Dr Craig Staff, Reader in Fine Art, and Robert Farmer, Learning Technology Manager, have published an article in the latest edition of Art, Design and Communication in Higher Education, a special edition on the theme of democratizing knowledge in art and design education. According to the journal’s editor, Professor Susan Orr, Dean of Learning/Teaching & Enhancement at University of the Arts London “The authors make a strong argument that the patchwork text approach works well within a creative education context, where experimentation and risk-taking are valued.”

The article itself presents the findings from a four-year project designed to gather undergraduate Fine Art students’ perceptions of replacing an essay with a Patchwork Text Assessment (PTA), a form of assessment in which a series of self-contained, thematically related patches are written at regular intervals over a series of weeks or months and are then stitched together with a final meta-patch exploring the unity and interrelatedness of the individual patches.

On completion of the PTA, students were asked a series of questions about their experiences, and analysis of their responses showed that they had found completing the PTA more difficult, more enjoyable and more rewarding than writing an essay. Importantly, there were no suggestions that the PTA had dumbed down assessment practices, nor was there an increase in the workload of the academic staff supporting and assessing the PTA.

The full article can be viewed and downloaded here: https://doi.org/10.1386/adch_00003_1

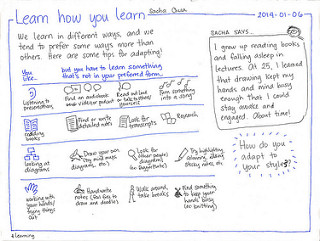

We’ve written a few posts about learning styles in the past, and an important letter in yesterday’s Guardian added yet more support to the anti-learning styles side of the argument. Thirty academics signed a letter to the Guardian calling for teachers to end the use of learning styles and to make more use of evidence-based practices instead. Regarding the use of learning styles, the letter said that they were “ineffective, a waste of resources and potentially even damaging as … [they] can lead to a fixed approach that could impair pupils’ potential to apply or adapt themselves to different ways of learning.”1

You can read the entire letter here: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2017/mar/13/teachers-neuromyth-learning-styles-scientists-neuroscience-education

References

1. Sally Weale (2017) Teachers must ditch ‘neuromyth’ of learning styles, say scientists

“Now is the time of the essay film.” So said the film-maker Mark Cousins to the Guardian’s Charlotte Higgins in 2013. This realisation came to Cousins during the making his film, The First Movie, which was filmed in the Kurdish region of Iraq in 2009. One major problem that Cousins faced when making the film was that because the region was so dangerous, there were no cinematographers who were willing to work on the film. This did not stop Cousins though, and he decided to make the film himself using tiny, handheld cameras. What may have been perceived as an insurmountable obstacle was not only overcome, but actually created new ways of working and a new sense of freedom for Cousins. As he says,

“Now is the time of the essay film.” So said the film-maker Mark Cousins to the Guardian’s Charlotte Higgins in 2013. This realisation came to Cousins during the making his film, The First Movie, which was filmed in the Kurdish region of Iraq in 2009. One major problem that Cousins faced when making the film was that because the region was so dangerous, there were no cinematographers who were willing to work on the film. This did not stop Cousins though, and he decided to make the film himself using tiny, handheld cameras. What may have been perceived as an insurmountable obstacle was not only overcome, but actually created new ways of working and a new sense of freedom for Cousins. As he says,

“‘What I used to hate about filming is that I’d want to get up before dawn in Calcutta and film the sunrise. But you’d have to go knocking on the door of the director of photography, who’s sleeping, and say, ‘Please can you get up?’ This tiny camera, no bigger than a mobile phone, has become like a pen, he says: he can work alone, with the freedom of a prose essayist. ‘Now is the time of the essay film: that way of taking an idea for a walk.’”

Of course, the idea of the essay film, or cine essay as some film-makers like to call it, is not new, it’s just that it’s taken some time for technology to get to the point where the video camera and editing equipment are truly as portable and lightweight as the pen and the notebook. The idea of the film camera as a pen (or camera stylo as it is sometimes known) was introduced by Alexandre Astruc in his 1948 essay The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La Camera-Stylo.

