Following on from the blog post, ‘What is the flipped classroom?’, it seemed that it would be useful to put the ideas discussed there into practice, and to design and build a flipped module in NILE. As you would expect, there is no one way of putting together a flipped module that will work well for everybody – how you choose to design and run your flipped course will depend on a number of things, such as the level of study, size of class, what you enjoy doing in your face-to-face sessions, and what it is that you’re teaching. How you design your course will also depend on what kind of blend you want between the online and the face-to-face teaching elements. For example, if you want to take a two hour a week face-to-face course, and put 50% of the teaching online, this could be blended as a one hour online and one hour face-to-face session every week. However, it could also be done as a two hour online session in week one, followed by a two hour face-to-face session in week two, and so on. You could also rotate the online and face-to-face sessions on a three or four (or more) week basis, or even have all of term one online, and all of term two face-to-face (or vice versa).

The (fictional) course that has been designed and built in NILE has been created with the following in mind:

Title of module: CRIT101: Critical Thinking – A Practical Introduction

Level: 4

Credits: 10

Duration of course: 12 weeks

Contact hours per week: 2

Blend: 50%

Blend type: weekly blend (1 hour online, 1 hour face-to-face per week)

Additionally, the course has been built with the aim that the face-to-face sessions should be highly participatory and focussed as much as possible on dialogue with and between students. Again, this is not necessarily how everyone will want to run their face-to-face sessions – you may prefer to do just in time teaching1, peer instruction2, team-based learning3, problem-based learning4, small-group teaching5, or any number and mixture of other things that you can do in a face-to-face teaching space.

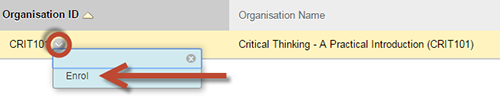

If you would like to find out more, you can enrol yourself on ‘Critical Thinking – A Practical Introduction’ and browse through the materials and the activities. The course begins with a set of three Panopto presentations which introduce the course and the NILE site to students, so this is a good place to begin when looking through the course. To access the course, login to NILE and click on the ‘Sites and Organisations’ tab. Type ‘CRIT101’ in the ‘Organisation Search’ box, and click ‘Go’. You will then see the course listed in the search results. Click on the drop-down menu next to CRIT101, and select enrol (see screenshot below).

The course is fully functional, so feel free to contribute to the discussion boards and take the tests, etc. It’s also very mobile friendly, so works well via the iNorthampton app on iOS and Android devices.

If you have any thoughts on the course, suggestions for improvements, etc., please feel free to respond to this blog post, or to email me directly at robert.farmer@northampton.ac.uk. If you would like to arrange a meeting with a learning designer to discuss what technologies are available in NILE and how you could further develop your own modules, please email LD@northampton.ac.uk.

Notes

1. Just in Time Teaching (JiTT) is a responsive method of teaching in which the content of the in-class sessions is determined by student responses to online activities, often only completed between 1 and 24 hours before the class begins. For more information see: http://www.edutopia.org/blog/just-in-time-teaching-gregor-novak

2. Peer instruction is a method of teaching developed by Eric Mazur at Harvard University in the 1990s. For more information, a good place to start is: http://blog.peerinstruction.net/2013/08/26/the-6-most-common-questions-about-using-peer-instruction-answered/

3. Team-Based Learning (TBL) is an approach to teaching and learning developed by Larry Michaelsen. For more information see: http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/team-based-learning/

4. For more information about Problem-based Learning (PBL) (and enquiry-based and action learning) see: http://www.learningandteaching.info/teaching/pbl.htm

5. A useful guide to small group teaching can be found in Phil Race’s book, ‘The Lecturer’s Toolkit, 4th Edition’ (Routledge, 2015). See, chapter 4 ‘Making small-group teaching work’.

Our colleagues at CfAP are often on the receiving end of poor assessment design. In this post, Kate Coulson, Head of CfAP, describes the impact on the student experience and looks at ways to ensure this won’t happen to your students…

“Maya* is an undergraduate in the second year of her degree. Throughout her first year, she was averaging a C grade in her assessments. Maya has just received her grade and feedback from her first assessment of her second year. She was given a D grade and the marking tutor advised her to visit CfAP to get some support and guidance in “understanding the question”.

When Maya meets with a CfAP Tutor she becomes very distressed and states that “the question didn’t make sense” and “I don’t know what I needed to include”. She also states that she spoke to her tutor directly as she was unclear about the assessment but their conversation left her more confused. When chatting to her course mates about the assessment, they had interpreted the requirements in a totally different way and she panicked and didn’t know what to do.”

When writing questions for essays or assignments it is imperative that you think about the student. Badly written essay questions confuse the student and can affect their confidence and performance in the task – sometimes even leading them to question whether University is the right place for them.

Tips to help you avoid the pitfalls:

- Allow time to plan your questions or tasks.

- Be clear about what knowledge and skills you want the students to demonstrate (these should be informed by your learning outcomes).

- When you are writing a question or task, consider the stage of the programme and module where it takes place, and evaluate whether the students have the content knowledge and the skills necessary to respond adequately.

