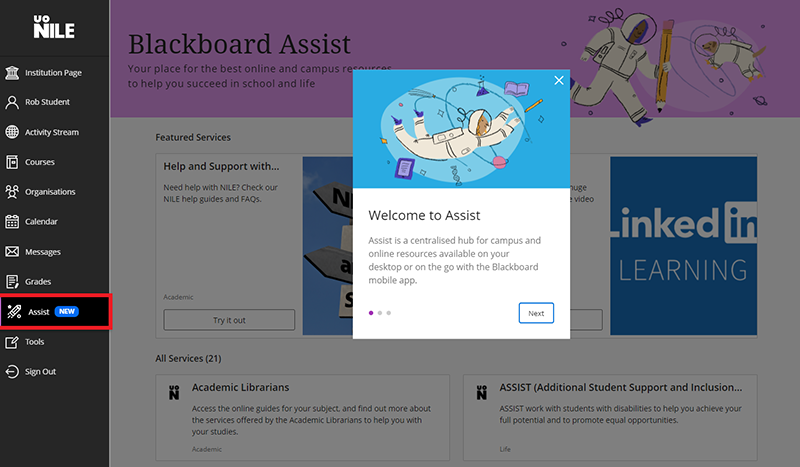

New to NILE this week is Blackboard Assist, a curated collection of links to useful services, information, help and resources available to University of Northampton students.

To see what’s available, simply click on the ‘Assist’ link in the NILE main menu.

From the 6th of November 2020 onwards, staff and students will notice that the Blackboard Content Editor looks a little different.

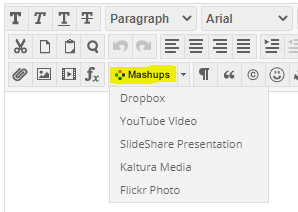

Where previously you’ll have seen and used this version of the content editor:

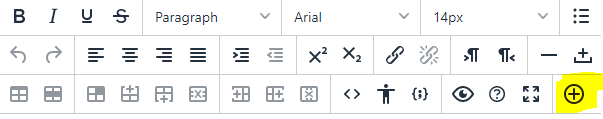

You’ll now see and use this updated and improved content editor:

An important difference between the old and new content editors is the ‘Mashups’ button. In the old content editor it looked like this:

While in the new one it is now a ‘plus’ button:

There are lots of great reasons to like the updated content editor. Adding content has been simplified, and it works better on both hand-held devices and larger screens. There are several improvements for accessibility and some new features, too. Here are six enhancements you can look forward to:

1. The Power of Plus. One easy menu for adding content from your computer, cloud storage, Content Collection, or integrated tool. The content editor will automatically recognize the kinds of files you add.

2. Better for All Devices. The editor is better suited for all devices—small screen or big. It’s easier to author on mobile devices because pop-ups are gone.

3. Improved Accessibility. The editor is more accessible due to higher contrast icons and menus, and the removal of pop-ups improves the experience for screen reader users. A new accessibility checker helps authors make content more accessible while they’re creating content. An Ally licence isn’t required for the accessibility checker; it also complements Ally capabilities because it helps users while they’re initially authoring.

4. Better Copy and Paste. Pasting content from Word, Excel, and websites is even better. Easily remove extra HTML but retain basic formatting.

5. Simple Embed. When pasting links to websites such as YouTube, Vimeo, and Dailymotion, the videos are automatically embedded for inline playback—there’s no need to fuss with HTML. Other sites including The New York Times, WordPress, SlideShare and Facebook will embed summary previews.

6. Display Computer Code. Authors can now share formatted computer code snippets, super handy for computer science classes and coding clubs.

If you have any questions about the new content editor, please feel free to contact your learning technologist.

The core technology underpinning NILE, known as Blackboard Learn, is changing. This will have a major impact across the University as NILE courses are updated to Blackboard Learn Ultra over the next three academic years, starting with Level 4 and Foundation courses for teaching beginning in the 2021/22 academic year.