Astruc was one of many film theorists who had high expectations about the potential of cinema to go beyond mere entertainment and spectacle, and who believed that cinema was capable of expressing complex, philosophical thought. He believed that cinema could be the intellectual equal of the novel or the philosophical essay, and nearly seventy years ago he said,

“Maurice Nadeau wrote in an article in the newspaper Combat: ‘If Descartes lived today, he would write novels.’ With all due respect to Nadeau, a Descartes of today would already have shut himself up in his bedroom with a 16mm camera and some film, and would be writing his philosophy on film: for his Discours de la Methods would today be of such a kind that only the cinema could express it satisfactorily. […] From today onwards, it will be possible for the cinema to produce works which are equivalent, in their profundity and meaning, to the novels of Faulkner and Malraux, to the essays of Sartre and Camus.”

But was Astruc right? Well, the philosopher John Gray might agree that he was. Indeed, Gray might well go further and say that the film-makers of today are doing a better job than academic philosophers in exploring some of the key philosophical issues of our time. In his review of a collection of Nietzsche’s lectures on education, entitled Anti-Education: On the Future of Our Educational Institutions, Gray tells us that,

“Justin Kurzel’s film of Macbeth presents an uncompromisingly truthful vision of the human situation unlike anything in the academic study of the humanities at the present time. The Wire and Breaking Bad explored the contradictions of ethics with a rigour and realism that is lacking in the baroque disquisitions on justice and altruism that occupy philosophers. Amazon’s version of Philip K Dick’s The Man in the High Castle is a more compelling rendition of the slipperiness of consensus reality than you will find in any number of turgid volumes of critical theory.”

Of course, neither Gray nor anyone else is saying that one form of expression is, per se, better than another. And Astruc’s point about Descartes is deliberately designed to be provocative and polemical. To argue that the cine essay is better than the essay is as pointless as trying to argue which account of the Holocaust is the best; Claude Lanzmann’s film Shoah, Primo Levi’s memoir If This Is A Man, or David Cesarani’s book The Final Solution. The point is that the essay and the cine essay can present different perspectives on the same subject, and will reveal different things about that subject through the specificity of the different media.

But the question we need to ask is what does this have to do with teaching and learning? Well, if we are persuaded that film is capable of expressing complex, philosophical thought, and if we are also persuaded that the equipment with which to make films is small, portable and already in the hands of many students, then it may follow that, on occasion, we might want to ask their students to submit a cine essay instead of an essay. And this is where the work of LSE lecturer Professor William A. Callahan comes in. Professor Callahan leads a course in Visual International Relations at LSE, and his students are regularly assessed via documentary films. The reason for this is, he says, that

“Documentaries encourage students to work collaboratively, reinforce concepts learnt, and generate new knowledge as well as resources that can be used by future students. Allowing students to create knowledge (and materials) together seems an excellent practice, so it’s a surprise it isn’t more widespread.”

Professor Callahan’s decision to introduce documentary making as an assessed component of his course came from his own experiences of making films, after he took a short course in documentary film-making and started making his own films. As he found out from his own experiences as a filmmaker, the camera is capable of recording the

“nonlinguistic and nonrepresentational aspects of knowledge: the laughs, sighs, shrugs, cringes and tears that are provoked in the on-camera interview process, which then can be edited into an engaging set of images that, in turn, can produce laughs, cringes and tears in the film’s audience.”

And it is this ability to convey meaning and to persuade through the use of images that he wants his students to understand when they take his course.

“That’s what the students get by the end of the course. They know how to write an essay but by the end of the course they should know how to, not just convince us with their academic, rational thinking, but move us through their images, move us emotionally.”

While it may not be possible to get access to the kind of equipment used by Callahan and his students, mobile phone manufacturers are continually trying to persuade us of the high quality of the cameras in their phones. Apple’s Shot on an iPhone campaign was a major part of the iPhone 6 release, Samsung have their own Captured on a Samsung S7 gallery, and most of the other big mobile manufacturers make great claims about the quality of the cameras in their phones. And there are now film festivals entirely dedicated to screening films shot on mobile phones, including the Mobile Motion Film Festival and the Mobile Film Festival, which is running for the twelfth time in 2017. Given than many of these devices are already in the pockets of our students, is now a good time to consider the cine essay?