- When scheduling, be aware of other assessments students will be given from other modules on the programme. Nobody benefits from students having to divide their time and energy between multiple deadlines.

- Discuss the assessment with your students – both the task itself and the purpose of it. Explaining why you have chosen this task, and how it will help them to reach the learning outcomes, will help them feel ownership. Be prepared to adjust in response to valid feedback.

- Share grading criteria and rubrics ahead of the assessment. Students should know what they are aiming for, and what satisfactory performance looks like. Better still, consider writing a model answer. This will help you to reflect on the clarity of the essay question, even if you choose not to share it with the students until after the deadline. It could also serve to inform the grading of students’ responses.

- Use your colleagues to critically review the question or task, the model answer and the intended learning outcomes for alignment.

- Use formative tasks to help students to develop their understanding of expectations and standards. Better still, plan out the ‘assessment journey’ when planning your module, to ensure students have opportunities to learn the process as well as the content of the assessment. The Assessment and Feedback cards from the JISC Viewpoints project can help you do this.

Writing good essay questions is a process that requires time and practice. Review your questions after the students have completed them, think about how the questions have been interpreted. Studying the student responses can help evaluate students’ understanding and the effectiveness of the question for next time.

Useful reading and resources:

The University’s Assessment and Feedback Portal provides more information about assessment design, including links to published research in this area.

The Assessment Brief Design project from Oxford Brookes gives detailed guidance on writing clear and targeted briefs.

For more on the great work done by the Centre for Achievement and Performance, visit the CfAP tab on NILE.

*”Maya” is a fictional character, although her story is based on real events.

One of the more discussed topics at the University of Northampton at present is the idea of the ‘flipped classroom’ or of students engaging in ‘flipped learning’. A major reason why this is being discussed now is that use of the flipped classroom could well be a major feature of the University’s new Waterside campus1, however this is not the only (nor even the best) reason for interest in this subject. As will undoubtedly be clear, the best reason for adopting a flipped learning approach to teaching and learning is that it offers pedagogical advantages, and we will certainly look at some of the evidence in favour of flipped learning in a later blog post. However, our purpose in this post is simply to outline what flipped learning is, and how one might go about doing it.

The key points in this post are:

1. Very simply put, the flipped classroom is one where students access content and engage in activities designed to develop their understanding before class, and then use the class time to discuss and engage in depth with issues, ideas and questions arising from the pre-class content and activities.

2. Whilst there may be some barriers to adopting this approach, most (if not all) can be overcome.

3. The flipped classroom is very relevant to the University of Northampton at the moment as it is one of the models of teaching and learning which will work very well in the new Waterside campus. However, there’s no need to wait until we get to Waterside to try it out, as it’s something that will work well right now.

4. There is a lot of support available to staff wanting to try out the flipped classroom, and staff are encouraged to try out this approach to teaching and learning.

What the flipped classroom is

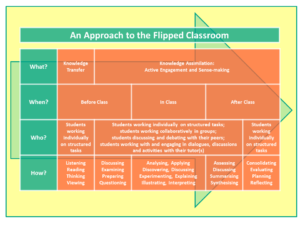

I was introduced to the idea of flipped learning in 2012 by the Harvard Professor Eric Mazur, when I attended his keynote speech2 at the annual conference of the Association for Learning Technology. The idea of the flipped classroom owes a great deal to the work of Mazur, whose ideas about peer instruction3 formulated at Harvard in the 1990s evolved into what we now term flipped learning. To use Mazur’s terminology, what happens in a traditional classroom is that class time is typically taken up with ‘knowledge transfer’, often a lecture, and students then complete tasks outside of class in order to process and understand the subject matter, which Mazur terms ‘knowledge assimilation’. What Mazur proposed is that the knowledge transfer stage should be covered prior to attending class, and that the class time could then be used to help students assimilate what they had read or watched prior to coming to class. The ‘flip’ is simply that knowledge transfer now happens outside class, and knowledge assimilation now happens in class.

“Mazur’s reinvention of the course drops the lecture model and deeply engages students in the learning/teaching endeavor. It starts from his view of education as a two-step process: information transfer, and then making sense of and assimilating that information. ‘In the standard approach, the emphasis in class is on the first, and the second is left to the student on his or her own, outside of the classroom,’ he says. ‘If you think about this rationally, you have to flip that, and put the first one outside the classroom, and the second inside. So I began to ask my students to read my lecture notes before class, and then tell me what questions they have [ordinarily, using the course’s website], and when we meet, we discuss those questions.'” 4

Putting the flipped classroom into practice

Obviously no classes at Northampton are taught only via lectures, and I suspect that very few (if any) lectures at Northampton are pure didactic monologues, but Mazur’s ideas could still be used to good effect to free up more class time to spend with students helping them to understand the material and the subject in more depth.

If this approach appeals to you, then an example of how you could put it into practice is by putting your lectures online, and using your class time to engage students in activities and tasks which will help them to fully understand the material which was covered in your lecture. The online lectures should be short, certainly no more than thirty minutes, but two fifteen minute lectures would be preferable. And supporting the video lectures will probably be some reading, a book chapter or journal article perhaps. Students may watch your lectures a few times in order to get the most from them, and students for whom English is not a first language may benefit greatly from the ability to watch and re-watch the lectures. You’ve now freed up an extra hour to spend with your students, so what’s the best way to use that hour?

