some changes to the way that you log in to NILE, with the aim being to make accessing NILE both simpler and more secure.

You will still use your current University of Northampton username* (your student number, or staff ID) and password to login to NILE; these will not change. In fact, most of the changes will be made behind the scenes as we upgrade to the latest and most secure method of authentication, but there are one or two changes that you will notice.

Firstly, once you have logged in to the Student Hub or Staff Intranet** you will no longer have to log in to NILE again. Just click on the NILE link, and you’ll be taken directly into NILE without having to enter your username and password again.

Secondly, if you access NILE directly via nile.northampton.ac.uk, then for a limited time you’ll see that you have two login options. You’ll have the regular username and password option, but you now also have an option to use the new ‘Log in to NILE with your UON ID’ option. If you prefer to access NILE directly, rather than going via the Student Hub or the Staff Intranet, we encourage you to start using the new ‘Log in to NILE with your UON ID’ option.

When you use these new NILE login options, then when you come to log out of NILE you’ll see that you are presented with two choices: you can either log out of NILE only (which logs you out of NILE, but keeps you logged in to other University systems, including the Student Hub, Staff Intranet, and your University Office 365 and OneDrive accounts, etc); or you can securely log out of NILE and all University systems at the same time.

*Your University username will be in one of the following formats:

- Students: this is your 8 digit UON student number;

- University of Northampton Staff: this is your UON staff username, usually comprising your initial(s) and the first few characters of your last name;

- Staff working at partner institutions: this is your ARMS account ID, and is an 8 digit number beginning 999.

**Please note that only University of Northampton staff can log into the Staff Intranet. Partner staff will always need to access NILE by going directly to nile.northampton.ac.uk

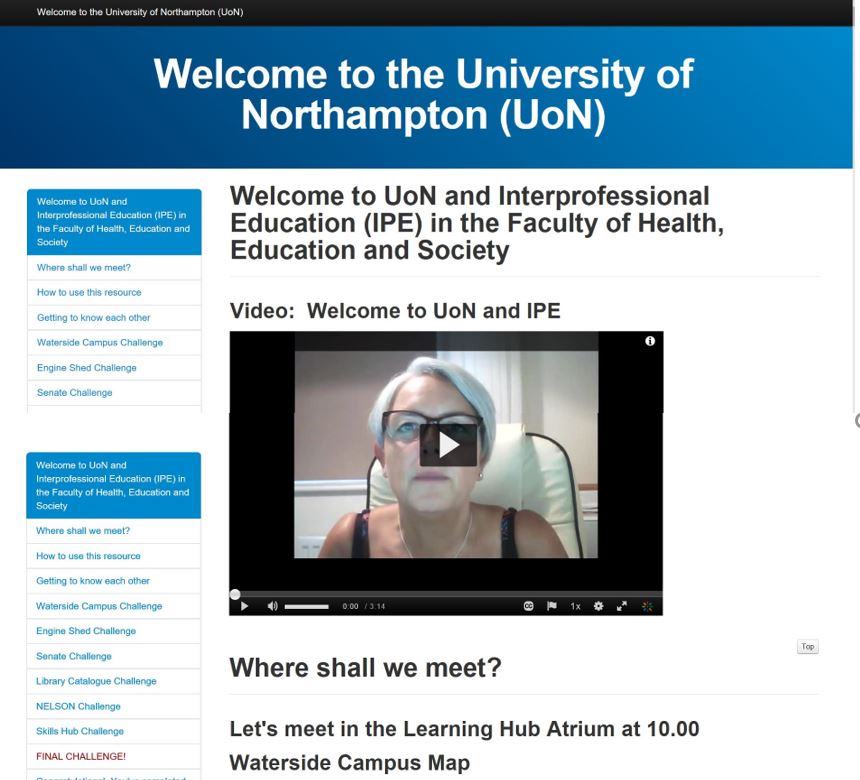

As Faculty Lead for Interprofessional Education in the Faculty of Health, Education and Society, I needed to create a resource that students could engage with on day two of their programmes – meaning it had to be user-friendly and accessible to students with a range of IT skills. Having previously tried NILE, I found that this was far too early to introduce it as a synchronous learning tool as students were unfamiliar with the VLE and its tools for working collaboratively. When discussing my dilemma with Rob Howe, he suggested I try Bootstrap xerte and set up a meeting with Anne Misselbrook as the University’s ‘guru’!