Tips and recommendations

1. Probably the most important recommendation for anyone thinking about asking their students to submit a film or documentary, is firstly to have a go a making a film yourself. If you don’t have your own film-making gear, the LearnTech team can lend you an iPad so that you can have a go at making a film. The LearnTech iPads come with iMovie (a film editing program), so you can film and edit on the iPad. You can also borrow an iPad tripod from the LearnTech team.

2. If you don’t know where to start there are some usful introductory guides about making films on mobile devices. This one from Tom Barrance is worth a look: http://learnaboutfilm.com/making-a-film/filmmaking-iphones-ipads/

3. You can learn how to use iMovie to edit your film by signing up to the course on Lynda.com. All staff at the University can access Lynda courses for free (unfortunately students cannot access Lynda courses for free at the present time). The iMovie on iPad course is here: https://www.lynda.com/iMovie-tutorials/iMovie-iOS-Essential-Training/165441-2.html

4. If you can get a few people together then it may be possible to run a one day workshop for staff who are interested in learning how to film and edit using iPads. If this is something you’d like to do, feel free to email me: robert.farmer@northampton.ac.uk

5. This one is important. While the LearnTech team can lend iPads to members of staff for short periods of time, there is nowhere in the University where students can borrow film-making equipment (unless they are film/media/photography students). Thus, any film or documentary assignment will rely on students having their own equipment. Although most students do have smartphones, not all will have one, so you may want to make any film assessment into group projects.

6. If you do decide to alter an assessment to make it a film submission you will need to have your module re-validated. This is not an especially onerous process, but you may like to ask a Learning Designer to help you with this. Learning Designers can help you to design a suitable moving image assessment and can check through your learning outcomes to ensure that new assessment aligns with the learning outcomes. To change a module for the forthcoming academic year, you will ideally need to be ready to submit the revalidation paperwork in the January of the current academic year.

7. Prior to making any changes to a module and introducing a film/documentary assignment, it may be worthwhile asking your current students what they think of the idea.

8. Film-making can be quite time-consuming, so it might be best to err on the side of caution and keep the film length short, especially if it is the first time your students have sumitted a film. Five minutes is plenty of time, and could easily equate to 2.5 assessment units in a group project with two or three students per group. Again, a Learning Designer can help you with this process.

9. NILE fully supports student moving image submissions. Students can upload their completed films to http://video.northampton.ac.uk and can submit them to assignment submission points in NILE. Staff can view these film submissions directly in NILE without having to download them. Staff can also use http://video.northampton.ac.uk to upload their own films and embed them into NILE modules.

10. If you find that you really start to enjoy film-making and want to take things to the next level, you can learn all about making films from one of the great modern masters, Werner Herzog: https://www.masterclass.com/classes/werner-herzog-teaches-filmmaking

More information about William Callahan

If you would like to know more about William Callahan’s approach you can read about it here: http://lti.lse.ac.uk/lse-innovators/william-a-callahan-visual-international-politics-student-movies/

You can also watch him talking about it here: https://vimeo.com/140330542

You can view his films and the films of his students here: https://vimeo.com/billcallahan

And you can read his paper, The visual turn in IR: documentary filmmaking as a critical method here: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/64668/

Useful Links*

21 tips, tricks and shortcuts for making movies on your mobile: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/feb/12/21-tips-tricks-and-shortcuts-for-making-movies-on-your-mobile

10 tips for editing video: http://blog.ted.com/10-tips-for-editing-video/

7 interviewing tips for video storytellers: http://blog.ed.ted.com/2016/11/23/7-interviewing-tips-for-video-storytellers/

How our mobile-only TV package made the network news: http://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/academy/entries/c1b5506f-c627-417e-8958-ca36aaf86f01

Instead Of A Book Report, My Students ‘Wrote’ A Video: http://www.teachthought.com/the-future-of-learning/technology/instead-of-a-book-report-my-students-wrote-a-video/

6 Steps to Media Creation in the Classroom: http://dailygenius.com/6-steps-media-creation-classroom/

* Many thanks indeed to Belinda Green for the useful links.

