Whether you use a browser or an installed app (for any product), it is essential that it is kept up to date in order to provide you with the most up to date and secure experience. Previous blogs have noted that if you have been using Microsoft Edge on your staff laptop then you should move to one of the compatible internet browsers as listed here: Browser support for Collaborate Ultra. The Chrome and Firefox browsers work especially well, but you will need to keep them up to date for the best experience.

Keeping browsers up to date is normally a straightforward process as they will update themselves automatically or be updated by the institution (if your laptop is managed by them). The problem comes when you machine is managed by the institution but you have not connected to their network for several months – its easy for the software to get out of date and not respond correctly……..or stop responding at all!

To check if you have the most recent version of Chrome then please have a look at steps below:

- On your computer, open Chrome.

- At the top right, click More

.

- Click Help

About Google Chrome.

The current version number is the series of numbers beneath the “Google Chrome” heading. Chrome will check for updates when you’re on this page.

To apply any available updates, click Relaunch.

If you are unable to update Chrome then please contact IT Services for support (01604 893333) or log a case for them to check.

IT have also noted that some personal staff and student devices have security set so high on their devices that it will block access to the microphone and webcam but not necessarily show any error / warning messages. This does not mean that the device will always be sharing camera and microphone but means that it will fail any check which see if it is possible to do this. For those using Windows 10 then please see this guide from Microsoft which provides instructions on changing the settings.

If you’d like to run a quick self check to see if the browser is running correctly then Blackboard have provided a browser checking tool.

What is UON Ultra?

UON Ultra is a five-year project to migrate the University’s Virtual Learning Environment (VLE), NILE, from Blackboard Learn Original (hereafter Original) to Blackboard Learn Ultra (hereafter Ultra). The purpose of moving from Original to Ultra is to ensure that the University is using a modern VLE that is intuitive, mobile friendly, device agnostic, responsive, and accessible: i.e., a VLE that best supports our students and our mode of teaching, and which works equally well regardless of whether it is accessed via a desktop, laptop, iPad, etc., or smartphone.

Who will the project impact?

Original is the University’s digital campus and has been used at Northampton since 2002. Original is embedded in all aspects of teaching and learning at the University: it is where online teaching and learning takes place; where online learning activities are engaged in; where teaching and learning materials are made available to students; and, since 2012, is where almost all students’ assignments are submitted, and where students receive their assignment grades and feedback. The project will therefore impact all University students and all academic staff at the University and at partner institutions.

Who are the project delivery team?

UON Ultra will be delivered by the Learning Technology Team, in conjunction with academic staff from across the faculties.

What are the key dates and milestones for the project?

UON Ultra will be delivered in five phases over five academic years, starting in late-2019 and ending in summer 2024. The delivery timescale has been chosen and approved by UMT to ensure minimal impact to students who are used to Original, and to allow staff as much time as possible to get used to working with Ultra.

Phase one – 2019/20

• October to December 2019: Blackboard Original Managed Hosting (MH) to Software as a Service (SaaS) migration planning and testing.

• December 2019: Migrate all Original environments (Production, Staging, Test) from MH to SaaS.

• January 2020: Upgrade Original to Ultra Base Navigation (UBN) on Test.

• February 2020: Design and deliver pilot course EDUM129 via Ultra on Test.

• May 2020: Upgrade Original to UBN on Staging.

• June 2020: Upgrade Original UBN on Production.

• June to September 2020: Recruit participants to Ultra pilot project and design modules (approx. 10) for Ultra delivery from September 2020.

Phase two – 2020/21

• September 2020: First teaching of pilot Ultra modules.

• September 2020: Creation of test Ultra courses for all Level 4 modules.

• From September 2020: Ultra training for academic staff. Subject areas to receive bespoke training from their learning technologist.

• September 2020 to August 2021: Design of level 4 Ultra courses by academic staff (with support from the Learning Technology Team).

Phase three – 2021/22

• September 2021: First teaching of all Level 4 modules via Ultra.

• September 2021: Creation of test Ultra courses for all Level 5 modules.