After a short walk-through I had a go at creating my xerte and found the process to be very straightforward (after a minor issue with formatting that Anne was quick to support me with). The end product looks professional and user-friendly – I’m delighted with it and look forward to hearing future students’ feedback on its accessibility. I aim to use Bootstrap xerte in the near future for creating a resource for anatomy and physiology and in the current climate can see it as an excellent platform for developing online resources that look professional and are easy to navigate for the student.

If you’ve unexpectedly found yourself in the midst of a terrifying global pandemic and have been told that you will now be delivering all your classes online, then you may find one or two things in this blog post that will help you.

1. Which tool(s) should I use for online teaching?

In the world of online teaching, you will often find people referring to synchronous and asynchronous tools. All this means is real-time, or not. Synchronous tools are real-time online tools, and are those that are used instead of a face-to-face classroom session – they allow people to interact online with one another in real time: think Skype, or Facetime, or just being on the phone with someone. Asynchronous tools are those that are used when people can interact as and when they have time – they do not typically require an instantaneous response: think email, or text messaging, or simply writing letters.

At the University of Northampton, your synchronous teaching and learning tool of choice is Blackboard Collaborate Ultra. It is the University’s virtual classroom tool, and has been part of NILE and enabled and available in your NILE sites for a few years now. If you are moving a face-to-face class online it is highly probable that you will want to use Blackboard Collaborate Ultra (hereafter simply Collaborate). Asynchronous tools are a little more varied, but given the current situation let’s keep it simple and say that unless you have a better idea (which is perfectly possible), Blackboard’s Discussion Board tool is your asynchronous tool of choice.

The University’s Learning Technology Team will support you to understand and use these tools, both from a technical and a pedagogical perspective. However, as you will appreciate, they’re pretty busy at the moment, so here are a few things that may help you out while you’re waiting for a response to that email you just sent them.

What you need to know about Collaborate

Collaborate is already in all of your NILE module site(s) – each and every one of them. You don’t need to do anything to start using it with your students, apart from making the ‘Virtual classroom’ link available (which is covered in the staff Collaborate guide).

There is guidance on using Collaborate for staff and students available here:

Collaborate Guide for Staff

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-guides/blackboard-collaborate

Collaborate Guide for your Students

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/students/nile-guides/blackboard-collaborate

What you need to know about Discussion Boards

Discussion Boards are also already activated and available in your NILE site(s). You may want to use these in between Collaborate sessions in order to facilitate class discussions in the days or weeks in between classes.

If you’d like to know more about Discussion Boards (and Blogs and Journals too), you’ll find this guide useful:

Blogs, Journals and Discussion Boards – A Guide for Staff

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/sage/blog-journal-discussion

2. What happens with assessments online?

For the most part, coursework assessments will be able to continue normally. However, if your students were due to take an in-class test then this is going to be a problem.

A good option here is to consider making your in-class test into an open book or take home exam. It may be the case that with minor modifications your in-class test paper can be revised to work well when students are at home with access to their books and to the Internet. You may also consider giving students a longer window in which to take the exam – if you’ve not thought about using a 24 hour exam before then perhaps this is the time to try it out!

If this appeals, then then the best way to put it into practice is to release your open book/take home exam paper on NILE at the point at which the exam begins, and to setup a Turnitin submission point with a submission due date/time for the end of the exam to collect the papers in at the end (make sure it accepts submissions after the due date though, as some students may be allowed extra time). Most students are familiar with using Turnitin by this point in the year, and Turnitin’s text matching feature will deter collusion and plagiarism.