The Quick Overview:

• Where students need to carry out online surveys, and where academic staff do not have a preference as to which tool the students use, we recommend eSurv: http://esurv.org

• A tutorial video explaining how to use eSurv is also available here: http://bit.ly/esurv-tutorial

One area where students sometimes come unstuck with their research projects is when they try to extract data from the free online survey tool they have used. While it is often easy to create a simple online survey for free, and easy for a limited number of respondents to take part in the survey, it is not always so easy for the researcher to access their data.

There are a large number of free online survey tools available for use, and choosing the most appropriate one is not always easy. In almost all cases, accessing the full-functionality of the survey tool is not free. For example, the free version of the survey tool may be limited by number and type of questions available (a maximum of ten questions, for example, and only basic questions). It may also be limited to a maximum number of responses (fifty responses per survey, for example). Another common restriction is to limit access to the survey data, and not to allow the researcher to download the data for analysis in a statistical package. While all these restrictions can be overcome by paying a monthly subscription to the survey tool provider, students often feel rather cheated when they find out that it will cost them, in some cases, £60 to download their data for analysis in SPSS. They often feel especially annoyed when they find out that if they chosen different tool they could have had free access to their data.

As part of a recent University of Northampton URB@N project, Paul Rice, Phil Oakman, Clive Howe and Rob Farmer decided to find out whether there was a genuinely free online survey tool out there somewhere. And they decided to make things more difficult by trying to find one that was also easy to use and that stored data in a way that was compliant with the UK Data Protection Act. The good news is that they found one!

If you would like to find out more then you can read all about it in their paper published in the journal MSOR Connections: https://journals.gre.ac.uk/index.php/msor/article/view/311

We came across this great resource recently, from the Teaching Excellence and Educational Innovation Center at Carnegie Mellon University. It’s designed to help academics solve teaching problems through a three-step process:

We came across this great resource recently, from the Teaching Excellence and Educational Innovation Center at Carnegie Mellon University. It’s designed to help academics solve teaching problems through a three-step process:

- Step 1: Identify a PROBLEM you encounter in your teaching.

- Step 2: Identify possible REASONS for the problem

- Step 3: Explore STRATEGIES to address the problem.

To access the site, click on the image, or use this hyperlink: https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/solveproblem/index.html

So argues Dr Chris Willmott, Senior Lecturer in Biochemistry at the University of Leicester.

In a recent article for Viewfinder, entitled Science on Screen, Dr Willmott discusses his use of clips from films and television programmes in his university bioscience teaching. Dr Willmott considers a number of ways in which clips from science programmes and popular films (even those which get the science woefully wrong) can be used as teaching aids, all of which are designed to promote engagement with the subject, and which can be incorporated into a flipped learning session.

He categorises his use of clips from films and television programmes in the following way, which you can read more about in his article:

- Clips for illustrating factual points

- Clips for scene setting

- Clips for discussion starting

Obviously not all science programmes get things right, but rather than being off-putting, this can be a great starter for a teaching and learning session. In the following example, Dr Willmott explains how he makes use of a clip in which Richard Hammond ‘proves’ that humans can smell fear:

Students are asked to watch the clip and keep an eye out for aspects of the experiment that are good, and those features that are less good. These observations are then collated, before the students are set the task of working with their neighbours to design a better study posing the same question.

If you’re interested in using visual content to aid the teaching of science then there are an increasing number of visual resources available. Dr Willmott mentions the Journal of Visualised Experiments in his article, a journal which is now in it’s tenth year, and which has over 4,000 peer-reviewed video entries. It’s a subscription only journal, and we don’t have a subscription, but if it looks good and you speak nicely to your faculty librarian then who knows what might be possible!

A resource that we do subscribe to is Box of Broadcasts, a repository of over a million films and television programmes. Accessible to academics and students (as long as they are in the UK), BoB programmes are easily searched, clipped, organised in playlists, and linked to from NILE. Plenty of material from all your science favourites such as Brian Cox, Iain Stewart and Jim Al-Khalili and even the odd episode from classic science documentaries like Cosmos and The Ascent of Man.