Well, there are plenty of options here. If you’d prefer a more teacher-led session then one idea would be to ask your students to complete a pre-class test or survey in order to find out where the gaps in their understanding are. Perhaps you’d prefer to give them a test so that you can check their understanding yourself, or perhaps you’d prefer the students to determine for themselves what they did and did not understand, so you ask students to submit questions about the material. Their questions or their test results could then form the basis of a class session in which you discuss and answer the questions that the students submitted in the survey, or provide further clarification on the things they got wrong in the tests. This approach is often called ‘just in time teaching’ as you don’t really know what you need to cover in class until the test or survey results have been submitted, and this is often less than 24 hours before the class is due to start. If you’d prefer something more student-led then you could still use a pre-class test or survey, but this time you take the students questions (or develop your own questions based around the things they got wrong in the tests) and get the students to answer their questions themselves. This is the approach that Mazur uses, which he terms peer instruction.

“Mazur begins a class with a student-sourced question, then asks students to think the problem through and commit to an answer, which each records using a handheld device (smartphones work fine), and which a central computer statistically compiles, without displaying the overall tally. If between 30 and 70 percent of the class gets the correct answer (Mazur seeks controversy), he moves on to peer instruction. Students find a neighbor with a different answer and make a case for their own response. Each tries to convince the other. During the ensuing chaos, Mazur circulates through the room, eavesdropping on the conversations. He listens especially to incorrect reasoning, so ‘I can re-sensitize myself to the difficulties beginning learners face.’ After two or three minutes, the students vote again, and typically the percentage of correct answers dramatically improves. Then the cycle repeats.” 5

Other options could involve a blend of just in time teaching and peer instruction. These are not the only approaches though, and whilst there is no one correct way of doing things, it’s probably safe to say that an approach which sees the students actively engaged in class is likely to lead to them learning more than an approach in which the students are passive. A visual idea of how the flipped classroom could work in practice is given below:

Waterside – a flipped campus?

Can you flip a whole institution? Yes, you can. Clintondale High School in Michigan started flipping its classes in 2010, and now delivers all classes using the flipped model. They claim that this approach has led to dramatic reductions in both failure rates and discipline problems6. The University of Technology, Sydney, has developed a teaching and learning strategy which fits extremely well with flipped classrooms7, and has set up its own Flipped Learning Action Group to promote the use of this approach8. Does this mean that Waterside going to be a flipped campus? No, it doesn’t. Whilst we won’t have any lecture theatres, and while much of the teaching and learning will happen in smaller teaching spaces (twenty to forty students), a one-size-fits-all approach would not be the best option for the new campus. Nevertheless, what is encouraged for Waterside is what is encouraged at both Park and Avenue campuses here and now, which is participatory, student-led teaching and learning and the use of both class time and technology to engage students in active, exciting and transformative learning experiences.

Will students complain if I flip my classroom?

Possibly. Students may expect lectures and they may think that they learn from them. Students may also like lectures because they’re easy: not much is expected from attendees at lectures as they are “the teaching moment that most promotes passivity and discourages participation.”9 If you adopt a flipped learning approach then students will have to work harder both in class and before class. This is a good thing, and if you want to counter objections from students who want you to lecture you could refer them to bell hooks’ essay quoted above, ‘To Lecture or Not’10, where she tell us that “When we as a culture begin to be serious about teaching and learning, the large lecture will no longer occupy the prominent space that it has held for years.” You could also refer them to Graham Gibbs’ article, ‘Twenty terrible reasons for lecturing’11, in which he explains and provides evidence as to why lecturing does not “give students a rich and rewarding educational experience.”12 In addition, the recent National Union of Students’ publication ‘Radical Innovations in Teaching and Learning’ is worth referring students to as it asked universities to, amongst other things, consider what place the lecture has in “a modern, democratic university.”13

Support for flipping your classroom

What support is available to academics wanting to try out flipped learning? Well, an excellent place to start is with the Learning Designers and the Learning Technology Team. The Learning Designers will be able to explain more about flipped learning, and will be able to help you successfully plan and implement flipped classroom sessions. And the Learning Technology Team will be able to provide you with training and support regarding the technologies that you may want to use as part of your flipped classroom sessions.

To end, it’s worth pointing out that changing the way one teaches takes time, and without support from professional services staff, colleagues and managers, change is not likely to happen. Change, especially radical change, also needs failure to be acknowledged as a possible and legitimate outcome, as not every new technique that we try out will be a success. However, perhaps the flipped classroom offers a low-risk opportunity for change, as there is plenty of training and support available from the Learning Designers and the Learning Technology Team, and the evidence, which we will look at in a later posting, seems to suggest that this is an approach that works.