Full guidance on setting up and using Turnitin is available on our website at:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/sage/turnitin

3. Do I have to teach differently online?

Online teaching is certainly different from face-to-face teaching, but many, if not all, of the principles of good teaching apply regardless of whether you are teaching online or face-to-face.

One of my favourite books about teaching is Ken Bain’s What the Best College Teachers Do (2004). In a study entitled What the Best Online Teachers Should Do, which was conducted a few years after Bain published his book, a group of teachers tried out Bain’s recommendations in the online teaching and learning environment. While they found that online teaching was different to, and, sometimes, more difficult than, face-to-face teaching, the three key principles of ‘good teaching’ applied both in the online and in the face-to-face teaching worlds. In a nutshell, these principles are:

Principle 1. Foster student engagement

“Bain (2004) asserts that the best college teachers foster engagement through effective student interactions with faculty, peers, and content. They see the potential in every student, demonstrate a strong trust in their students, encourage them to be reflective and candid, and foster intrinsic motivation moving students toward learning goals.”

“In the online environment, lecture need not and should not be the primary teaching strategy because it leads to learner isolation and attrition. The most important role of the teacher is to ensure a high level of interaction and participation … student engagement with teachers, peers, and content is vital in the online learning environment.”

Principle 2. Stimulate intellectual development

“According to Bain the best teachers create a natural critical learning environment. … when it comes to stimulating intellectual development in students, questions are the key to creating a natural critical learning environment … Questions are universal; they can be asked and answered anytime or anywhere. They work best when the students ask them or when the students find them interesting. As long as it is possible to ask questions in an online class, then Bain’s natural critical learning environment can exist in an online class.”

Principle 3. Build rapport with students

“One way that Bain identified highly effective teachers was by how they treated their students. He recognized that such teachers ‘tend to reflect a strong trust in students. These teachers usually believe that students want to learn and they assume, until proven otherwise, that they can.'”

” … when it comes to building rapport with students, the best online teachers should understand the characteristics of their students and adapt accordingly … An important element of rapport building is that teachers are flexible – with regard to getting to know their students, getting their students to know them, working around deadlines, and creating an atmosphere that enhances learning.”

And if those three principles sound pretty much like what you’re doing already in your regular face-to-face classes, that’s probably because they are! So maybe online teaching is not too different from face-to-face teaching after all. While the environment is certainly different, the aims and principles of good teaching remain the same.

NB. All the above quotes are from Brinthaupt, T. M., et al., (2011) What the Best Online Teachers Should Do. Merlot Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 7(4). Available from: https://jolt.merlot.org/vol7no4/brinthaupt_1211.htm

4. Where can I get more help and support?

There is more help and support available about all aspects of technology-enabled teaching and learning from the Learning Technology Team.

You can find lots of information about NILE and about the various digital tools available to you and your students on our website:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech

You can take our online, self-study NILE training course:

https://mypad.northampton.ac.uk/niletrainingewo/

If you are a member of staff at the University of Northampton you can also get more help from your learning technologist:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-help/who-is-my-learning-technologist

If you are a member of staff at one of our UK partner or international partner organisations, you can get more help from the NILE champion at your institution:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-help/partners-nile-champions

The University of Northampton’s chosen software for virtual classrooms, Collaborate Ultra, is deployed by the vendor Blackboard via a ‘software as a service’ method (SaaS). One major benefit of this deployment method is that users receive improvements soon after they are developed and released by the company, which can be as frequently as every month. Other software deployment methods can leave users waiting for annual or bi-annual major releases.

Below are details of two minor-but-useful feature updates scheduled for release on 12th March. LearnTech hope you enjoy these new features. If you have any questions, please get in touch.