A free, and very high quality visual resource is the well known Periodic Table of Videos, created by Brady Haran and the chemistry staff at the University of Nottingham. Also of interest to chemists (but not free) are The Elements, The Elements in Action, and the Molecules apps developed by Theodore Grey and Touch Press. Known collectively as the Theodore Grey Collection, these iOS only apps may end up being the best apps on your iPad.

Not visual at all, but still very good, is the In Our Time Science Archive – hundreds of free to download audio podcasts from Melvyn Bragg and a wide range of guests on many, many different scientific subjects from Ada Lovelace to Absolute Zero.

We recently posted a fairly lengthy blog entry about the myth of learning styles in education. The blog post was entitled ‘Question: What’s Your Preferred Learning Style?’ and it looked in some detail at the evidence against the widespread belief that students learn better when presented with information that is in their preferred learning style.

The TEDx video below is highly recommended for anyone with an interest in learning styles. In the video, Tesia Marshik, Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of Wisconsin La Crosse, outlines some of the major arguments against learning styles and explains why, even though such beliefs are mistaken, they are so widely held.

And a belief in preferred learning styles is not the only mistaken belief about learning that is widely held by educators … for more on this see our earlier post ‘Neuromyths in Education’.

Click on the image below to watch the video …

by Robert Farmer and Paul Rice

It’s no easy thing to create an interesting, engaging and effective educational video. However, when developing educational presentations and videos there are some straightforward principles that you can apply which are likely to make them more effective.

The following videos were created for our course, Creating Effective Educational Videos, and will take you through the dos and dont’s of educational video-making.

1. How not to do it!

This short video offers a humorous take on how not to make great educational videos.

- Prof. Oliver Deer discusses his approach to making educational videos: https://youtu.be/cKXx9GkeGGQ

2. Understanding Mayer’s multimedia principles

This 20 minute video outlines Richard Mayer‘s principles of multimedia learning and provides practical examples of how these principles might be applied in practice to create more effective educational videos.

- A Practical Guide to Mayer’s Multimedia Principles: https://youtu.be/m0GMZgaC7gM

3. Applying Mayer’s mutimedia principles

Because much of Mayer’s work centres around STEM subjects (which typically make a lot of use of diagrams, charts, tables, equations, etc.) We spent some time thinking about how to apply his principles in subjects which are more text based. To this end, we recorded a 12 minute video lecture which is very on-screen text heavy in which we tried to make use of as many of Mayer’s principles as possible.

- Are we ever justified in silencing those with whom we disagree? https://youtu.be/Dyu94dH2aeo

4. Understanding what students want, and don’t want, from an educational video

Given the current popularity of educational videos, and given the time, effort and expense academics and institutions are investing to provide educational videos to students, we thought that it was worthwhile to evaluate whether students actually want and use these resources. You can find the results of our investigation in our paper:

- Rice, P. and Farmer, R. (2016) Educational videos – tell me what you want, what you really, really want. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, Issue 10, November 2016. Available from: https://journal.aldinhe.ac.uk/index.php/jldhe/article/view/297

5. Further reading

Mayer, R. (2009) Multimedia Learning, 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press.

https://www.cambridge.org/gb/academic/subjects/psychology/educational-psychology/multimedia-learning-2nd-edition

Rice, P., Beeson, P. and Blackmore-Wright, J. (2019) Evaluating the Impact of a Quiz Question within an Educational Video. TechTrends, Volume 63, pp.522–532.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-019-00374-6

The Learning Design team recently met up with Terry Neville (Chief Operating Officer) and Jane Bunce (Director of Student and Academic Services) to discuss a number of Waterside related issues. Among the subjects discussed were the teaching of large cohorts, timetabling, the working day and the academic year. We video recorded our discussion, and it is now available to view in the ‘Waterside Ready’ section of the staff intranet.

The Learning Design team recently met up with Terry Neville (Chief Operating Officer) and Jane Bunce (Director of Student and Academic Services) to discuss a number of Waterside related issues. Among the subjects discussed were the teaching of large cohorts, timetabling, the working day and the academic year. We video recorded our discussion, and it is now available to view in the ‘Waterside Ready’ section of the staff intranet.