Contacts

Learning Designers: LD@northampton.ac.uk

Learning Technology Team: LearnTech@northampton.ac.uk

References

1. Parr, C. (2014) ‘Six trends in campus design: 5. Informal, flexible learning spaces.’ Times Higher Education Supplement. December 2014. [online]. Available from: http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/features/six-trends-in-campus-design/4/2017412.article

2. Mazur, E. (2012) ‘The scientific approach to teaching: research as a basis for course design.’ YouTube. [online]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aYiI2Hvg5LE

3. Lambert, C. (2012) ‘Twilight of the Lecture.’ Harvard Magazine. March/April 2012. [online]. Available from: http://harvardmagazine.com/2012/03/twilight-of-the-lecture

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. See: Clintondale High School (2012) Our Story. [online]. Available from: http://flippedhighschool.com/ourstory.php

7. UTS (2104) ‘Learning 2014 Strategy.’ YouTube. [online]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rL0eFmac7mA

8. UTS (2014) ‘Flipped Futures.’ UTS Newsroom. August 2014. [online]. Available from: http://newsroom.uts.edu.au/news/2014/08/flipped-futures

9. hooks, b. (2010) Teaching Critical Thinking: Practical Wisdom. Abingdon: Routledge. p.64.

10. Ibid. pp.63-68.

11. Gibbs, G. (1981) Twenty terrible reasons for lecturing. SCED Occasional Paper No. 8, Birmingham. 1981. [online]. Available from: http://shop.brookes.ac.uk/browse/extra_info.asp?compid=1&modid=1&deptid=47&catid=227&prodid=1174

12. Ibid.

13. NUS (2014) Radical Interventions in Teaching and Learning. [online]. Available from: http://www.nusconnect.org.uk/resources/open/highereducation/Radical-Interventions-in-Teaching-and-Learning/

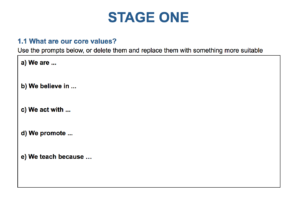

The first stage of a CAIeRO is all about outlining a vision for the programme or module – what is it for? what do you want it to do? – and then drafting this into something concrete to work on.

For new programmes, refining the vision or idea is usually the logical place to start; defining the goals and the parameters, in discussion with colleagues on the course team, and with support from learning designers.

For new programmes, refining the vision or idea is usually the logical place to start; defining the goals and the parameters, in discussion with colleagues on the course team, and with support from learning designers.

For existing programmes, this step may initially seem quite straightforward. A quick reference to the programme specification should tell us what we need to know. In practice though, programmes and modules get tweaked and adjusted over time, and for many programme teams it is rare to get the opportunity to spend time sharing ideas about the bigger picture of what should be taught, and how students might learn it. Stage 1 of the CAIeRO is your opportunity to revisit the aims of the programme and do a health check: asking is this still what we want to achieve? And if it is, then is this still clearly reflected in the modules that make up the programme?

As with all of the CAIeRO elements, you may spend more or less time on each task depending on the needs of your programme. That said though, it is always worth taking the time to ensure a shared vision before moving forward.

The mission statement

This first activity asks you to define, as a group and in a limited number of words, the ‘mission’ of the programme. This helps to ensure that everyone in the team is aiming for the same thing, so that we design a consistent experience for the learner. This step is particularly useful for programmes that combine modules from different areas of the discipline, and it allows those leading different modules to share their perspectives and experience. Reaching consensus can sometimes be tricky, but it does make everything that comes afterwards much easier! Once you have this, you can create statements for each of your modules, that align with and develop the mission for your programme.

The ‘look and feel’

The ‘look and feel’

This stage of the workshop uses Course Features cards, designed by the Open University Learning Design Initiative. You’ll be asked to narrow down the features to those which are most important to the ‘look and feel’ of your course. This may sound a little ‘woolly’, but it’s an easy umbrella term for the different elements that need to be considered (pedagogic approach, guidance and support, content, interaction and so on).

As with the mission statement, this activity helps the team to work towards a consensus on the type of learning experience you want to create. But there are also other gains to this process, that sometimes go unnoticed:

- It provides a common language to help you and your colleagues talk about how you like to teach – particularly for those teaching strategies that are based on tacit experience. Choosing these stimulates discussion about them: what do you mean by …? how does that work? why is that the best approach? This discussion is useful for skill sharing and personal development, as well as narrowing down the most effective approaches for the context.

- It brings the learners into the heart of the conversation, as choices need to be made about what learning approaches they might use, and what kinds of support they might need.

- It helps to ensure that you are considering all the elements that make up a balanced course.

Constructive alignment and backwards design

The next three sections or tasks ask you to focus in on the module level, though you will need to keep the programme-level outcomes and assessment map in the back of your mind to ensure alignment. We’ll look at the building blocks that form the basis of each module: the learning outcomes, assessment tasks and learning activities. We’ll be looking to flesh out the initial vision into a more structured pathway that is constructively aligned, asking: how do we define the learning in terms of demonstrable outcomes? how do we design assessment opportunities that allow the learner to demonstrate achievement of those outcomes? how do we create learning activities that support the learner to reach the intended outcomes and succeed in the assessment? For this we often use a ‘backwards design‘ approach, beginning with what we want the learner to know and be able to do at the end of the module, and working backwards.