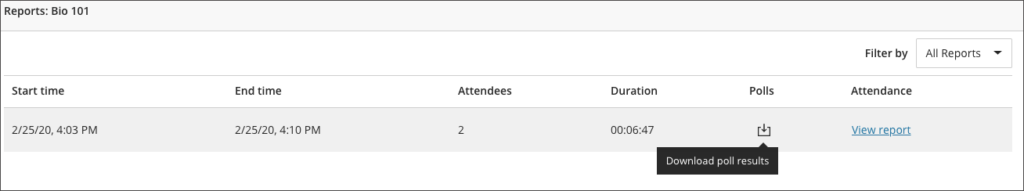

Download poll results

Anyone making use of the polling feature with their students or attendees will be able to download a report after the session. The report includes the poll question and how each attendee responded. It will be available to moderators and instructors from the same location as the attendance report.

Whiteboard updates

The use of a whiteboard in the virtual environment continues to improve for all users. This very minor update makes it easier to select and rotate individual items, removing frustration for those users who like to be a little more creative with the content editing tools on the whiteboard.

Perhaps an unruly dog ate a student’s earbuds and there’s your essential video lecture on Ethical Engineering they simply have to watch in the jam-packed silent carriage of the 8:50 from Leamington Spa. In this all too common circumstance captions are key.

What if you have an especially grating tone and listening to you might drive your students mad and you fear they might explode? Captions could well save the day.

Maybe they are unable to hear sounds or find it difficult listening for long periods and so want a transcription to peruse at their own pace. Students undoubtedly love your educational videos but sometimes you mumble, sometimes you drone and at times you rattle along with such fury you sound like you’re being hunted by assassins.

Captions can be the solution to many physical, practical, social or emotional situations. In fact, students can expect video captions for any good or silly reason and of course you would want the captions to be there just when they need them. You’d not expect them to make a special request. Nor would you force them to fill out endless forms justifying why, for heaven’s sake, they could possibly want captions. It’s not an unreasonable request. They’re not demanding the hour-long presentation on 18th century macroeconomics is transcribed into semaphore, are they? Now, that would be a stretch. No, video captions are not an eccentric request in these modern times with cinematic teaching so twenty-four everywhere.

And so, we at the University of Northampton provide machine-generated captions for each and every one of your video masterworks sat on our MediaSpace platform. Hurrah, you yell inwardly in the slowly shuffling lunchtime queue. But hold your horse! Machines are, in many ways, remarkable but in other ways they are, like many a politician or pig, decidedly lacking in wisdom, wit or common sense. Captions are one such area where machines often fare poorly.

Consider an average video about a common subject, like making a pot of tea. How does a machine make sense of the clear instructions provided by the skilled and softly-spoken tea-maker? Utter gobbledegook, dear reader or listener. The machine’s algorithm struggles with even the simplest step. How does the mighty machine transcribe the modest instruction of leaving the tea-bag to sit in the pot and brew?

“Leave the tea bark in the pottery and lettuce prove.”

Ridiculous twaddle.

And so, in truth, though you may have many videos in your MediaSpace account with automatically-generated captions, the understanding of this machine-made text can be like tumbling headfirst into word casserole. A linguistic hell for those with a dyslexic mind or for that matter anyone with a passing knowledge of the English language.

A potential calamity.

