Active learning approaches are great for getting new perspectives, sharing ideas, co-creating knowledge and trying out new skills. Many of the recommended techniques for active learning in the classroom focus on encouraging participation and discussion; after all, the seminar model is a familiar one, and verbal contribution is a good way to gauge understanding and to generate a ‘buzz’ in the classroom. Right?

Right, but… (there’s always a ‘but’). As we at UoN continue to explore active pedagogies, and with an eye on inclusion and our upcoming Learning and Teaching Conference, I want to share some conversations I’ve had in the past few weeks that turn a critical eye on classroom discussion models and unpack them from an inclusion perspective.

What is ‘participation’ for, and what does it look like?

The first of these was a conversation with Lee-Ann Sequeira, Academic Developer in the Teaching and Learning Centre at LSE. It was inspired by her session at the recent Radical Pedagogies conference, and also by her thought-provoking blog post examining common perceptions of silent students in the classroom. I won’t repeat the content of that post here (though I definitely recommend reading it), but I wanted to pull out some points from the discussion that followed, which might be of interest if you’re experimenting with active learning approaches.

In some subjects, oral debate is a disciplinary norm, if not an employability requirement: those studying Law, Politics, Philosophy and so on can expect to spend considerable time developing these skills. In these and many other subjects though, debate or discussion is also used to support the learning process, and sometimes as a way to check whether students have prepared for the class. So when asking your students to contribute, it can be helpful to think about what you want to achieve, and how your learning goals should inform the format of that contribution. For example, when one of your goals is to help students develop the skills to effectively present their ideas to an audience, you might need to ensure that every student has an opportunity to do this, but when your goal is to explore and develop an idea from a range of perspectives, is it still necessary that every single student speaks? Aligning the structure of the activity to your goals or learning outcomes can help students understand what’s expected and focus their effort accordingly.

Quality not quantity

As Sequeira’s blog post observes, the literature on active learning focuses a lot on “how to draw [students] out of their shells” (Sequeira 2017). In addition to this, a quick Google search on “active learning” will reveal a myriad of magazine-style opinion pieces on the subject, many of which seem to be in danger of advocating verbal contribution almost for its own sake, and effectively conflating speaking with learning. How then to ensure that when using these approaches, our active classroom doesn’t become hostage to those who talk most, or echo chambers of students that feel they need to be seen to be ‘participating’?

One way to prevent this is by clearly establishing, and then building towards, high standards for individual contributions. When planning your session, think about what you’d like the end result to look like, and what contributions might be needed to get there – always bearing in mind of course that you are just one perspective, so you may not be able to define the ‘finished product’ of co-creation in advance! What you can do though, is think about what a good contribution might look like. Can you provide examples, or talk through this with your students? Then as the discussion unfolds, you can encourage students to think about their own and each others’ comments – do they build on previous comments, do they bring in new evidence, do they advance the understanding in the room?

Thinking fast and slow

Of course, participation is not just verbal – and not just immediate! Active learning should not mean ‘no time to think’. When considering your learning goals, think about fast and slow modes of interaction – is promptness important or does the topic need deliberation and reflection? Silence can be a powerful tool in the classroom if we can resist the urge to fill the space, and giving students time to think before answering can often lead to more developed responses, as well as being more inclusive for those who are less confident, more reflective and/or working in their second or third languages.

Also, as Sequeira points out, participation can be multi-modal – could your students contribute in other formats? And not just to classroom discussions, but also to decision-making processes (choice of topic etc), and to feedback and evaluation opportunities? Thinking about ‘contribution’ more broadly might help to make these processes more inclusive too.

Supporting contribution: ‘productive discomfort’ and ‘brave spaces’

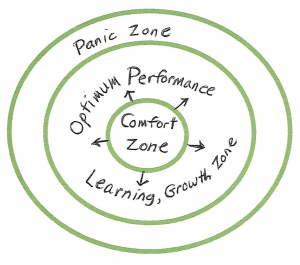

One of the goals of dialogic pedagogies is ‘productive discomfort’ – taking students out of their comfort zone and asking them to examine or defend their views – and being transparent about your pedagogy can also help students to understand this and recognize it in practice. This can be particularly important when working with students who are used to a more transmissive model of education, and are expecting you as the expert to tell them the answers. If your early discussions focus on sharing expectations and you know where your students are coming from, you’ll be able to plan, scaffold and facilitate more effectively.

One of the goals of dialogic pedagogies is ‘productive discomfort’ – taking students out of their comfort zone and asking them to examine or defend their views – and being transparent about your pedagogy can also help students to understand this and recognize it in practice. This can be particularly important when working with students who are used to a more transmissive model of education, and are expecting you as the expert to tell them the answers. If your early discussions focus on sharing expectations and you know where your students are coming from, you’ll be able to plan, scaffold and facilitate more effectively.

It can also help to acknowledge that collective exploration of ideas requires both intellectual and emotional labour, particularly as it can be intimidating to voice aloud ideas that are not fully formed. Much of the literature talks about creating ‘safe spaces’, but again this is an idea that merits a more critical inspection, particularly in the context of recent debates about free speech (‘safe’ for whom?). Another approach to this is the idea of ‘brave spaces’, replacing the comfort and lack of risk implicit in ‘safe’ spaces with an explicit acknowledgment of discomfort and challenge (Arao and Clemens 2013). Whichever approach you choose, creating trust will help to ensure students feel able to contribute, and there are a range of ways to do this, including discussion, modelling and constructive feedback. How you answer a ‘stupid’ question, whether or not you ‘cold call’ students, and how you respond to their input will all inform the norms of the learning space.