The next three sections or tasks ask you to focus in on the module level, though you will need to keep the programme-level outcomes and assessment map in the back of your mind to ensure alignment. We’ll look at the building blocks that form the basis of each module: the learning outcomes, assessment tasks and learning activities. We’ll be looking to flesh out the initial vision into a more structured pathway that is constructively aligned, asking: how do we define the learning in terms of demonstrable outcomes? how do we design assessment opportunities that allow the learner to demonstrate achievement of those outcomes? how do we create learning activities that support the learner to reach the intended outcomes and succeed in the assessment? For this we often use a ‘backwards design‘ approach, beginning with what we want the learner to know and be able to do at the end of the module, and working backwards.

First in this sequence are the outcomes (what the student should ‘come out with’, or should know or be able to do). These are arguably the most important element of a module, and not (only) because they are required for quality assurance and benchmarking! Outcomes define the parameters of what will be covered, and help the student to understand what’s expected and what will be assessed. We will check the outcomes for each module against three key criteria: language, academic level, and relation to assessment.

Assessment activities will be chosen or reviewed to ensure validity: what’s the best way for a student to demonstrate these outcomes? We’ll also consider how to prepare the students for the assessment (in terms of process as well as content), and how to incorporate peer and self-assessment.

Finally, we’ll begin to consider what kind of learning and teaching will be needed to support the students in achieving the outcomes. We’ll cover this in more depth in the next section.

A note on paperwork: Any design change to a module needs to work within the relevant quality assurance framework. If you’re working on learning outcomes or assessments, these may already be written in your module specification, and making changes to these could require a change of approval. When designing learning activities, you’ll also need to consider the allocation of teaching, learning and assessment hours that currently make up the workload for that module (200 hours for a 20 credit module). Don’t let QA requirements stop you improving things – your Learning Designer or Embedded Quality Officer can help you to understand the requirements for any suggested changes.

This is one in a series of posts about the CAIeRO process. To see the full list, go the original post: De-mystifying the CAIeRO.

Need a CAIeRO? Email the Learning Design team at LD@northampton.ac.uk.

CAIeRO workshops are a time-intensive activity, requiring two full days from every member of the team to be most effective. With this in mind, it’s really worth taking the time in advance to agree what the team wants to achieve in that time. The person running the CAIeRO will be a trained facilitator or Learning Designer, and they will always request a pre-CAIeRO meeting, with at least the programme and module leaders but ideally with the whole team.

CAIeRO workshops are a time-intensive activity, requiring two full days from every member of the team to be most effective. With this in mind, it’s really worth taking the time in advance to agree what the team wants to achieve in that time. The person running the CAIeRO will be a trained facilitator or Learning Designer, and they will always request a pre-CAIeRO meeting, with at least the programme and module leaders but ideally with the whole team.

In the pre-CAIeRO meeting we will cover a range of topics including:

- Background to the programme. We’ll need an idea of what the course is about, who the tutors are, who the learners are, mode of delivery etc.

- Why do you need a CAIeRO? We’ll discuss any goals or challenges identified by the programme team that need to be addressed, and also any upcoming QA processes (validation, PSR) that need to be considered.

- What do you know about CAIeRO? We’ll give you an overview of what you can expect, what’s expected of you, and the deliverables.

- What skills and resources do we have available? We’ll review what experience the team has of course design, of teaching on the course, of delivering in the chosen mode, of using NILE etc.

- Who (else) needs to be there? We need at least all the staff on the teaching team. This means those who lead and teach on the modules under review, and ideally also those who teach the other modules in that year or programme. This helps promote a consistent experience from the student perspective, and also allows the shared vision and skills developed to be disseminated to other modules where appropriate. We will also need at least one ‘reality checker’ from outside the team (more on that later). But in order to get the design right, we might also want input from other stakeholders… Students? Academic Librarian? Learning Technologist? Embedded Quality Officer? CfAP? Critical friend? External Examiner? Employer?

- Logistics. When* and where? You’ll need a room with a screen, and with tables for laying out flip chart paper. And although fun, CAIeRO can also be hard work, so don’t forget the coffee and biscuits!

Once we have all the details worked out, your Learning Designer will create a CAIeRO planner document and send out the link to it. This is a working document that we will be using throughout the process. Before the CAIeRO itself, the team can use this document to record their aims for the module, reflections on student feedback, and any ideas or resources they want to include on the day.

*Note: the two days that make up a CAIeRO do not need to be consecutive. There are benefits to keeping the two days together to maintain momentum, but it can also be helpful to leave time in between for reflection, depending on how the team works best. It is important though to put both days in the diary at the beginning. Leaving the second day to be arranged later risks leaving the work half done, despite the best of intentions…

This is one in a series of posts about the CAIeRO process. To see the full list, go the original post: De-mystifying the CAIeRO.

Need a CAIeRO? Email the Learning Design team at LD@northampton.ac.uk.