• From September 2021: Continuation of Ultra training for academic staff. Subject areas to receive bespoke training from their learning technologist.

• September 2021 to August 2022: Design of level 5 Ultra courses by academic staff (with support from the Learning Technology Team).

Phase four – 2022/23

• September 2022: First teaching of all Level 5 modules via Ultra.

• September 2022: Creation of test Ultra courses for all Level 6/7/8 modules.

• September 2022 to August 2023: Continuation of Ultra training for academic staff. Subject areas to receive bespoke training from their learning technologist.

• September 2022 to August 2023: Design of level 6/7/8 Ultra courses by academic staff (with support from the Learning Technology Team).

Phase five – 2023/24

• September 2023: First teaching of all Level 6, 7 and 8 modules via Ultra.

• September 2023: First use of Ultra programme-level courses.

Where can I find out more about Ultra?

The Learning Technology Team will, of course, provide plenty of bespoke training on Ultra from September 2020 onwards, but Blackboard have also created training and support materials about Ultra which you can access.

Blackboard’s LearnUltra site contains a lot of information about Ultra and explains the benefits of using it: https://learnultra.blackboard.com/

Blackboard Ultra Training Videos: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLontYaReEU1tCbsCDP-u_wsKdkDBegIhH

Any questions?

If you have any questions about the UON Ultra project, please contact the Head of Learning Technology, Rob Howe, at rob.howe@northampton.ac.uk

On the 21st May as part of Global Accessibility Day, Charlotte Dann and Jean Edwards took up the challenge to improve the accessibility of their NILE sites using the Ally tool.

The challenge involved using the Ally module accessibility reports (https://askus.northampton.ac.uk/Learntech/faq/189667) to incrementally make changes to their course which would make their course more accessible and ultimately make their courses more accessible to students. The intrepid tutors worked during the day to make the necessary changes and improve Northampton’s score on the global league table:

By the end of the day, Northampton finished 28th in the World (3rd in Europe) for the greatest improvement.

Congratulations to Charlotte and Jean.

For more assistance on using Ally then contact your Learning Technologist – https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-help/who-is-my-learning-technologist

One of the benefits of the University of Northampton’s membership of ALT is that any member of staff is entitled to sign up to free Associate Membership. This will entitle you to find out about news and opportunities in the wider world of Learning Technology.

All you will need to do is complete the sign up form.

For those wanting to take the membership to the next stage then Certified Membership of ALT is also possible. This involves completing a reflective portfolio which is then assessed.

Feel free to chat to Rob Howe (Rob.Howe@northampton.ac.uk) if you want more information.

All Northampton material must be accessible to everyone who needs it. If it isn’t, the content owner / University may be in breach of the Equality Act 2010 (see Appendix A) and the Public Sector Bodies (Websites and Mobile Applications) (No. 2) Accessibility Regulations 2018.

This means we start thinking about how users might access and use content and systems before we design or build anything.

Accessibility isn’t the responsibility of just one person. Everyone involved is responsible for making sure the service is accessible. Training is available to all staff to ensure they are able to recognise their responsibilities and create accessible content.

- If you have material on NILE then make use of Ally to help you improve the accessibility of content.

- If you produce any material which is viewed on the web then please follow the University guidance which is under the brand element of the MIR pages.

- If you are just starting with producing web based content then attend the training on creating accessible online content (Full details below):

Improving your knowledge of creating accessible online content.

During this one-hour essentials course, you will learn easy and practical steps to ensure your online content – documents, attachments, files, videos, animations and web copy – is accessible to anyone who needs it.

- To view dates and register for this training, please visit HR Self Service > navigate to the Course Catalogue > search for Creating Accessible Online Content.

- If you need help using the Staff Development function in U4BW please see the short user guide.

This post brings together some of the useful updates from the team which have been posted in the past few months.

NILE related

Guidance on setting up your new NILE course for the upcoming academic year?