“The Socratic professor aims for “productive discomfort,” not panic and intimidation. The aim is not to strike fear in the hearts of students so that they come prepared to class; but to strike fear in the hearts of students that they either cannot articulate clearly the values that guide their lives, or that their values and beliefs do not withstand scrutiny.” (Speaking of Teaching, 2003)

Communication is a two way street

These ideas, and Sequeira’s observation about valuing active listening skills, led me on to the second conversation I want to share. Last week I attended a dissemination event for the ‘Learning Through Listening‘ project, led by Zoe Robinson and Christa Appleton at Keele. The project is looking at using global sustainability issues as an accessible context for developing conversations between individuals from different disciplines. This by itself is a laudable goal, as many of the ‘wicked problems’ of sustainable development will certainly need a interdisciplinary approach if we are ever to solve them. More broadly than that though, the project is also looking at developing active listening skills to support these conversations, and at listening as an area that is undervalued in education and in modern life. The event raised a few key questions for me, which I’ve noted below.

Active listening: the missing piece?

When we talk about communication skills with students, what do we prioritise? I work with many staff writing learning outcomes for our taught modules at Northampton, and much of the language we use for communication skills is proactive and performative: describe, explain, present, propose, justify, argue. Perhaps this is inevitable, as we need to make the learning visible in order to assess it, but there’s no doubt that these terms only give half of the picture of what communication actually is. By focusing so much on the telling, on the transmission of information and convincing of other people, are we giving students the impression that listening is less important? Are we encouraging the development of what Robinson described as the “combative mindset” so prevalent in 2018, and thereby inadvertently discouraging the development of curiosity, openness and willingness to learn from others – peers as well as tutors?

To rebalance the discourse around communication, the project at Keele used a number of activities to support the development of listening skills. One idea that really appealed to me was topping and tailing a series of guest speaker sessions – referred to as ‘Grand Challenges‘ – with a workshop before the lecture and a discussion session immediately afterwards. This allowed the students to think about what they already knew about the topic, and prepare to get the most of out of the session, and crucially also to follow up afterwards by sharing and developing some of the ideas it generated. Other interventions were slightly smaller scale, although perhaps easier to implement at a session or module level. Participants at the event last week got to try out some of these, and although I won’t cover them in detail here, the tasters below might give you some ideas for your classroom.

Learning to listen

One activity asked us to think about major influences that had shaped the way we as individuals see the world. We reflected individually on this, then shared what we felt comfortable with. I’ve never been asked to list these explicitly before, and it was interesting to actually see how everyone’s perspective is unique and created from a distinct combination of personal influences. We also talked about the factors that make it difficult for us to listen, covering everything from environment to agency to cognitive load. It was refreshing to realise that sometimes, everyone is bad at listening – and this was demonstrated when one of the session leads read aloud, probably only about a paragraph, and then pointed out that most of us would miss around half of any message we hear! I won’t spoil the final activity, in case you’re planning to go to one of the events, but also because the team at Keele will be releasing guidance on these as outputs from the project this summer. But needless to say it was fascinating – keep an eye on the website and the project blog for more.

Two more things struck me about the day overall. One was the emphasis on setup of the physical space. We spent part of the day seated in a circle, and part in rows facing a screen. This was a deliberate strategy by the project team and the contrast in terms of conversational dynamic was marked. This reinforced my view that we have the right approach with the classrooms at Waterside – it’s really remarkable what a difference movable furniture can make. The other thing I found interesting is that talking about listening made me (and the other participants too) suddenly very conscious of it. Even after the first activity, I found myself monitoring my communication with the other participants. Maybe it only needs one activity or discussion to highlight the issue, to begin to change how participants communicate?

Scaffolding discussion

The final point I want to make is something that was touched on in both of these conversations, and it’s about effective scaffolding. Both classroom and online discussion is usually more productive once the students have ‘warmed up’, got to know each other or developed a bit of confidence. There are lots of ways to approach this. In the event at Keele, for example, we started with a relatively uncontroversial topic – not many people in a university context will disagree that the UN sustainable development goals are a good thing, although they might disagree about how to address them. This can be a good way to introduce dialogic pedagogies, before working towards more heated or controversial topics (see this guidance from the University of Queensland on using controversy in the classroom). At Keele we also started with group discussion before we moved on to the one-to-one. This might be counter to the usual think-pair-share approach to scaffolding, but it did mean we had all spoken, and had some idea of where others in the room were coming from, before moving into more in-depth discussion. There’s also something to be said for reflecting on your question technique – are the questions you ask opening up or shutting down discussion?

These two conversations have given me lots to think about in terms of how we ‘do’ active learning. If you have any thoughts on this from your own experience, as always I’d love to hear them, so please add them as a comment. One last question to end with, thinking back to your last teaching session. Who in the room didn’t contribute, and why might that be?

References:

Arao, B and Clemens, K. (2013) “From Safe Spaces to Brave Spaces: A New Way to Frame Dialogue Around Diversity and Social Justice”. In Landreman, L.M. (ed.) The Art of Effective Facilitation: Reflections from Social Justice Educators. Sterling, Virginia: Stylus Publishing LLC, pp135-150.

Robinson, Z. and Appleton, C. (2018) Unmaking Single Perspectives (USP): A Listening Project [online]. Available from: https://www.keele.ac.uk/listeningproject/ [Accessed 27 March 2018]

Sequeira, L. (2018) Heresy of the week 2: silence in the classroom is not necessarily a problem. The Education Blog [online]. Available from: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/education/2017/01/19/heresy-of-the-week-2-silence-in-the-classroom-is-no-problem/ [Accessed 27 March 2018]

The move to Waterside is fast approaching, and there are a number of important deadlines this year for us as staff members getting ready for the move. With this in mind, here’s a quick timeline that tries to pull together what’s happening when in preparation for the move. It’s intended to help you see what help is available to you, to support you in meeting these deadlines, and also how you might be able to use some of this work towards another target many of you have for the year – gaining your HEA Fellowship.