“I keep hearing about this CAIeRO thing, but I don’t really know what it is…”

CAIeRO stands for “Creating Aligned Interactive educational Resource Opportunities”. If you’re wondering, yes, there is a theme here. The acronym was chosen (although not by me) to align with the Northampton Integrated Learning Environment (NILE).

CAIeRO stands for “Creating Aligned Interactive educational Resource Opportunities”. If you’re wondering, yes, there is a theme here. The acronym was chosen (although not by me) to align with the Northampton Integrated Learning Environment (NILE).

So what does it actually mean? Think of it as a Course Design Retreat – a full module CAIeRO is two days away from the phone and the email, to build or re-design taught modules, with support from a range of specialist staff. Every CAIeRO will be different, but broadly speaking the workshop has two aims – to develop the modules themselves, and to help the teaching team to develop their course design skills.

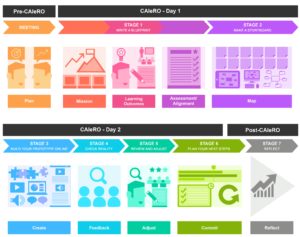

This is the first in a series of blog posts examining the different elements of the CAIeRO course design process. The series will cover all of the key interactions, from the pre-CAIeRO meeting through to follow up activities. It will discuss the tools and techniques used in CAIeRO, and their role in course design.

I hope these posts will provide an insight into the process for those that are new to CAIeRO, as well as a reminder for those who have participated in or facilitated sessions. CAIeRO is a work in progress, and we’d love to hear about your experiences, so please feel free to add your own comments, insights and suggestions.

Links to the posts will be added below as they are published. You can also click on the image to see a visual overview of the CAIeRO process.

Links to the posts will be added below as they are published. You can also click on the image to see a visual overview of the CAIeRO process.

De-mystifying the CAIeRO:

- The pre-CAIeRO meeting

- Programme level CAIeRO

- CAIeRO Stage 1: The blueprint

- CAIeRO Stage 2: The storyboard

- CAIeRO Stages 3-5, let’s get building!

- CAIeRO Stages 6 and 7, planning and reflecting

Need a CAIeRO? Email the Learning Design team at LD@northampton.ac.uk.

For more information about the development of the CAIeRO methodology, research into the use of CAIeRO, and guidance on how to become a facilitator, see the Introduction to CAIeRO page on our ILT website.

A typical module CAIeRO will often start with programme level exercises, such as agreeing or reviewing the mission, ‘look and feel’, and learning outcomes for the programme as a whole. It’s in the interests of the teaching team – and the students – to (re-)use these elements of the programme’s blueprint when designing at module level – it helps to promote coherence and consistency, and to minimise unintentional duplication. But focusing on the module level, while necessary for planning and supporting good learning, can sometimes lead to a fragmented approach over time. Sometimes you need to take a step back to see the bigger picture.

The Learning Design team are often asked to support teams who need to review and make changes at the programme level. As with module CAIeROs, the reasons for this can be many and varied: maybe it’s a new programme or pathway; maybe there have been significant changes in staffing or in the subject area; maybe the team want to respond to specific institutional agendas or to challenges identified in student feedback or grades; maybe it’s just been a long time since the programme was reviewed as a whole and the team want to ensure that iterative changes at the module level haven’t affected the coherence of the award map. Programme level CAIeROs can be as diverse and bespoke as module level ones, but there are some common goals, and as a team we are always refining our toolkit to support them. You may find you use some of the steps below more or less depending on your needs, but this post, along with the Programme Planner developed by our very own Rob Farmer, will give you an idea of some of the approaches available to you.

Before you start: (Re)establishing consensus

The programme ‘blueprint’

As always we suggest you start by defining the intended outcomes, if you don’t have these already. Although programme outcomes are slightly different to module outcomes, because they are not directly assessed, many of the same principles still apply. They need to be aligned with national quality standards (e.g. the FHEQ and Subject Benchmark Statements), and with any relevant Professional, Statutory and Regulatory Body (PSRB) requirements if the programme is accredited – and of course they have to make sense to non-experts, including students and employers. Once you have your programme outcomes, you can start thinking about breaking them down into chunks of learning that will form your taught modules – or, for existing programmes, reviewing how well they map to the modules you already have in place. Do you need to add, remove, combine or split anything?

Sequencing learning

Taking a programme level perspective allows you to plan the development of understanding and skills across a larger timeframe, to make sure that the scaffold is sound and your students aren’t missing a foundation piece when they reach the higher levels. To get the sequence right, you can storyboard your programme using a range of tools, from paper and post-its to Powerpoint or Popplet. Move the pieces around until the order seems logical, and think about whether each piece needs to be ‘short and fat’ (intensive) or ‘long and thin’. At this stage you might want to consider the placement of elements that are more complicated to schedule, like placements and trips, as well as those over which you have no control, like holidays and closed days.

Taking a programme level perspective allows you to plan the development of understanding and skills across a larger timeframe, to make sure that the scaffold is sound and your students aren’t missing a foundation piece when they reach the higher levels. To get the sequence right, you can storyboard your programme using a range of tools, from paper and post-its to Powerpoint or Popplet. Move the pieces around until the order seems logical, and think about whether each piece needs to be ‘short and fat’ (intensive) or ‘long and thin’. At this stage you might want to consider the placement of elements that are more complicated to schedule, like placements and trips, as well as those over which you have no control, like holidays and closed days.