NILE Quality Standards – What should be included in every NILE site

What is the new NILE homepage for staff

https://askus.northampton.ac.uk/Learntech/faq/230369

What is the new NILE homepage for students

https://askus.northampton.ac.uk/Learntech/faq/230368

Find out about the exciting move to Blackboard Ultra

Changes to the Blackboard Assignment Tool

Changes to NILE programme courses

NILE updates for anonymous marking

Virtual classrooms: A reminder not to use the Microsoft Edge browser

More improvements for the virtual classroom in March 2020

Creating Accessible content

See 3 steps towards making accessible content

How to meet the accessibility regulations in NILE

Checking how accessible your content is within NILE

University of Northampton finishes 28th in a World Wide Competition to improve accessibility

Improving your knowledge of creating accessible online content. During this one-hour essentials course, you will learn easy and practical steps to ensure your online content – documents, attachments, files, videos, animations and web copy – is accessible to anyone who needs it.

- To view dates and register for this training, please visit HR Self Service > navigate to the Course Catalogue > search for Creating Accessible Online Content.

- If you need help using the Staff Development function in U4BW please see the short user guide.

Creating innovative content / academic updates

Don’t Panic! Surviving and thriving in the world of online teaching

Using Xerte to make interactive e-tivities for the new IPE curriculum

Record and edit video using tools available

Dr Charlotte Dann reflects on winning STaR Award Tech Savvy Lecturer of the Year

Alison Power is a fan of Xerte Bootstrap template

Training and Support

The Learning Technology Support site

Find out who your Learning Technologists is

What training opportunities are currently being offered (including creating video, Xerte, Turnitin, Padlet and NILE tools)?

See the full range of courses available through C@N-DO (including Storyboarding your module, CAIeRO for Individuals, and Exploring Feedback). For more support on these areas and moving towards semesterisation then email ld@northampton.ac.uk

Are you making full use of the excellent resources on LinkedIN for Learning? This is available for all staff and registered students.

Information on all courses offered through the staff development NILE site

NILE is integrated into the Active Blended Learning (ABL) process at The University of Northampton and we need to ensure that it is being used effectively by staff in order to provide a quality student experience.

Building on the guidance which was initially produced in January 2012, the framework has now been updated to cover the minimum standards which are expected on a NILE site. This was approved at University SEC in March, 2020 and is subsequently being used as the basis for the new NILE templates which have been developed for the 2020/21 academic year.

Guidance is also provided on how to set up NILE courses for the upcoming academic year?

New Box View to Bb Annotate

At the end of June, staff will notice a change in the way that they annotate students’ essays and reports in the Blackboard Assignment tool. Many staff use Turnitin to mark essays and reports, etc., and this update does not affect Turnitin at all; however, staff using the Blackboard Assignment tool will want to familiarise themselves with this update.

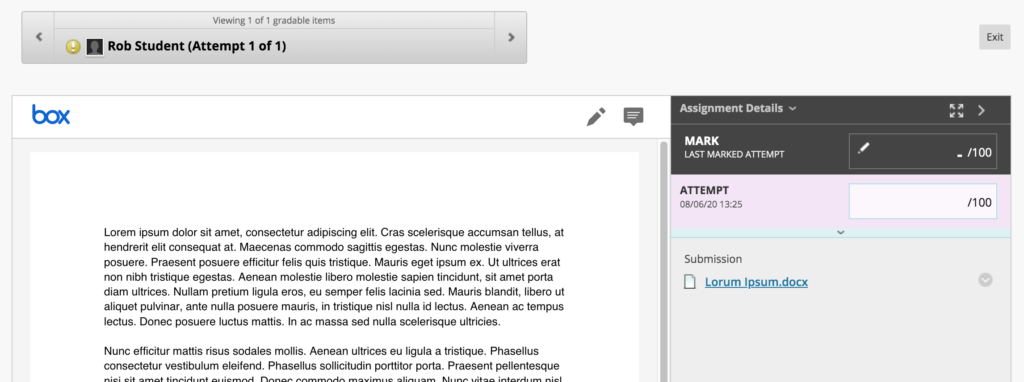

At present, the annotation function in the Blackboard Assignment tool is provided by New Box View, and it looks like this:

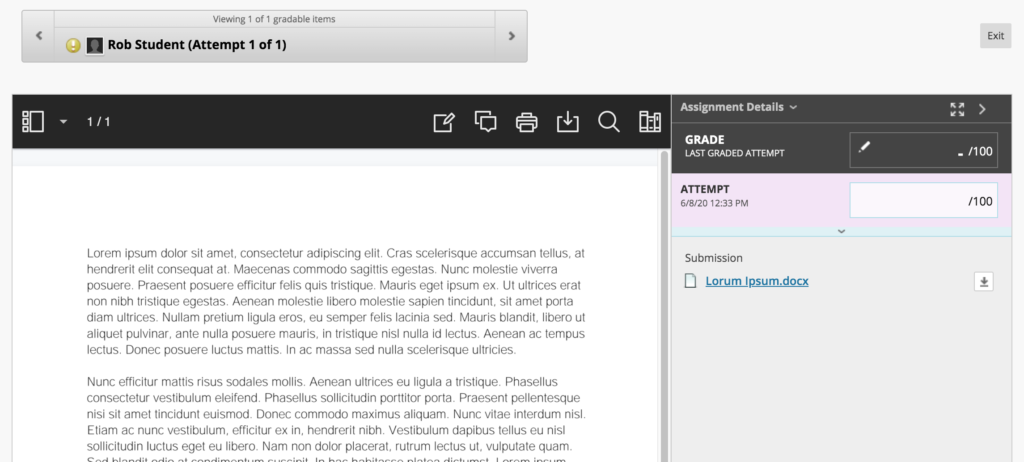

At the end of June, Blackboard are replacing New Box View with Bb Annotate. Following this upgrade you will notice that the tool looks a little different, and you’ll find that the annotation options have been greatly improved:

If you are planning on using the Blackboard Assignment tool to provide feedback and grades to students from July 2020 onwards, please familiarise yourself with the new Bb Annotate tool. Full guidance is available at: https://help.blackboard.com/Learn/Instructor/Assignments/Grade_Assignments/Bb_Annotate

Notes about the migration from New Box View to Bb Annotate

- All pre-existing annotations created through New Box View will be migrated and visible in Bb Annotate.

- When a student or a member of staff accesses an annotated file during the migration, it will take a little bit longer to load but will be displayed in the new Bb Annotate viewer.

- If a member of staff is actively annotating a file using New Box View during the migration, the file will not migrate to Bb Annotate until the member of staff has completed that session. Upon loading the submission file again, it will display in the Bb Annotate viewer.

- Members of staff will be able to delete annotations as well as add new comments to any existing comment created using New Box View.

Supported file types in Bb Annotate

You can view and annotate these document types directly in the browser with Bb Annotate:

- Microsoft Word (DOC, DOCX)

- Microsoft PowerPoint (PPT, PPTX)

- Microsoft Excel (XLS, XLSM, XLSX)

- OpenOffice Documents (ODS, ODT, ODP)

- Digital Images (JPEG, JPG, PNG, TIF, TIFF, TGA, BMP)

- Medical Images (DICOM, DICM, DCM)

- PSD

- RTF

- TXT

- WPD

Help and support with Bb Annotate

Full guidance on using Bb Annotate is available at: https://help.blackboard.com/Learn/Instructor/Assignments/Grade_Assignments/Bb_Annotate

Staff can also get help and support with Bb Annotate from their learning technologist:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-help/who-is-my-learning-technologist

What?

Through the suggestion of LearnTech Manager Rob Farmer and I were invited/sent along to our inaugural two-day Faculty of Health, Education & Society course development workshop to experience, and hopefully contribute to, the discussion and development of the new Interprofessional Education (IPE) module which was to run for level four students in the 19/20 academic curriculum. Social Work England (SWE) state Education and Training Providers should ‘ensure that students are given the opportunity to work with, and learn from, other professions in order to support multidisciplinary working’ (SWE, 2019:11).[1] It is therefore imperative that all Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) and SWE Health and Social Care programmes demonstrate commitment, delivery and implementation of IPE. However, perceptions of IPE as an additional learning burden for both academics and students alike are problematic and, as such, IPE has to be incorporated into existing curriculums so as not to create a significant amount of extra work for those teaching and studying on professional services’ courses. Therefore, the challenge facing the development team was ‘How can we create a module that can be’:

- Embedded into existing courses

- Self-led for most of the course

- Engaging for students while instructionally effective

To fulfil this brief, we roughly followed the University of Northampton’s CAIeRO[2] process, which is based on the Carpe Diem (Salmon, 2016)[3] design approach; it was decided that the course would be predominantly delivered via self-directed e-tivities. E-tivities combine an online active, participatory experience for individual learners, as well as those working in groups, and facilitates learners to engage with effective pedagogically informed technologies that enhance their digital fluency.[4] The e-tivities developed for the module would incorporate automated, embedded quizzes, to assess and consolidate IPE concepts learned through seminar discussion, and reading and media resources. When considering which educational technology we could deploy, Xerte’s functionality, which encompasses the interactive, self-directed elements of our remit, appeared the obvious choice. Two of three e-tivities would utilise Xerte technology, therefore the CAIeRO team were split into two groups (one led by Liane and one led by myself). Through a creative banging of heads together, the content and design elements for two e-tivity resources were sketched out; I was nominated to go away and, over a three-month period, create the Xerte e-tivity slides.

So what?

Although I had a working knowledge of Xerte, and had used it within my own teaching, the self-directed learning brief meant that I needed to develop slides which promoted this design. The project was interesting in that I had creative freedom to explore and exploit Xerte’s versatility and the range of interactive pages which make Xerte such an effective educational digital tool.

Thus, I was able to embed videos, create multiple choice quizzes, downloadable reflective exercises, and utilise the drag and drop functionality, while the choice of Xerte templates enhanced the presentational style of the finished article making it visually appealing, and professional. However, not all was roses in the Xerte park. The CAIeRO consensus determined that the students should not be able to continue to subsequent pages unless correct answers were given. The multiple choice quiz function did not allow for the checking of multiple answers, which if incorrect, would block the advance of the learner through the slides. Luckily, with the knowledge and expertise of Anne Misselbrook our resident LearnTech Xerte guru, and the wider Xerte community, we were able to source a script which we added to the offending interactive page to produce the desired result.

Technical conundrums aside, it was a challenge to source the relevant content for the e-tivities. Cross departmental input was required, and this took more time than expected, meaning the project overran its projected endpoint.

Now what?

At the time of writing, the level four module is still running, so students’ thoughts and any learning and teaching impact is yet to be evaluated; however, practical improvements for future e-tivity projects can be discerned. Planning and design has to be more focused with concrete content developed pre-e-tivity construction, rather than ad-hoc proposals, which the e-tivity developer has to keep drafting, and re-drafting. As Phemie Wright has identified (2014), “very little research or literature is available regarding practical [learning] design advice” (p.173). As a result of the IPE project, my advice is, don’t just storyboard, have the content ready to go so that developer concentration is focused on the interactivity, and presentation of the design, ensuring the effective production of impactful learning resources.

Salmon, G. (2016) Carpe Diem – A team based approach to learning design. [Online]. Available at: https://www.gillysalmon.com/carpe-diem.html Accessed 04/10/19.

Salmon, G. (2016) E-tivities. [Online]. Available at: https://www.gillysalmon.com/e-tivities.html Accessed 14/02/20.

Usher, J. (2014) De-Mystifying the CAIeRO. [Online]. Available at: https://blogs.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/2014/12/24/demystifying-the-caiero/ Accessed on 14/02/20.

Wright, P. (2014). “E-tivities from the Front Line”: A Community of Inquiry Case Study Analysis of Educators’ Blog Posts on the Topic of Designing and Delivering Online Learning. Education Sciences, 4(2), pp. 172-192. Available at: https://search.proquest.com/docview/1554606873?accountid=12834&rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo Accessed on 04/10/19.

To view an example of the Xerte slides created for IPE, click on the following link:

[1] Social Work England (2019) Qualifying Education and Training Standards 2020. London: SWE.