The move to Waterside is fast approaching, and there are a number of important deadlines this year for us as staff members getting ready for the move. With this in mind, here’s a quick timeline that tries to pull together what’s happening when in preparation for the move. It’s intended to help you see what help is available to you, to support you in meeting these deadlines, and also how you might be able to use some of this work towards another target many of you have for the year – gaining your HEA Fellowship.

Download the map: Supporting key milestones towards Waterside [PDF]

Of course, different members of staff will have different targets and priorities, and not all of these are reflected here. Some Faculties and subject groups might also have their own internal deadlines for institutional projects like the UMF Review, so always check if you’re not sure. We’ve tried to capture the ones that are generally relevant to most academic staff, but if we’ve missed any, please let us know!

Over the past couple of years, lots of different people have asked me about our curriculum change project here at UoN. From teaching staff and students here at the University, to Northampton locals and parents, and even learning and teaching experts at other universities, there is increasing curiosity around the idea of a university without lectures. The lecture theatre has long been an iconic symbol of higher education, heavily featured in popular culture as well as many university recruitment campaigns. So how to explain why we think that we can do better?

Here are some of the reasons why I think that active blended learning (or “you know, just teaching” as I often hear it described), is the way of the future* for student success. What are yours?

- It’s effective for learning. Pedagogic research tells us that it is important for students to be actively involved in their learning – that is, to have opportunities to find, contextualise and test information, and link it to (or explore how it differs from) their prior understanding. Students who construct their own knowledge develop a deeper understanding than students who are just given lots of information, memorise it for the assessment and then promptly forget it. Who was it that said “Tell me and I forget, teach me and I may remember, involve me and I learn”? There is debate about the source of the quote, but there’s a reason it has endured…

- It can be more inclusive. Writers and educators like Annie Murphy Paul and Cathy Davidson are among many who question whether lecturing as a teaching approach benefits some students more than others – or indeed whether the students who succeed most in lecture-intensive programmes are doing so in spite of (rather than because of) the teaching approach. Now, active blended learning is not an easy fix for this challenge, and if not carefully designed it can also create environments that can disadvantage some learners (noisy classrooms can be difficult for students with language or specific learning difficulties, for example, and online environments can be challenging in terms of digital literacy). But with forethought and planning, ABL can help to ensure that all students have a voice and a role in the learning environment, and evidence suggests that it can reduce the attainment gap for less prepared students.

-

It’s more engaging / interesting / fun! When Eric Mazur used Picard et al.‘s electrodermal study to point out that student brainwaves (which were active during labs and homework) ‘flatlined’ in lectures, he may have been at the extreme end of the argument. But from the student perspective, anyone who has been a student in a long lecture (or who has observed rows of students absorbed in their laptops or phones) knows how easy it is to switch off in a large lecture environment. And from the tutor perspective, anyone who has been tasked with giving the same lecture multiple times knows that interaction and contribution from the students is vital to breaking it up. Smaller, more discursive classrooms allow for variety; for more and different voices and ideas to be shared.

- It scaffolds independence. Our students are only with us for a short time. If we teach them to depend on an expert to tell them the answers, what will they do when they don’t have access to those experts any more? The Framework for Higher Education Qualifications says that graduates should, among other things, be able to “solve problems”, to “manage their own learning”, and to make decisions “in complex and unpredictable contexts”. Our graduate attributes say that our students should be able to communicate, collaborate, network and lead. We don’t learn to do these things just by listening to someone else tell us how.

- It recognises how learning works in the real world. Think about the last time you really tried to learn something new. How did you go about it? You may have been lucky enough to have access to experts in that area, but chances are – even if that’s true – you also looked it up, asked some people, maybe tried a few things out. Probably you synthesised or ‘blended’ information from more than one source before you felt like you’d really ‘got it’. To be a lifelong learner, we need to be able to find and assess information in lots of different ways. This is exactly what our ABL approach is trying to teach.

Our classrooms at Waterside may look different to the iconic imagery commonly used to depict the university experience. But maybe it’s about time…

*Looking back on the development of university teaching, there is some debate around how we got to where we are: around what is ‘traditional‘ and what is ‘innovative’ in teaching; and also on whether the ubiquity of the lecture is a result of the economics of massification rather than the translation of pedagogic research into practice. Although it is always good to keep an eye on how practice has developed, I see no need to replicate these debates here – instead, this post is deliberately intended to be future focused, on how best to move forward from this point.

As a result of the University’s Active Blended Learning strategy, some teaching staff are considering using some contact time to support learners in the online environment as well as in the classroom. There are many reasons why you might choose to do this: perhaps you want to increase the flexibility for your cohort so they don’t have to travel; perhaps you need to help your students develop their digital literacy; perhaps running a teaching session online allows you to do something you couldn’t do in the classroom (like including a guest speaker, or allowing students time to draft and revise before sharing their thoughts). Or perhaps you just want to add some more structure, guidance and feedback to regular independent study activities.

Whatever your motivation, there are some tips that can help you think about how to use that contact time well, and make online learning a rewarding experience for you and your students.

Transparent pedagogy and clear expectations

Recent research with our students highlighted that they don’t always feel prepared for independent study, and often come to university expecting to ‘be taught’ rather than to have to work things out for themselves (the full report can be downloaded here). Scaffolding the development of independent learning skills is a gradual process, with implications for online as well as classroom teaching – particularly as this way of learning may be new to your students too (at least in formal education contexts). So how do you avoid students feeling like they’ve been ‘palmed off’ with online activities, when national level research tells us that many applicants expect to get more class time than they had at school?