Blackboard Learn Ultra is a modern, responsive VLE, that has been designed to work across the widest range of devices. While the original version of Blackboard Learn was, and in many respects still is, a highly functional and well-engineered VLE, it does not have the same ability to work seamlessly across the full range of devices that our students now expect. Blackboard Learn Ultra is Blackboard’s answer to the challenges posed by today’s students, the majority of whom now access the VLE from a mobile device.

The Ultra experience is very different to the Original experience. From a design point of view it has a simpler, more modern and less cluttered look-and-feel. And because it has been designed with mobile devices in mind, it flows and responds well on smaller screens, whilst giving users a similar experience regardless of whether it is accessed on a desktop, laptop, tablet, or smartphone.

We have titled the project to move NILE from Blackboard Learn Original to Blackboard Learn Ultra ‘UON Ultra’, and you can find out more about the project and the timescales here:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-guides/blackboard-ultra

As well as having a NILE course for each of your modules, your programme has its own NILE course too. For the 20/21 academic year we have been working with colleagues in IT Services to make improvements to the way that programme courses are created in NILE, which will make the process of finding and using programme courses much easier.

During the 19/20 academic year, 3,410 programme courses were created in NILE. Of these, only 6% were actually used, and the story is the same in previous academic years. The reason for this very low take up of programme courses is actually due to the way that NILE automatically creates a large number of programme course variations based around year and mode of study. For example, when trying to find the 19/20 programme course for History, you’ll be faced with the following list:

- CBAAHISTY-1920: 19/20 BA History

- CBAAHISTY-1FT-1920: 19/20 BA History Stage 1 FT

- CBAAHISTY-1PT-1920: 19/20 BA History Stage 1 PT

- CBAAHISTY-2FT-1920: 19/20 BA History Stage 2 FT

- CBAAHISTY-2PT-1920: 19/20 BA History Stage 2 PT

- CBAAHISTY-3FT-1920: 19/20 BA History Stage 3 FT

- CBAAHISTY-3PT-1920: 19/20 BA History Stage 3 PT

- SUBHIST-1920: 19/20 History

The end result here is that it is often difficult to know which of these programme courses is the best one to use. Additionally, the most requested type of programme course (i.e., the one with all of your students on it) is not actually in the above list because it is not automatically created; rather it has to be generated manually by merging multiple programme courses together.

The good news is that earlier in the year, SEC (Student Experience Committee) approved a proposal to improve and simplify the creation of programme courses in NILE, the result being that your programme now has only one NILE course, and all of your students are automatically enrolled on it.

To return to the above example, there is now only one programme course in NILE for History this academic year.

- CBAAHISTY-2021: 20/21 BA History

This course contains all single and joint honours students; first, second and third year students; full-time and part-time students: in fact, anybody and everybody studying History at UON during the 20/21 academic year.

But this doesn’t mean that programme courses now have to be one-size-fits-all affairs. While you can use the new programme courses to communicate easily with and create activities and resources for all your students at once, you can also use the groups and adaptive/conditional release tools in Blackboard to communicate with and create activities and resources for specific groups of students.

More information

If you have any questions about finding and using your programme course, or about how to set up groups in your course and release content to or communicate with specific groups of students, please do get in touch with your learning technologist.

What is UON Ultra?

UON Ultra is a five-year project to migrate the University’s Virtual Learning Environment (VLE), NILE, from Blackboard Learn Original (hereafter Original) to Blackboard Learn Ultra (hereafter Ultra). The purpose of moving from Original to Ultra is to ensure that the University is using a modern VLE that is intuitive, mobile friendly, device agnostic, responsive, and accessible: i.e., a VLE that best supports our students and our mode of teaching, and which works equally well regardless of whether it is accessed via a desktop, laptop, iPad, etc., or smartphone.

Who will the project impact?

Original is the University’s digital campus and has been used at Northampton since 2002. Original is embedded in all aspects of teaching and learning at the University: it is where online teaching and learning takes place; where online learning activities are engaged in; where teaching and learning materials are made available to students; and, since 2012, is where almost all students’ assignments are submitted, and where students receive their assignment grades and feedback. The project will therefore impact all University students and all academic staff at the University and at partner institutions.