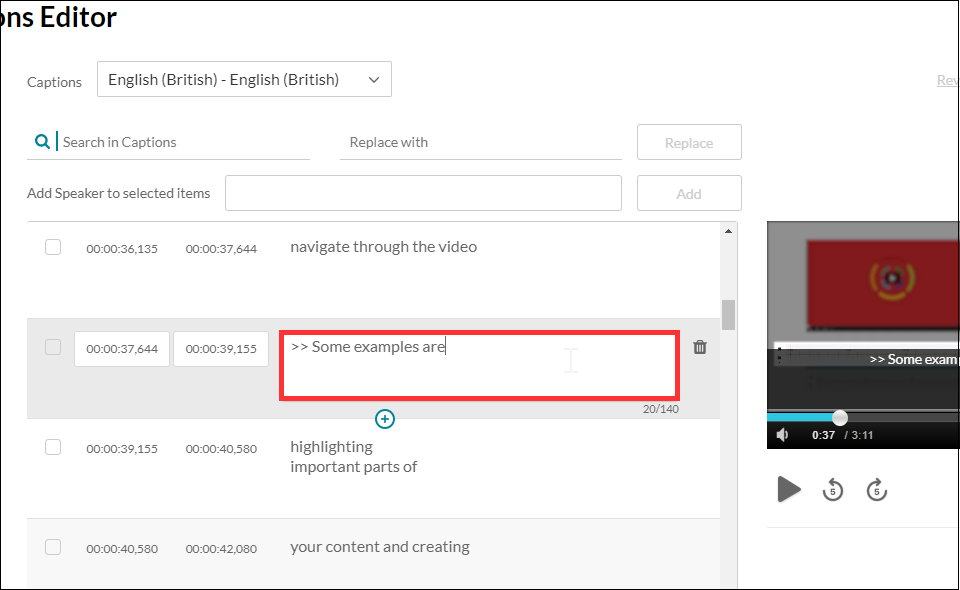

Thankfully, one solution is provided in the form of a simple caption-editing interface. This electronic instrument enables the gentle presenter to easily tweak the nonsense generated by the machine or equally the nonsense generated by the presenter themselves.

I should also point out if a student has a specific need for captions, you can ask for a human being of immense skill and dexterity to write the captions manually with the machine as a mere assistant to the process. Thankfully, this service does not require any form-filling nor nosey interrogation but is instead founded on unconditional trust and the belief it is not merely a trick on the part of the video author to avoid undesirable finger-strain.

So, in the concluding stage of this somewhat rambling essay can I offer my modest advice on some good practice, if you’re to provide captions to your audience with the least amount of extra work. Academic life is ordinarily bursting with work, so to add more without need is surely a woeful circumstance.

My first tip is to be clear.

Be clear in both in diction and in content. That is to say, don’t mumble or speak with your mouth full, as all good children are taught. Don’t assume your audience has the faintest idea what you are talking about. Don’t assume your audience even cares what you’re talking about. Sure, they may need to understand the knowledge you are trying to transfer but don’t confuse that with thinking they want to listen to you. If this is about knowledge transfer and not a fascinating fireside yarn of monsters and magic, then be clear. If, of course, your video is precisely a story of monsters and magic, accept my earnest apology and kindly share the link as I am exceptionally partial to such tales. This leads me to my second and mercifully final piece of advice.

Keep your video short.

Surely an irony coming from one such as I, able to spin a lengthy yarn from such meagre thread? Like the best party food, learning is sometimes best consumed in small bites and if you cannot keep it short, then please keep it engaging. Tell a story. Your audience may forgive you if your story interests them, but a limp string of facts is no better than a shopping list. Be clear and be interesting and your video captions will sing.

Now, go on your way and teach the world to sing.

Recent Posts

- Blackboard Upgrade – March 2026

- Blackboard Upgrade – February 2026

- Blackboard Upgrade – January 2026

- Spotlight on Excellence: Bringing AI Conversations into Management Learning

- Blackboard Upgrade – December 2025

- Preparing for your Physiotherapy Apprenticeship Programme (PREP-PAP) by Fiona Barrett and Anna Smith

- Blackboard Upgrade – November 2025

- Fix Your Content Day 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – October 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – September 2025

Tags

ABL Practitioner Stories Academic Skills Accessibility Active Blended Learning (ABL) ADE AI Artificial Intelligence Assessment Design Assessment Tools Blackboard Blackboard Learn Blackboard Upgrade Blended Learning Blogs CAIeRO Collaborate Collaboration Distance Learning Feedback FHES Flipped Learning iNorthampton iPad Kaltura Learner Experience MALT Mobile Newsletter NILE NILE Ultra Outside the box Panopto Presentations Quality Reflection SHED Submitting and Grading Electronically (SaGE) Turnitin Ultra Ultra Upgrade Update Updates Video Waterside XerteArchives

Site Admin