It’s worth setting time aside early on to have frank conversations about how learning works at university level, and about how the module will work, but also about why those choices have been made. Students can sometimes be unaware of the level of planning and design work that goes into a module, so it helps to explain why you’re asking them to do the tasks you’ve planned – in the discussion forum, for example, why is it important for them to engage with opinions or ideas shared by other students? You don’t need to be an expert on social constructivism to explain that learning to research, communicate and collaborate online are crucial skills for graduates. And if it’s the first time you’ve tried something, don’t be afraid to say so, and acknowledge that you’re learning together! Keeping the conversation open for feedback on teaching approaches will help improve them in the future.

It’s worth setting time aside early on to have frank conversations about how learning works at university level, and about how the module will work, but also about why those choices have been made. Students can sometimes be unaware of the level of planning and design work that goes into a module, so it helps to explain why you’re asking them to do the tasks you’ve planned – in the discussion forum, for example, why is it important for them to engage with opinions or ideas shared by other students? You don’t need to be an expert on social constructivism to explain that learning to research, communicate and collaborate online are crucial skills for graduates. And if it’s the first time you’ve tried something, don’t be afraid to say so, and acknowledge that you’re learning together! Keeping the conversation open for feedback on teaching approaches will help improve them in the future.

In conversations about pedagogy, be sure to make space for your students to talk about their expectations and previous experiences. This might help them identify aspirations and areas for development, but it will also inform your planning, and a shared understanding of responsibilities will make the learning process run much more smoothly. Consider co-creating a ‘learning contract’, exploring issues like how often you expect them to check in on social learning activities on NILE, and how (and how quickly) they can expect to get responses to questions they pose there.

Building relationships

A key element of success in any learning environment is trust. This doesn’t just mean students trusting in you as the subject expert, and trusting that the work you’re asking them to do is purposeful and worthwhile (see above). It also means trusting that your classroom (whether physical or online) is a safe space to ask questions, and that feedback from peers as well as from you will be constructive and respectful. Some of this can be explicitly addressed with a shared ‘learning contract’, as above, but it also helps to reinforce this through the learning activities themselves. In the online environment, introducing low-risk ‘socialisation’ activities early on can help to build confidence and a sense of community, which will be invaluable in the co-construction of knowledge later on (see Salmon’s five stage model for more on this). Simple things like adding the first post to kick off a conversation, and explicitly acknowledging anxieties about digital skills, can make all the difference.

Trust also means students trusting that their contributions in the learning space will be acknowledged and valued. Many online tools, such as blogs and discussion forums, are specifically designed with student contribution as the focus, but with live tools, like Collaborate, you may need to plan activities specifically to support this, so that it’s not just you talking. After all, you wouldn’t expect a discussion forum to be composed of one long post from you, so with live sessions, the same principles apply! (see Matt Bower’s Blended Synchronous Learning Handbook for ideas).

Trust also means students trusting that their contributions in the learning space will be acknowledged and valued. Many online tools, such as blogs and discussion forums, are specifically designed with student contribution as the focus, but with live tools, like Collaborate, you may need to plan activities specifically to support this, so that it’s not just you talking. After all, you wouldn’t expect a discussion forum to be composed of one long post from you, so with live sessions, the same principles apply! (see Matt Bower’s Blended Synchronous Learning Handbook for ideas).

On the flip side of this, you also wouldn’t expect a student who was speaking in a live webinar to keep trying if they didn’t get a reply. So using the same principles, if you’re planning asynchronous (not live) learning activities, make sure you schedule teaching time to review your students’ views and ideas, whether online or in the next face to face session. Online, techniques like weaving (drawing connections, asking questions and extending points) and summarising (acknowledging, emphasising and refocusing) are invaluable, both for supporting conversation and for emphasising that you are present in the online space (see Salmon 2011 for more on these skills).

And if some of your students haven’t contributed, don’t panic! There could be lots of reasons for this. It may be a bad week for them, or a topic they don’t feel confident in, in which case chances are they will still learn a lot from reading the discussion. It may be that someone else already made their point – after all, if you were having a discussion in the classroom, you wouldn’t expect every student to raise a hand and tell you the same thing (if you need to check the understanding of every single student, maybe you need a test or a poll instead of a discussion). If participation is very low though, it may be that you need to reframe the question (as a starter on this, this guide from the University of Oregon, although a little outdated in technical instructions, includes some useful points about discussion questions for convergent, divergent and evaluative thinking).

Clarity, guidance, instructions, modelling

Last but by no means least, with online learning it helps to remember that students need to learn the method as well as the matter. A well-organised NILE site, clear instructions and links to further help will go a long way, but nothing beats modelling. Setting aside time in your face to face sessions to walk through online activities and address questions will save you lots of time in the long run.