Who are the project delivery team?

UON Ultra will be delivered by the Learning Technology Team, in conjunction with academic staff from across the faculties.

What are the key dates and milestones for the project?

UON Ultra will be delivered in five phases over five academic years, starting in late-2019 and ending in summer 2024. The delivery timescale has been chosen and approved by UMT to ensure minimal impact to students who are used to Original, and to allow staff as much time as possible to get used to working with Ultra.

Phase one – 2019/20

• October to December 2019: Blackboard Original Managed Hosting (MH) to Software as a Service (SaaS) migration planning and testing.

• December 2019: Migrate all Original environments (Production, Staging, Test) from MH to SaaS.

• January 2020: Upgrade Original to Ultra Base Navigation (UBN) on Test.

• February 2020: Design and deliver pilot course EDUM129 via Ultra on Test.

• May 2020: Upgrade Original to UBN on Staging.

• June 2020: Upgrade Original UBN on Production.

• June to September 2020: Recruit participants to Ultra pilot project and design modules (approx. 10) for Ultra delivery from September 2020.

Phase two – 2020/21

• September 2020: First teaching of pilot Ultra modules.

• September 2020: Creation of test Ultra courses for all Level 4 modules.

• From September 2020: Ultra training for academic staff. Subject areas to receive bespoke training from their learning technologist.

• September 2020 to August 2021: Design of level 4 Ultra courses by academic staff (with support from the Learning Technology Team).

Phase three – 2021/22

• September 2021: First teaching of all Level 4 modules via Ultra.

• September 2021: Creation of test Ultra courses for all Level 5 modules.

• From September 2021: Continuation of Ultra training for academic staff. Subject areas to receive bespoke training from their learning technologist.

• September 2021 to August 2022: Design of level 5 Ultra courses by academic staff (with support from the Learning Technology Team).

Phase four – 2022/23

• September 2022: First teaching of all Level 5 modules via Ultra.

• September 2022: Creation of test Ultra courses for all Level 6/7/8 modules.

• September 2022 to August 2023: Continuation of Ultra training for academic staff. Subject areas to receive bespoke training from their learning technologist.

• September 2022 to August 2023: Design of level 6/7/8 Ultra courses by academic staff (with support from the Learning Technology Team).

Phase five – 2023/24

• September 2023: First teaching of all Level 6, 7 and 8 modules via Ultra.

• September 2023: First use of Ultra programme-level courses.

Where can I find out more about Ultra?

The Learning Technology Team will, of course, provide plenty of bespoke training on Ultra from September 2020 onwards, but Blackboard have also created training and support materials about Ultra which you can access.

Blackboard’s LearnUltra site contains a lot of information about Ultra and explains the benefits of using it: https://learnultra.blackboard.com/

Blackboard Ultra Training Videos: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLontYaReEU1tCbsCDP-u_wsKdkDBegIhH

Any questions?

If you have any questions about the UON Ultra project, please contact the Head of Learning Technology, Rob Howe, at rob.howe@northampton.ac.uk

New Box View to Bb Annotate

At the end of June, staff will notice a change in the way that they annotate students’ essays and reports in the Blackboard Assignment tool. Many staff use Turnitin to mark essays and reports, etc., and this update does not affect Turnitin at all; however, staff using the Blackboard Assignment tool will want to familiarise themselves with this update.