Also available in the same location are three videos from Ale Armellini (Director of the Institute of Learning and Teaching) on the subject of getting ready for Waterside, and one video each from Simon Sneddon and Kyffin Jones, both senior academics, who discuss how they have been preparing for the move to Waterside.

Answer: It doesn’t matter!

Want to know why? Then read on …

The One-Minute Overview

Students don’t really learn better when receiving information in their preferred learning style. Not only is it misleading to encourage them to believe that they do, but it may impair their ability to learn if they think that they have a learning style in which they learn best. However, this does not mean that educators should not use a variety of approaches in their teaching and learning, because students learn best when encouraged to learn in a variety of different ways.

In short, if you’ve been using a variety of approaches to teaching and learning because you wanted to be inclusive and to do something for the visual learners, something for the auditory learners and something for the kinaesthetic learners then that’s great – there’s no problem with that. What the research is suggesting is that you shouldn’t try to get students to figure out what their preferred learning style is and then to suggest that they limit their learning to that style, because that’s not helpful and may be damaging. What is good pedagogy is to vary your approach to teaching and learning because everyone learns better when they learn in lots of different ways.

If you’d like a short and tweetable anti-learning styles quote to back this up, then let me suggest this one from Philip Newton’s 2015 paper ‘The Learning Styles Myth is Thriving in Higher Education’.

The existence of ‘Learning Styles’ is a ‘neuromyth’, and their use in all forms of education has been thoroughly and repeatedly discredited

The Long Article

Introduction

Let me introduce my nightmare learner to you. A scruffy-looking mature student, bearded and bespectacled, he’s been preparing to start his degree by learning about how he learns best, and he introduces himself to you as follows:

“Hi, my name is Rob, and I’ll be studying with you for the next three years. I’ve spent a lot of time analysing the way I learn, so what I’ll need from you, my lecturer, is as follows. I’m an auditory learner, so I’ll need all my material from you in podcast form. I’m also left-brain dominant, so please don’t begin from the big picture and work down to the detail, as that will confuse me and I’ll never learn – I need it the other way around please. And please remember that left-brain learners need logic, rules, facts, sequence and structure in order to learn. Also, I’m an ISTJ according to Myers-Briggs, a Concrete-Sequential learner according to the Mind Styles Model, and a Theorist according to Honey and Mumford, so please bear that in mind when preparing my personalised learning materials. Lastly, and I don’t know how relevant this is, but my star sign is Taurus, so I am loyal and reliable, but can be stubborn and inflexible too. You know, I’m really looking forward to the next three years, and I know that if I’m presented with learning materials that are perfectly suited to my learning style I’ll be able to learn anything.”

This chap is clearly preposterous, and is profoundly confused about the nature of learning. I can say that because he’s me – or, at least a version of me, but one who has been taught that if learning is difficult and is taking too much effort then it’s probably because of a mismatch between the learning materials and one’s own learning style, not because it actually does take some degree of effort to learn new things.

Nevertheless, some things do genuinely impede learning. If someone is worried or anxious about something, if they are very hungry or very tired, if they’re in physical discomfort, if the content is too advanced, if they can’t hear what’s being said or see what’s being shown, or if they’re demotivated for whatever reason then they are not going to be able to learn well, if at all. But do we really want to say that someone will struggle to learn if they’re a kinaesthetic learner and have been given a podcast to listen to? Do we really want to handicap our students by telling them that learning is so specific and individual that they can only learn effectively in one way? Why not free our students by telling them that they all have these amazing brains which can and do learn in many, many different ways? Not only that, but that by embracing a wide range of different approaches to learning they will actually learn better.

Let’s look at the issue from another angle. Why don’t students learning to be doctors learn about phrenology or about the four humors? Why don’t biology students learn about the theory of maternal impression? Why don’t chemistry students learn about phlogiston or about the transmutation of base metals into gold? Why don’t physics students learn about caloric or the emitter theory of light? The simple answer to this question is because none of these ideas has any basis in fact. While they might be taught on course covering the history of science, they would no more be taught as scientific fact than would the geocentric model of the solar system. These are all theories which have been consigned to the scientific dustbin, and rightly so.