We’ve written a few posts about learning styles in the past, and an important letter in yesterday’s Guardian added yet more support to the anti-learning styles side of the argument. Thirty academics signed a letter to the Guardian calling for teachers to end the use of learning styles and to make more use of evidence-based practices instead. Regarding the use of learning styles, the letter said that they were “ineffective, a waste of resources and potentially even damaging as … [they] can lead to a fixed approach that could impair pupils’ potential to apply or adapt themselves to different ways of learning.”1

You can read the entire letter here: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2017/mar/13/teachers-neuromyth-learning-styles-scientists-neuroscience-education

References

1. Sally Weale (2017) Teachers must ditch ‘neuromyth’ of learning styles, say scientists

“Now is the time of the essay film.” So said the film-maker Mark Cousins to the Guardian’s Charlotte Higgins in 2013. This realisation came to Cousins during the making his film, The First Movie, which was filmed in the Kurdish region of Iraq in 2009. One major problem that Cousins faced when making the film was that because the region was so dangerous, there were no cinematographers who were willing to work on the film. This did not stop Cousins though, and he decided to make the film himself using tiny, handheld cameras. What may have been perceived as an insurmountable obstacle was not only overcome, but actually created new ways of working and a new sense of freedom for Cousins. As he says,

“Now is the time of the essay film.” So said the film-maker Mark Cousins to the Guardian’s Charlotte Higgins in 2013. This realisation came to Cousins during the making his film, The First Movie, which was filmed in the Kurdish region of Iraq in 2009. One major problem that Cousins faced when making the film was that because the region was so dangerous, there were no cinematographers who were willing to work on the film. This did not stop Cousins though, and he decided to make the film himself using tiny, handheld cameras. What may have been perceived as an insurmountable obstacle was not only overcome, but actually created new ways of working and a new sense of freedom for Cousins. As he says,

“‘What I used to hate about filming is that I’d want to get up before dawn in Calcutta and film the sunrise. But you’d have to go knocking on the door of the director of photography, who’s sleeping, and say, ‘Please can you get up?’ This tiny camera, no bigger than a mobile phone, has become like a pen, he says: he can work alone, with the freedom of a prose essayist. ‘Now is the time of the essay film: that way of taking an idea for a walk.’”

Of course, the idea of the essay film, or cine essay as some film-makers like to call it, is not new, it’s just that it’s taken some time for technology to get to the point where the video camera and editing equipment are truly as portable and lightweight as the pen and the notebook. The idea of the film camera as a pen (or camera stylo as it is sometimes known) was introduced by Alexandre Astruc in his 1948 essay The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La Camera-Stylo.

Astruc was one of many film theorists who had high expectations about the potential of cinema to go beyond mere entertainment and spectacle, and who believed that cinema was capable of expressing complex, philosophical thought. He believed that cinema could be the intellectual equal of the novel or the philosophical essay, and nearly seventy years ago he said,

“Maurice Nadeau wrote in an article in the newspaper Combat: ‘If Descartes lived today, he would write novels.’ With all due respect to Nadeau, a Descartes of today would already have shut himself up in his bedroom with a 16mm camera and some film, and would be writing his philosophy on film: for his Discours de la Methods would today be of such a kind that only the cinema could express it satisfactorily. […] From today onwards, it will be possible for the cinema to produce works which are equivalent, in their profundity and meaning, to the novels of Faulkner and Malraux, to the essays of Sartre and Camus.”

But was Astruc right? Well, the philosopher John Gray might agree that he was. Indeed, Gray might well go further and say that the film-makers of today are doing a better job than academic philosophers in exploring some of the key philosophical issues of our time. In his review of a collection of Nietzsche’s lectures on education, entitled Anti-Education: On the Future of Our Educational Institutions, Gray tells us that,

“Justin Kurzel’s film of Macbeth presents an uncompromisingly truthful vision of the human situation unlike anything in the academic study of the humanities at the present time. The Wire and Breaking Bad explored the contradictions of ethics with a rigour and realism that is lacking in the baroque disquisitions on justice and altruism that occupy philosophers. Amazon’s version of Philip K Dick’s The Man in the High Castle is a more compelling rendition of the slipperiness of consensus reality than you will find in any number of turgid volumes of critical theory.”

Of course, neither Gray nor anyone else is saying that one form of expression is, per se, better than another. And Astruc’s point about Descartes is deliberately designed to be provocative and polemical. To argue that the cine essay is better than the essay is as pointless as trying to argue which account of the Holocaust is the best; Claude Lanzmann’s film Shoah, Primo Levi’s memoir If This Is A Man, or David Cesarani’s book The Final Solution. The point is that the essay and the cine essay can present different perspectives on the same subject, and will reveal different things about that subject through the specificity of the different media.

But the question we need to ask is what does this have to do with teaching and learning? Well, if we are persuaded that film is capable of expressing complex, philosophical thought, and if we are also persuaded that the equipment with which to make films is small, portable and already in the hands of many students, then it may follow that, on occasion, we might want to ask their students to submit a cine essay instead of an essay. And this is where the work of LSE lecturer Professor William A. Callahan comes in. Professor Callahan leads a course in Visual International Relations at LSE, and his students are regularly assessed via documentary films. The reason for this is, he says, that

“Documentaries encourage students to work collaboratively, reinforce concepts learnt, and generate new knowledge as well as resources that can be used by future students. Allowing students to create knowledge (and materials) together seems an excellent practice, so it’s a surprise it isn’t more widespread.”

Professor Callahan’s decision to introduce documentary making as an assessed component of his course came from his own experiences of making films, after he took a short course in documentary film-making and started making his own films. As he found out from his own experiences as a filmmaker, the camera is capable of recording the

“nonlinguistic and nonrepresentational aspects of knowledge: the laughs, sighs, shrugs, cringes and tears that are provoked in the on-camera interview process, which then can be edited into an engaging set of images that, in turn, can produce laughs, cringes and tears in the film’s audience.”

And it is this ability to convey meaning and to persuade through the use of images that he wants his students to understand when they take his course.

“That’s what the students get by the end of the course. They know how to write an essay but by the end of the course they should know how to, not just convince us with their academic, rational thinking, but move us through their images, move us emotionally.”