[2] https://blogs.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/2014/12/24/demystifying-the-caiero/

[3] Rough in that, we loosely applied the 7 CAIeRO stages, but time constraints meant that ideas were never really fleshed out.

[4] See https://www.gillysalmon.com/e-tivities.html for further information on e-tivities.

New look-and-feel for the NILE homepage

June 2020 sees a new look-and-feel for the NILE homepage. While the new homepage is indeed radically different, NILE courses are entirely unaffected. You can read more about the new NILE homepage here:

What is the new NILE homepage for staff

https://askus.northampton.ac.uk/Learntech/faq/230369

What is the new NILE homepage for students

https://askus.northampton.ac.uk/Learntech/faq/230368

New NILE courses for the 20/21 academic year

New NILE courses for the 20/21 academic year will be available for use from the 2nd of June onwards. As usual, the new courses follow the standard template as set out in the NILE Design Standards, so you can create your courses afresh, or you can copy materials from your 19/20 courses into your 20/21 courses. To copy materials across, please follow very carefully our instructions about how to do this:

Bulk copying content between courses in NILE

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-guides/blackboard-learn#s-lg-box-15196768

Full information about finding and setting up your new NILE courses can be found in our FAQ – How do I set up my new NILE course for the upcoming academic year?

https://askus.northampton.ac.uk/Learntech/faq/180655

There are no significant changes to the way that module courses have been created, however, there are major changes to the way that programme courses have been created.

Changes to NILE programme courses

Earlier this year the Student Experience Committee approved changes to the way that programme courses are created in NILE. For many years each programme has had a number of different programme course variations in NILE, which meant that for most programmes there were often eight different variations, and no single course that collected together all students on a programme. From this year onwards there is now a single programme course per programme per academic year, and this course has all students on it who are taking the programme (all years of study, full- and part-time, single and joint honours). This means that a single honours student will be enrolled on one programme course, and a joint honours will be enrolled on both of their programmes courses, plus the joint honours programme course. Foundation students will also have a single programme course for all foundation students.

NILE updates for anonymous marking

As anonymous marking becomes the new normal for the 20/21 academic year, changes in the integration between NILE and the Student Records System mean that you will no longer see students on your NILE courses who have transferred or withdrawn from your modules. The main effect of this is that you can now safely use Turnitin’s ‘Email non-submitters’ tool.

Additionally, and to assist with the process of anonymous marking, the Learning Technology Team have put together the following guides for staff and students:

Anonymous marking guide for staff:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/sage/turnitin_anonymous

Guidance for students submitting work anonymously

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/sage/turnitin-submission/anonymous

Help and support with NILE

As ever, for help and support with any of the NILE tools, or simply to find out more about what NILE is and how the Learning Technology Team can help you, please see our website:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/

And do feel free to contact your learning technologist for advice and guidance about anything related to educational technology in general, or NILE in particular:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-help/who-is-my-learning-technologist

Recent Posts

- Blackboard Upgrade – January 2026

- Spotlight on Excellence: Bringing AI Conversations into Management Learning

- Blackboard Upgrade – December 2025

- Preparing for your Physiotherapy Apprenticeship Programme (PREP-PAP) by Fiona Barrett and Anna Smith

- Blackboard Upgrade – November 2025

- Fix Your Content Day 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – October 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – September 2025

- The potential student benefits of staying engaged with learning and teaching material

- LearnTech Symposium 2025

Tags

ABL Practitioner Stories Academic Skills Accessibility Active Blended Learning (ABL) ADE AI Artificial Intelligence Assessment Design Assessment Tools Blackboard Blackboard Learn Blackboard Upgrade Blended Learning Blogs CAIeRO Collaborate Collaboration Distance Learning Feedback FHES Flipped Learning iNorthampton iPad Kaltura Learner Experience MALT Mobile Newsletter NILE NILE Ultra Outside the box Panopto Presentations Quality Reflection SHED Submitting and Grading Electronically (SaGE) Turnitin Ultra Ultra Upgrade Update Updates Video Waterside XerteArchives

Site Admin