As far as education is concerned, we are not without our theories and ideas which we have consigned to the educational dustbin. Brain Gym is already in the dustbin, and has been for some time1, but another idea that should have been consigned to the dustbin of educational ideas is the notion of preferred learning styles. However, over 90% of UK teachers still believe the following statement to be true: ‘Individuals learn better when they receive information in their preferred learning style (for example, visual, auditory or kinaesthetic).’2

Should we be using learning styles?

Broadly speaking, the idea behind learning styles is that students have a ‘preferred learning style’ and that students learn best if they are allowed to learn in their the preferred learning style. Some of the more popular learning style theories include VAK, which classifies students as visual, auditory or kinesthetic learners, and Honey and Mumford, which classifies learners as activists, theorists, pragmatists and reflectors.

In his 2004 book, ‘Teaching Today’, Geoff Petty makes the following very reasonable claim:

“There is strong research evidence that ‘multiple representations’ help learners, whatever the subject they are learning. There is much less evidence for the commonly held view that students learn better if they are taught mainly or exclusively in their preferred learning style.”3

A couple of years later, in 2006, in his book ‘Evidence Based Teaching’, Petty went further, and stated that:

“It is tempting to believe that people have different styles of learning and thinking, and many learning style and cognitive style theories have been proposed to try and capture these. Professor Frank Coffield and others conducted a very extensive and rigorous review of over 70 such theories … [and] they found remarkably little evidence for, and a great deal of evidence against, all but a handful of the theories they tested. Popular systems that fell down … were Honey and Mumford, Dunn and Dunn, and VAK.”4 5

Professor Coffield and his colleagues at Newcastle University produced two reports for the Learning & Skills Research Centre in 2004. One was entitled ‘Learning styles and pedagogy in post-16 learning: A systematic and critical review’ and was a hefty 182 page report in which the literature on learning styles was reviewed and 13 of the most influential learning styles models were examined. The second report was entitled ‘Should we be using learning styles? What research has to say to practice’ and was a shorter 84 page report which focused on the implications of learning styles for educators.

Peter Kingston, writing in the Guardian, summarised the findings as follows:

“The report, Should we be using learning styles?, by a team at Newcastle University, concludes that only a couple of the most popular test-your-learning-style kits on the market stand up to rigorous scrutiny. Many of them could be potentially damaging if they led to students being labelled as one sort of learner or other, says Frank Coffield, professor of education at Newcastle University, who headed the research on behalf of the Learning and Skills Development Agency.” 6

The 2004 reports by Coffield et al., appear to have generated a great deal of interest into the now widely discredited (but still widespread and financially lucrative) area of learning styles, and the evidence against learning styles has been steadily building ever since. For example, a 2008 paper by Pashler et al., published in the journal Psychological Science in the Public Interest concluded that:

“The contrast between the enormous popularity of the learning-styles approach within education and the lack of credible evidence for its utility is, in our opinion, striking and disturbing. If classification of students’ learning styles has practical utility, it remains to be demonstrated”7

More recently, Sophie Guterl, writing in 2013 for Scientific American noted that:

“Some studies claimed to have demonstrated the effectiveness of teaching to learning styles, although they had small sample sizes, selectively reported data or were methodologically flawed. Those that were methodologically sound found no relationship between learning styles and performance on assessments.”8

And to bring things even more up-to-date, Philip Newton’s 2015 paper for the journal Frontiers in Psychology paper stated very clearly that:

“The existence of ‘Learning Styles’ is a common ‘neuromyth’, and their use in all forms of education has been thoroughly and repeatedly discredited in the research literature. … Learning Styles do not work, yet the current research literature is full of papers which advocate their use. This undermines education as a research field and likely has a negative impact on students.”9

Conclusion

Learning styles, it appears, are very much in the educational dustbin … it’s just a matter of time before it becomes widely known that that’s where they are. However, even though 93% of UK teachers believe in learning styles, that was still the lowest percentage of all the countries looked at in Howard-Jones’s 2014 paper ‘Neuromyths and Education’. So perhaps the message is slowly getting across in the UK after all.