While it may not be possible to get access to the kind of equipment used by Callahan and his students, mobile phone manufacturers are continually trying to persuade us of the high quality of the cameras in their phones. Apple’s Shot on an iPhone campaign was a major part of the iPhone 6 release, Samsung have their own Captured on a Samsung S7 gallery, and most of the other big mobile manufacturers make great claims about the quality of the cameras in their phones. And there are now film festivals entirely dedicated to screening films shot on mobile phones, including the Mobile Motion Film Festival and the Mobile Film Festival, which is running for the twelfth time in 2017. Given than many of these devices are already in the pockets of our students, is now a good time to consider the cine essay?

Tips and recommendations

1. Probably the most important recommendation for anyone thinking about asking their students to submit a film or documentary, is firstly to have a go a making a film yourself. If you don’t have your own film-making gear, the LearnTech team can lend you an iPad so that you can have a go at making a film. The LearnTech iPads come with iMovie (a film editing program), so you can film and edit on the iPad. You can also borrow an iPad tripod from the LearnTech team.

2. If you don’t know where to start there are some usful introductory guides about making films on mobile devices. This one from Tom Barrance is worth a look: http://learnaboutfilm.com/making-a-film/filmmaking-iphones-ipads/

3. You can learn how to use iMovie to edit your film by signing up to the course on Lynda.com. All staff at the University can access Lynda courses for free (unfortunately students cannot access Lynda courses for free at the present time). The iMovie on iPad course is here: https://www.lynda.com/iMovie-tutorials/iMovie-iOS-Essential-Training/165441-2.html

4. If you can get a few people together then it may be possible to run a one day workshop for staff who are interested in learning how to film and edit using iPads. If this is something you’d like to do, feel free to email me: robert.farmer@northampton.ac.uk

5. This one is important. While the LearnTech team can lend iPads to members of staff for short periods of time, there is nowhere in the University where students can borrow film-making equipment (unless they are film/media/photography students). Thus, any film or documentary assignment will rely on students having their own equipment. Although most students do have smartphones, not all will have one, so you may want to make any film assessment into group projects.

6. If you do decide to alter an assessment to make it a film submission you will need to have your module re-validated. This is not an especially onerous process, but you may like to ask a Learning Designer to help you with this. Learning Designers can help you to design a suitable moving image assessment and can check through your learning outcomes to ensure that new assessment aligns with the learning outcomes. To change a module for the forthcoming academic year, you will ideally need to be ready to submit the revalidation paperwork in the January of the current academic year.

7. Prior to making any changes to a module and introducing a film/documentary assignment, it may be worthwhile asking your current students what they think of the idea.

8. Film-making can be quite time-consuming, so it might be best to err on the side of caution and keep the film length short, especially if it is the first time your students have sumitted a film. Five minutes is plenty of time, and could easily equate to 2.5 assessment units in a group project with two or three students per group. Again, a Learning Designer can help you with this process.

9. NILE fully supports student moving image submissions. Students can upload their completed films to http://video.northampton.ac.uk and can submit them to assignment submission points in NILE. Staff can view these film submissions directly in NILE without having to download them. Staff can also use http://video.northampton.ac.uk to upload their own films and embed them into NILE modules.

10. If you find that you really start to enjoy film-making and want to take things to the next level, you can learn all about making films from one of the great modern masters, Werner Herzog: https://www.masterclass.com/classes/werner-herzog-teaches-filmmaking

More information about William Callahan

If you would like to know more about William Callahan’s approach you can read about it here: http://lti.lse.ac.uk/lse-innovators/william-a-callahan-visual-international-politics-student-movies/

You can also watch him talking about it here: https://vimeo.com/140330542

You can view his films and the films of his students here: https://vimeo.com/billcallahan

And you can read his paper, The visual turn in IR: documentary filmmaking as a critical method here: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/64668/

Useful Links*

21 tips, tricks and shortcuts for making movies on your mobile: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/feb/12/21-tips-tricks-and-shortcuts-for-making-movies-on-your-mobile

10 tips for editing video: http://blog.ted.com/10-tips-for-editing-video/

7 interviewing tips for video storytellers: http://blog.ed.ted.com/2016/11/23/7-interviewing-tips-for-video-storytellers/

How our mobile-only TV package made the network news: http://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/academy/entries/c1b5506f-c627-417e-8958-ca36aaf86f01

Instead Of A Book Report, My Students ‘Wrote’ A Video: http://www.teachthought.com/the-future-of-learning/technology/instead-of-a-book-report-my-students-wrote-a-video/

6 Steps to Media Creation in the Classroom: http://dailygenius.com/6-steps-media-creation-classroom/

* Many thanks indeed to Belinda Green for the useful links.

The practice of teaching a class using PowerPoint is common at the University, with seating, video projectors and PCs in every teaching room all arranged to contribute to its adoption as the standard teaching method.

As a way of displaying information to a group, PowerPoint is effective, and whilst there are lots of other pieces of software (such as Prezi) that could lay claim to creating more vibrant and exciting presentations, few match PowerPoint’s effectiveness for its flexibility, ease of use, and the widespread digital literacy that comes with using such a popular Microsoft product.

It may sound like I’m rather fond of it, and yes I think it’s a good piece of software, especially as it’s fit for purpose, and almost certainly that there’s no better software for giving widespread presentations by a large group of staff.

So what’s the point of this blog post you may wonder?

Well, aside from the obvious technological differences, a lecturer standing at the front of a classroom talking over a set of PowerPoint slides is very much a reproduction of traditional teaching (otherwise known as didactic, direct instruction, or teacher centred learning).

That is, it’s a reproduction of how (most) lecturers taught 100-500 years ago when it was (and possibly still is) believed that students learned best by memorising the content that the lecturer taught and then reproduced that knowledge in an essay. Whilst it’s obvious that the educational landscape has changed radically, traditional teaching as a method has seen very little revision.