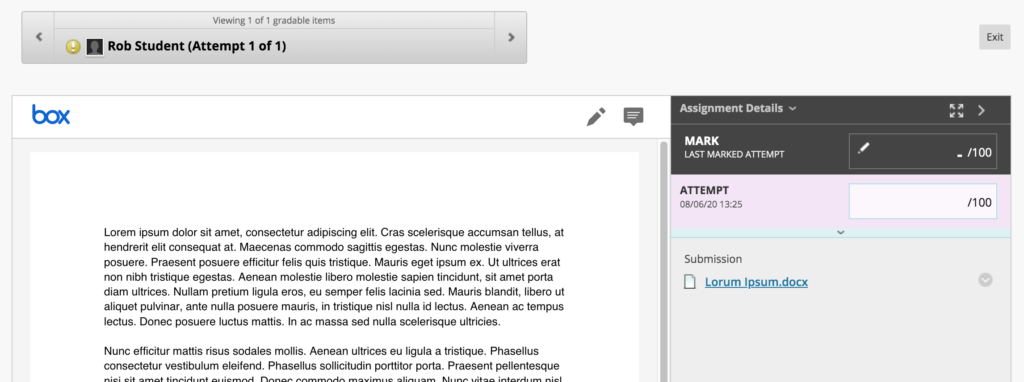

At present, the annotation function in the Blackboard Assignment tool is provided by New Box View, and it looks like this:

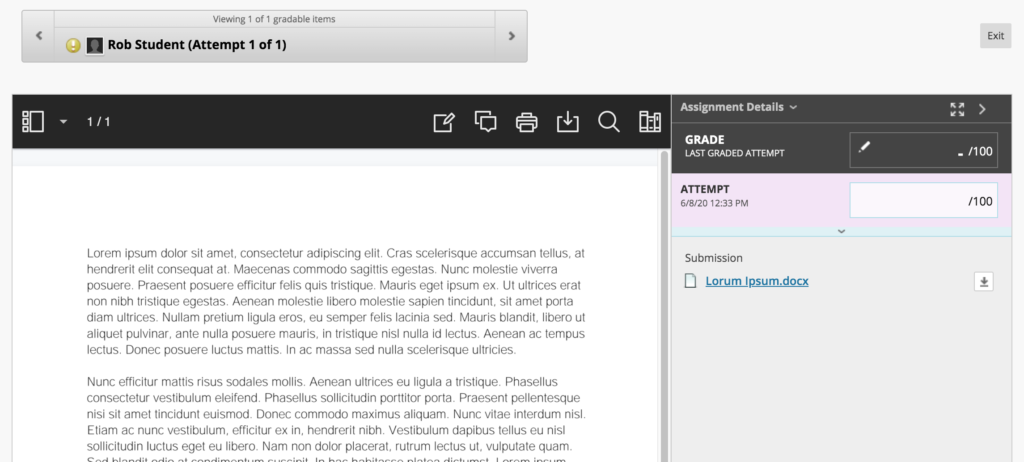

At the end of June, Blackboard are replacing New Box View with Bb Annotate. Following this upgrade you will notice that the tool looks a little different, and you’ll find that the annotation options have been greatly improved:

If you are planning on using the Blackboard Assignment tool to provide feedback and grades to students from July 2020 onwards, please familiarise yourself with the new Bb Annotate tool. Full guidance is available at: https://help.blackboard.com/Learn/Instructor/Assignments/Grade_Assignments/Bb_Annotate

Notes about the migration from New Box View to Bb Annotate

- All pre-existing annotations created through New Box View will be migrated and visible in Bb Annotate.

- When a student or a member of staff accesses an annotated file during the migration, it will take a little bit longer to load but will be displayed in the new Bb Annotate viewer.

- If a member of staff is actively annotating a file using New Box View during the migration, the file will not migrate to Bb Annotate until the member of staff has completed that session. Upon loading the submission file again, it will display in the Bb Annotate viewer.

- Members of staff will be able to delete annotations as well as add new comments to any existing comment created using New Box View.