The seminal reports about learning styles by Coffield et al., are, like all good pieces of academic work, subtle, nuanced, complex, detailed and resistant to clumsy, reductionist, bite-sized soundbites and simplistic conclusions. The reports themselves are no longer available from the LSRC’s website, but can be easily found in PDF format online (just enter the report title into any search engine). For those wanting more of an introduction and overview then Peter Kingston’s summary of the work, published is the Guardian under the title ‘Fashion Victims’, is an excellent place to start. And if you have a copy to hand, pages 30 to 40 of Geoff Petty’s ‘Evidence-Based Teaching’ are well worth a read. If you want to go directly to the originals, the shorter report ‘Should we be using learning styles?’ is the best one to start with, and the set of tables on pages 22 to 35 of the report summarise the pros and cons of the various systems reviewed, giving an overall assessment of each.

For educators, the most useful guidance on learning styles is probably that provided by Petty on page 30 of ‘Evidence-Based Teaching’, where he summarises the advice from Coffield et al., as follows:

1. Don’t type students and then match learning strategies to their styles; instead, use methods from all styles for everyone. This is called ‘whole brain’ learning.

2. Encourage learners to use unfamiliar styles, even if they don’t like them at first, and teach them how to use these.

Notes and References

1. Fortunately, Brain Gym never really made it into universities, but it was popular in schools for some time. Ben Goldacre did much to expose it as pseudoscience, and wrote about it in detail in the second chapter of his book, ‘Bad Science’, and in various Guardian articles dating back to his June 2003 article, ‘Work our your mind’. Goldacre’s 2008 article ‘Nonsense dressed up as neuroscience’ is a good primer on Brain Gym. James Randerson’s 2008 article ‘Experts dismiss educational claims of Brain Gym programme’ summarises the views on Brain Gym of several prominent scientific associations.

2. For more on this, see Paul Howard-Jones’s 2014 paper ‘Neuroscience and education: myths and messages’ or see Pete Etchells’s summary of Howard-Jones’s research: ‘Brain balony has no place in the classroom’.

3. Petty, G. (2004) Teaching Today, 3rd Edition. Cheltenham: Nelson Thornes, pp.149-150.

4. Petty, G. (2006) Evidence Based Teaching. Cheltenham: Nelson Thornes, p.30.

5. Coffield et al., (2004) provide a set of tables listing the pros and cons and a summary of each of the learning styles on pages 22 to 35 of their report, ‘Should we be using learning styles?’ The overall assessment on each of them makes for interesting reading. The best of systems is Allinson and Hayes’ Cognitive Styles Index (CSI), although Hermann’s Brain Dominance Instrument (HBDI) is also well reviewed.

6. Kingston, P. (2004) Fashion victims: Could tests to diagnose ‘learning styles’ do more harm than good. The Guardian, 4th May.

7. Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D. and Bjork, R. (2008) Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 9(3), pp.105-119.

8. Guterl, S. (2013) Is Teaching to a Student’s “Learning Style” a Bogus Idea? Scientific American, 20th September.

9. Newton (2015) The Learning Styles Myth is Thriving in Higher Education. Frontiers in Psychology, Volume 6 (December 2015).

Further Viewing

Recent Posts

- Blackboard Upgrade – March 2026

- Blackboard Upgrade – February 2026

- Blackboard Upgrade – January 2026

- Spotlight on Excellence: Bringing AI Conversations into Management Learning

- Blackboard Upgrade – December 2025

- Preparing for your Physiotherapy Apprenticeship Programme (PREP-PAP) by Fiona Barrett and Anna Smith

- Blackboard Upgrade – November 2025

- Fix Your Content Day 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – October 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – September 2025

Tags

ABL Practitioner Stories Academic Skills Accessibility Active Blended Learning (ABL) ADE AI Artificial Intelligence Assessment Design Assessment Tools Blackboard Blackboard Learn Blackboard Upgrade Blended Learning Blogs CAIeRO Collaborate Collaboration Distance Learning Feedback FHES Flipped Learning iNorthampton iPad Kaltura Learner Experience MALT Mobile Newsletter NILE NILE Ultra Outside the box Panopto Presentations Quality Reflection SHED Submitting and Grading Electronically (SaGE) Turnitin Ultra Ultra Upgrade Update Updates Video Waterside XerteArchives

Site Admin