So before I jump into how active learning is different, let’s take a few moments to consider the benefits of traditional teaching with PowerPoint and the reasons it’s been so widely adopted.

- It is (comparatively) easy to create teaching materials

- It is easy to replicate lessons between groups

- Materials can be easily shared online and between tutors

- Many lecturers will have grown up with traditional teaching methods (and have been successful academically)

- Lecturers are often specialists in their fields rather than trained as teachers and therefore unaware of other teaching methods.

- There is often little communication between staff on teaching methods

- Staff have tended to stay in post for long periods (because we love the job)

- Classrooms with video projectors, smartboards and seating arrangements perpetuate the practice of teacher-centred learning

- Lecturers are busy and do not always have as much time as they would like to think about how they might develop their teaching

- PowerPoints are useful in consolidating your understanding of a subject

Clearly, it’s not all a bed of roses. We all know that creating quality PowerPoint presentations can take time, skill and a great deal of thought to get right.

In order to keep PowerPoint presentations up to date we have to:

- Learn new software / keeping up to date

- Research the subject, write and design slides

- Learn how to upload for students via Blackboard

- Load to PCs in class

- Constantly revise content

With such an investment in time and effort and understanding the problems of teaching at this level, perhaps it’s little surprise that many lecturers are wedded to their traditional teaching materials (who wants to lose their babies?)

But what if I could offer you a better deal … less work with better student results? More motivated and engaged students, a more vibrant and exciting learning environment?

Yes that’s exactly what’s on the table,

An alternative to traditional teaching is active learning (also known as student centred learning) This is learning centred around activities rather than a lecturer presenting content and students listening.

An activity could be any number of things: a presentation; a debate; a picture; video; poster; notes on a discussion board. And students could work in groups or individually.

The main emphasis here is that the student learns by participating in an activity: they may research, discuss, and consolidate their understanding into an output. One key difference in this teaching method is that lecturers act more like a facilitator than a ‘sage on a stage’.

I think it’s important to note at this point that PowerPoint itself is neither a traditional or active teaching tool, it is the means of how we (mostly) deliver traditional teaching, however it is also often adopted by students for active learning.

What does that mean and how will it look?

Well let’s replace that hour long PowerPoint presentation (that takes three hours to produce) with something like the following:

1. a few introduction slides that introduce the topic

2. an activity for the students to engage in, (perhaps some online research, and a discussion)

3. verbal feedback

4. a few slides at the end to wrap-up the activity

5. an ongoing task, for students to consolidate their learning on their personal blogs

It needs fleshing out a bit but I hope you’re getting the idea. It’s placing the focus on the participant rather than on you and allowing the students to do all the hard work.

The funny thing is that active learning is precisely the process that you go through when preparing a new PowerPoint (the process of research, writing, and reflection are all in there). We know it works as we do it all the time ourselves. The irony is that as lecturers we are getting a better learning experience than the students are.

You may be wondering what to do with all the PowerPoint files you’ve already made, and the answer is to keep them as your reference material. Not only can you dip in and out of them from time to time, stripping out slides as needs be, and share parts of them with students both in class and online, but they’re also a consolidation and document of your own ‘active learning’ journey, you can be confident that your time hasn’t been wasted.

Before I sign off, here are a few FAQs

How do you know my teaching methods aren’t effective?

I don’t, only you, the students, maybe an observer in your room, and feedback can tell you (honestly) if your teaching is effective. But generally speaking lecturers using ‘traditional teaching’ methods complain of ‘looking out on blank faces’, ‘students that are unengaged’, and a lack of understanding within assessments. This is an widespread observation and certainly not a criticism of your ability to teach.

Some of my students do very well at ‘traditional teaching’ why should we cater for unmotivated students?

It would be wrong to say that traditional teaching is not effective, for motivated students (especially those with a good memory) it can be very effective. But research shows that active learning provides better results for all students, especially those who are not traditionally academic. Rather than cater for the minority of motivated students, active learning offers a solution that’s more inclusive.

Is this new method of teaching tried and tested?

Yes, many teachers already adopt this style of teaching, especially those who have taught in language schools and HE, it just happens that it is yet to be widely adopted as the preferred method of teaching at this level.

Why should I learn a new way to teach?

It’s almost certain that your teaching is constantly evolving, every new piece of content, module you teach and method of delivery involves new skills learned, whilst changing to active learning may seem a giant leap in teaching style, the reality is that the process will involve lots of small steps, much in the same way as any other changes you have made. As educators we don’t stop learning, it’s just that by ‘doing it’ we don’t often notice.

What happens if I don’t have the time to do this?

We all know that time is precious, especially mid term when you are in the thick of teaching. However Rome wasn’t built in a day, and if you’ve read it this far then I’d strongly advise you to reach out for a helping hand from the Institute of Teaching and Learning (ILT) and from our friendly team of Learning Designers. ILT are very keen to promote improved learning techniques through their PGCAP programme and their C@N-DO workshops and they have the pedagogic knowledge to set you off on the right course. Another good source of help is to arrange a face to face, 1:1 session with one of the Learning Designers and see what happens – you will almost certainly find they’re full of good ideas and are there to help (email: LD@northampton.ac.uk).

If I already to this do I need to do anything?

There’s a good chance I’m preaching to the converted, but it’s still worth discussing this with a Learning Designer to promote good practice. If you’re doing this already then great, they’ll help you identify best practice and may want to use your teaching methods as a case study so you can help others discover the benefits of active learning.

Hopefully I’ve whet your appetite and you want to know more.