Supported file types in Bb Annotate

You can view and annotate these document types directly in the browser with Bb Annotate:

- Microsoft Word (DOC, DOCX)

- Microsoft PowerPoint (PPT, PPTX)

- Microsoft Excel (XLS, XLSM, XLSX)

- OpenOffice Documents (ODS, ODT, ODP)

- Digital Images (JPEG, JPG, PNG, TIF, TIFF, TGA, BMP)

- Medical Images (DICOM, DICM, DCM)

- PSD

- RTF

- TXT

- WPD

Help and support with Bb Annotate

Full guidance on using Bb Annotate is available at: https://help.blackboard.com/Learn/Instructor/Assignments/Grade_Assignments/Bb_Annotate

Staff can also get help and support with Bb Annotate from their learning technologist:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-help/who-is-my-learning-technologist

New look-and-feel for the NILE homepage

June 2020 sees a new look-and-feel for the NILE homepage. While the new homepage is indeed radically different, NILE courses are entirely unaffected. You can read more about the new NILE homepage here:

What is the new NILE homepage for staff

https://askus.northampton.ac.uk/Learntech/faq/230369

What is the new NILE homepage for students

https://askus.northampton.ac.uk/Learntech/faq/230368

New NILE courses for the 20/21 academic year

New NILE courses for the 20/21 academic year will be available for use from the 2nd of June onwards. As usual, the new courses follow the standard template as set out in the NILE Design Standards, so you can create your courses afresh, or you can copy materials from your 19/20 courses into your 20/21 courses. To copy materials across, please follow very carefully our instructions about how to do this:

Bulk copying content between courses in NILE

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-guides/blackboard-learn#s-lg-box-15196768

Full information about finding and setting up your new NILE courses can be found in our FAQ – How do I set up my new NILE course for the upcoming academic year?

https://askus.northampton.ac.uk/Learntech/faq/180655

There are no significant changes to the way that module courses have been created, however, there are major changes to the way that programme courses have been created.

Changes to NILE programme courses

Earlier this year the Student Experience Committee approved changes to the way that programme courses are created in NILE. For many years each programme has had a number of different programme course variations in NILE, which meant that for most programmes there were often eight different variations, and no single course that collected together all students on a programme. From this year onwards there is now a single programme course per programme per academic year, and this course has all students on it who are taking the programme (all years of study, full- and part-time, single and joint honours). This means that a single honours student will be enrolled on one programme course, and a joint honours will be enrolled on both of their programmes courses, plus the joint honours programme course. Foundation students will also have a single programme course for all foundation students.

NILE updates for anonymous marking

As anonymous marking becomes the new normal for the 20/21 academic year, changes in the integration between NILE and the Student Records System mean that you will no longer see students on your NILE courses who have transferred or withdrawn from your modules. The main effect of this is that you can now safely use Turnitin’s ‘Email non-submitters’ tool.

Additionally, and to assist with the process of anonymous marking, the Learning Technology Team have put together the following guides for staff and students:

Anonymous marking guide for staff:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/sage/turnitin_anonymous

Guidance for students submitting work anonymously

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/sage/turnitin-submission/anonymous

Help and support with NILE

As ever, for help and support with any of the NILE tools, or simply to find out more about what NILE is and how the Learning Technology Team can help you, please see our website:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/

And do feel free to contact your learning technologist for advice and guidance about anything related to educational technology in general, or NILE in particular:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-help/who-is-my-learning-technologist