Mapping assessment and feedback

It can be really useful to overlay your assessments on to your programme storyboard, to give you an idea of the mix of assessment activity and also to identify any deadline and marking ‘bottlenecks’. Programme leaders will usually collate details of the summative assessments across a programme, because this information is required for processes like validation, but we would encourage you to do this for your formative assessment opportunities too. This will allow you to easily see the turnaround time and where students will receive their feedback – and to identify whether it is timely enough to be useful for the next summative task! If you don’t know yet how your modules will be assessed, make a note to come back to this step, or keep a ‘work in progress’ version that you can update with more detail as you go on.

Key skills and ChANGE skills

Programme design can be a complex business – and this is before you even get in to the details of the individual modules! We recommend that teams who have a lot to do at the programme level leave at least a full day for this type of work, before moving on to the module level CAIeROs.

This is one in a series of posts about the CAIeRO process. To see the full list, go the original post: De-mystifying the CAIeRO.

Need a CAIeRO? Email the Learning Design team at LD@northampton.ac.uk.

Great learning design and quality assurance are two sides of the same coin. When you make changes to a module or programme, there are a range of QA procedures that might apply, and it helps to understand how these processes interlink – particularly when planning ahead.

Great learning design and quality assurance are two sides of the same coin. When you make changes to a module or programme, there are a range of QA procedures that might apply, and it helps to understand how these processes interlink – particularly when planning ahead.

New programmes or modules

When writing a new module or programme, a CAIeRO workshop can help you with everything from writing the learning outcomes, to choosing the assessment and creating the learning activities. The first day of the workshop will help you set the foundations, and the second day helps ensure these are workable in practice.

New programmes and modules are subject to validation, and as part of this process you will be required to write a rationale for the new offering. The planning work you do in the CAIeRO can help you complete this, as it includes consideration of strategic goals, the student experience, and resource and training requirements. The CAIeRO process can also help you firm up your curriculum documentation (also required for validation), and make decisions about the allocation of teaching and learning hours, assessment strategy and more. In addition to documentation, the CAIeRO can help you get started creating sample teaching materials, which are required for validation of distance learning programmes.

At the University, many validations can be completed online, but some (particularly those involving PSRBs) require a validation event. For these programmes, validations usually take place in the Spring term. For a new programme starting in September, you should aim for validation early in the term to allow the maximum possible time for development of the course materials (if you want the course to start the following January, you might aim for validation later, in March or April). This means you should be scheduling your CAIeRO in the previous Autumn term.

For more on the validation process, see the validation page of the website, which has information and links to the handbook..

Periodic subject reviews

PSRs are a chance to reflect on what has worked well in your teaching over the previous five years. It is also a great opportunity to use those reflections to define the future direction of the programmes involved. The CAIeRO process can be used to support this process in a number of ways: as a ‘health check’ or review of a programme; to target specific issues you may have identified; and/or to plan how to implement changes you’d like to make.

PSRs are a chance to reflect on what has worked well in your teaching over the previous five years. It is also a great opportunity to use those reflections to define the future direction of the programmes involved. The CAIeRO process can be used to support this process in a number of ways: as a ‘health check’ or review of a programme; to target specific issues you may have identified; and/or to plan how to implement changes you’d like to make.

For PSR you will be required to submit a Self-Evaluation Document (SED). This document will ask you to reflect on things like alignment with frameworks and standards, the currency of the curriculum and student achievement and feedback. All of these elements can be considered within the CAIeRO process, to help you complete the SED form and prepare for any questions during the PSR event.

At the University, PSRs usually take place in the Autumn term, and the documentation is submitted in advance. CAIeROs for PSR can be scheduled at any point in the year (although you may want to note the Change of Approval guidance below when considering timing).

For more on the PSR process, see the PSR page on the website, which has information and links to the handbooks.

Ongoing review of delivery

Of course, adjusting and adapting your teaching and assessment practice happens all year round, and is not dependent on big events like those listed above. You might have taken over a module or programme, or be considering a more blended approach, or just want to try a new idea you’ve heard about. You can book a CAIeRO for issues like this at any time in the year, but you should be conscious of timing the implementation of these changes, and the possible impact on the student experience.

Of course, adjusting and adapting your teaching and assessment practice happens all year round, and is not dependent on big events like those listed above. You might have taken over a module or programme, or be considering a more blended approach, or just want to try a new idea you’ve heard about. You can book a CAIeRO for issues like this at any time in the year, but you should be conscious of timing the implementation of these changes, and the possible impact on the student experience.

Wherever possible, you should avoid making big changes that will affect current delivery of a module or programme part way through. In addition to this, for level 5 and 6 modules, be aware that students need to know what to expect when they make their module choices. Any changes made after students have chosen the module should be made in consultation with those students.