I hope you’ve found this blog post interesting, if so you may like to read the following posts:

Designing e-tivities – some lessons learnt by trial and error.

http://blogs.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/2016/08/18/designing-e-tivities-some-lessons-learnt-by-trial-and-error/

CAIeRO & Waterside.

http://blogs.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/2016/10/06/caiero-and-waterside-readiness/

What is the flipped classroom?

http://blogs.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/2015/01/16/what-is-the-flipped-classroom/

Will flipping my class improve student learning?

http://blogs.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/2015/08/27/will-flipping-my-class-improve-student-learning/

In the next post I’ll be reviewing a number of digital learning tools you can use in the classroom for active learning, the pros and cons of each and looking at a few examples of how lecturers are currently using these in the classroom.

Richard Byles

Learning Technologist.

I recently read an insightful piece from Charles D. Morrison, which argues, among other things, for a clear distinction between ‘information’ and knowledge’ in educational discourse. Morrison, like many others, holds that while information may be transferred (e.g. through telling or lecturing), knowledge cannot – that is, information must be contextualised, applied, experienced in order to become knowledge. This will be a familiar point to anyone interested in effective pedagogy, but the article is worth a read, not least because it communicates clearly the responsibilities of this for the student as well as the tutor. It’s also a point that bears repeating at this time of year, as we consider the new cohorts of students who have already begun to walk in to our classrooms.

Everyone, students and tutors alike, will bring something slightly different to the classroom. There will be differences in the prior knowledge and skills students have developed, but there may also be differences in the ways these are integrated into their experience – the preconceptions (and misconceptions) they have created in order to make new information make sense to them. This collection of intellectual baggage is what Phil Race refers to as ‘learning incomes’ – and it can really make a difference to how each student engages with new learning, even in the most carefully designed and structured learning activities. How then to ensure that each of these individuals can progress towards common intended outcomes?

Everyone, students and tutors alike, will bring something slightly different to the classroom. There will be differences in the prior knowledge and skills students have developed, but there may also be differences in the ways these are integrated into their experience – the preconceptions (and misconceptions) they have created in order to make new information make sense to them. This collection of intellectual baggage is what Phil Race refers to as ‘learning incomes’ – and it can really make a difference to how each student engages with new learning, even in the most carefully designed and structured learning activities. How then to ensure that each of these individuals can progress towards common intended outcomes?

Race argues that the best way to do this is to ask them what they already know, using one of our favourite tools here in Learning Design, the humble post-it. In the piece linked above, he describes a simple exercise designed to collate students’ thoughts on the most important thing they already know about a topic, and the biggest question they have. This kind of exercise is useful for helping teaching staff to identify knowledge gaps and misconceptions, but Race also points out another important gain: that “Learners are very relaxed about doing this, as ‘not knowing’ is being legitimised”. This can be particularly important for new students, who may lack confidence in their abilities, because it frames the classroom as a safe space for exploration, experimentation and failure (often a necessary precursor to success!).

If you’re thinking about using a similar diagnostic activity with your new learners this term, you might also find this post from Janet G. Hudson useful, as it includes a few more suggestions on how to gather data on common misunderstandings in your subject. Or, if you’re already using this type of activity, why not share your thoughts below on what has worked well for you?

We came across this great resource recently, from the Teaching Excellence and Educational Innovation Center at Carnegie Mellon University. It’s designed to help academics solve teaching problems through a three-step process:

We came across this great resource recently, from the Teaching Excellence and Educational Innovation Center at Carnegie Mellon University. It’s designed to help academics solve teaching problems through a three-step process:

- Step 1: Identify a PROBLEM you encounter in your teaching.

- Step 2: Identify possible REASONS for the problem

- Step 3: Explore STRATEGIES to address the problem.

To access the site, click on the image, or use this hyperlink: https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/solveproblem/index.html

I want to change my programme structure…

I want to include a placement / work-based learning / a Changemaker challenge…

I want to use a particular assessment or technology…

I want to ensure an equivalent experience for students at other sites…

What do I need to do?

The Learning Design team have collated a document listing the most frequently asked questions from CAIeROs and consultations over the past two years, along with answers provided by the appropriate support teams. Hopefully the guidance here can help you identify the processes and teams that are in place to support you with a range of course design issues including quality assurance, assessment, distance learning and technology issues.

The list has been added to the Sharing Higher Education Design (S.H.E.D.) site on NILE. You can access the site at http://bit.ly/SHED-NILE, but you will need to be enrolled to view the document.

We’ll keep this document updated as new questions and answers come up. Want to submit a question that we haven’t covered? Just email it to the Learning Design team at LD@northampton.ac.uk.

Recent Posts

- Blackboard Upgrade – February 2026

- Blackboard Upgrade – January 2026

- Spotlight on Excellence: Bringing AI Conversations into Management Learning

- Blackboard Upgrade – December 2025

- Preparing for your Physiotherapy Apprenticeship Programme (PREP-PAP) by Fiona Barrett and Anna Smith

- Blackboard Upgrade – November 2025

- Fix Your Content Day 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – October 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – September 2025

- The potential student benefits of staying engaged with learning and teaching material

Tags

ABL Practitioner Stories Academic Skills Accessibility Active Blended Learning (ABL) ADE AI Artificial Intelligence Assessment Design Assessment Tools Blackboard Blackboard Learn Blackboard Upgrade Blended Learning Blogs CAIeRO Collaborate Collaboration Distance Learning Feedback FHES Flipped Learning iNorthampton iPad Kaltura Learner Experience MALT Mobile Newsletter NILE NILE Ultra Outside the box Panopto Presentations Quality Reflection SHED Submitting and Grading Electronically (SaGE) Turnitin Ultra Ultra Upgrade Update Updates Video Waterside XerteArchives

Site Admin