Changes to existing modules and programmes are achieved through the Change of Approval process, which recognises three levels of change (based on degree of impact). Type B and C changes (more substantial than Type A) must be submitted well in advance of the proposed delivery, and for levels 5 and 6, in advance of the publication of module information to students. For 2015/16 delivery, the deadline for change of approvals for these modules is 13 January (for levels 4 and 7, the deadline is May).

For more on this process, see the Change of Approval page on the website, which has information and links to the handbooks.

In 2003, Richard Winter wrote a piece for the Guardian in which he listed some problems than can occur when essays are the primary tool used to assess what, and how much, students have learned. Winter claimed that the essays students write often show evidence only of surface learning, rather than deep learning, and that the use of essays for assessment was partly to blame for this. Personally speaking, I really like the essay. I find it stimulating, challenging, and an opportunity to examine and learn in great detail and depth. However, regardless of how much one might like the essay, sometimes it could be useful to provide students with a friendly way in to academic writing, especially for first-year undergraduates or those returning to education after a break, and this is where patchwork text assessment comes in.

In 2003, Richard Winter wrote a piece for the Guardian in which he listed some problems than can occur when essays are the primary tool used to assess what, and how much, students have learned. Winter claimed that the essays students write often show evidence only of surface learning, rather than deep learning, and that the use of essays for assessment was partly to blame for this. Personally speaking, I really like the essay. I find it stimulating, challenging, and an opportunity to examine and learn in great detail and depth. However, regardless of how much one might like the essay, sometimes it could be useful to provide students with a friendly way in to academic writing, especially for first-year undergraduates or those returning to education after a break, and this is where patchwork text assessment comes in.

The basic idea is that rather than choosing one or two major points of assessment, the students submit multiple short pieces of writing on a regular basis (perhaps in the form of an academic blog or journal) which are then ‘stitched together’ with a final summary, evaluation or reflective commentary. The learning outcomes remain the same, the word count is not altered, and the final submission deadline stays as it is: the difference is that the writing is built up over a longer period of time, in which the students complete many short, directed writing tasks. The writing tasks could be similar or varied, and could be shared for peer-review or kept private. Tutors could review the writing tasks at one or two specific intervals in order to provide formative feedback, or could simply mark everything at the end of the process.

Dr. Craig Staff (Senior Lecturer in Fine Art) and Rob Farmer (Learning Designer) are currently conducting research into patchwork text assessment with students in the School of The Arts. The purpose of the research is to study the attitudes of students to this type of assessment, to look at the quality of the writing they produce, and to determine the staff workload implications when assessing the patchwork texts. The project is due to run over three academic years (2013/14, 2014/15, 2015/16), and will involve around 300 students from levels four to six. Interim findings from the students who undertook the patchwork assessments in 2013/14 clearly showed that it would be worthwhile continuing with the project.

Find out more …

Read Richard Winter’s 2003 Guardian article ‘Alternative to the Essay’

Visit the patchwork text pages of Richard Winter’s website

Visit the Digitally-enhanced Patchwork Text Assessment (DePTA) JISC project website

Student perceptions of their learning and engagement in response to the use of a continuous e-assessment in an undergraduate module.

Student perceptions of their learning and engagement in response to the use of a continuous e-assessment in an undergraduate module.

Naomi Holmes, School of Science and Technology

Dr. Naomi Holmes (School of Science and Technology) undertook the use of low-stakes continuous weekly summative e-assessment with a cohort of level 5 (2nd year) students. Biggs and Tang (2011) state that it is assessment and not the curriculum that determines how and what students learn. Learning needs to be aligned with assessment as much as possible to increase engagement, even if the result is that the student is “learning for the assessment”, and therefore accreditation. With this in mind the use of low-stakes weekly assessments was undertaken to help support learning (formative), and lead to accreditation (summative). Results show that both physical and virtual engagement with this (optional) module, and students’ learning and understanding of the subject increased because of this method of assessment.

Recent Posts

- Staff GenAI Survey Report 2024

- Blackboard Upgrade – May 2024

- Learning Technology Team Newsletter – Semester 2, 2023/24

- Getting started with AI: A guide to using the Jisc Discovery Tool’s new AI question set.

- Blackboard Upgrade – April 2024

- Exploring the Role of GenAI Text to Enhance Academic Writing: A Conversation with Learning Development Tutor Anne-Marie Langford.

- Interview with the University’s Digital Skills Ambassador

- Blackboard Upgrade – March 2024

- Case study: GenAI in BA Fashion, Textiles, Footwear & Accesories 2024

- Exploring the Educational Potential of Generative Artificial Intelligence: Insights from David Meechan

Tags

ABL Practitioner Stories Academic Skills Accessibility Active Blended Learning (ABL) ADE AI Artificial Intelligence Assessment Design Assessment Tools Blackboard Blackboard Learn Blackboard Upgrade Blended Learning Blogs CAIeRO Collaborate Collaboration Distance Learning Feedback FHES Flipped Learning iNorthampton iPad Kaltura Learner Experience MALT Mobile Newsletter NILE NILE Ultra Outside the box Panopto Presentations Quality Reflection SHED Submitting and Grading Electronically (SaGE) Turnitin Ultra Ultra Upgrade Update Updates Video Waterside XerteArchives

Site Admin