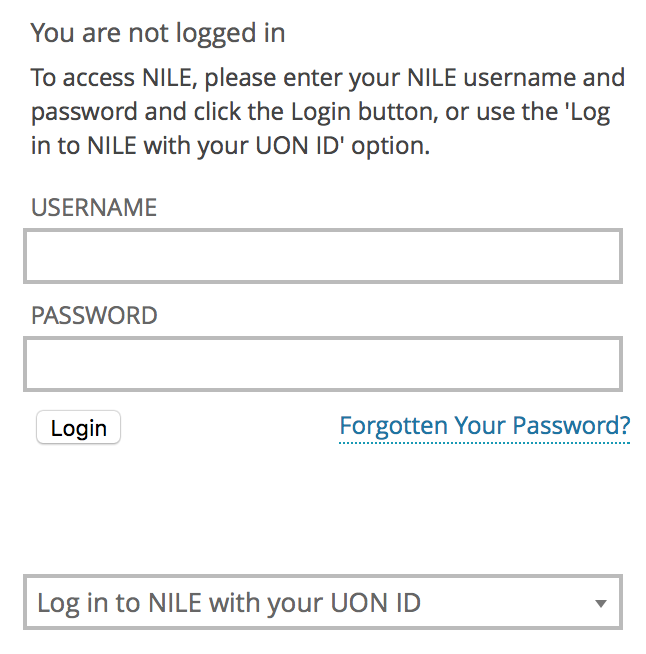

As part of our work improving and updating NILE, we are making some changes to the way that you log in to NILE, with the aim being to make accessing NILE both simpler and more secure.

You will still use your current University of Northampton username* (your student number, or staff ID) and password to login to NILE; these will not change. In fact, most of the changes will be made behind the scenes as we upgrade to the latest and most secure method of authentication, but there are one or two changes that you will notice.

Firstly, once you have logged in to the Student Hub or Staff Intranet** you will no longer have to log in to NILE again. Just click on the NILE link, and you’ll be taken directly into NILE without having to enter your username and password again.

Secondly, if you access NILE directly via nile.northampton.ac.uk, then for a limited time you’ll see that you have two login options. You’ll have the regular username and password option, but you now also have an option to use the new ‘Log in to NILE with your UON ID’ option. If you prefer to access NILE directly, rather than going via the Student Hub or the Staff Intranet, we encourage you to start using the new ‘Log in to NILE with your UON ID’ option.

When you use these new NILE login options, then when you come to log out of NILE you’ll see that you are presented with two choices: you can either log out of NILE only (which logs you out of NILE, but keeps you logged in to other University systems, including the Student Hub, Staff Intranet, and your University Office 365 and OneDrive accounts, etc); or you can securely log out of NILE and all University systems at the same time.

*Your University username will be in one of the following formats:

- Students: this is your 8 digit UON student number;

- University of Northampton Staff: this is your UON staff username, usually comprising your initial(s) and the first few characters of your last name;

- Staff working at partner institutions: this is your ARMS account ID, and is an 8 digit number beginning 999.

**Please note that only University of Northampton staff can log into the Staff Intranet. Partner staff will always need to access NILE by going directly to nile.northampton.ac.uk

If you’ve unexpectedly found yourself in the midst of a terrifying global pandemic and have been told that you will now be delivering all your classes online, then you may find one or two things in this blog post that will help you.

1. Which tool(s) should I use for online teaching?

In the world of online teaching, you will often find people referring to synchronous and asynchronous tools. All this means is real-time, or not. Synchronous tools are real-time online tools, and are those that are used instead of a face-to-face classroom session – they allow people to interact online with one another in real time: think Skype, or Facetime, or just being on the phone with someone. Asynchronous tools are those that are used when people can interact as and when they have time – they do not typically require an instantaneous response: think email, or text messaging, or simply writing letters.

At the University of Northampton, your synchronous teaching and learning tool of choice is Blackboard Collaborate Ultra. It is the University’s virtual classroom tool, and has been part of NILE and enabled and available in your NILE sites for a few years now. If you are moving a face-to-face class online it is highly probable that you will want to use Blackboard Collaborate Ultra (hereafter simply Collaborate). Asynchronous tools are a little more varied, but given the current situation let’s keep it simple and say that unless you have a better idea (which is perfectly possible), Blackboard’s Discussion Board tool is your asynchronous tool of choice.

The University’s Learning Technology Team will support you to understand and use these tools, both from a technical and a pedagogical perspective. However, as you will appreciate, they’re pretty busy at the moment, so here are a few things that may help you out while you’re waiting for a response to that email you just sent them.

What you need to know about Collaborate

Collaborate is already in all of your NILE module site(s) – each and every one of them. You don’t need to do anything to start using it with your students, apart from making the ‘Virtual classroom’ link available (which is covered in the staff Collaborate guide).

There is guidance on using Collaborate for staff and students available here:

Collaborate Guide for Staff

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-guides/blackboard-collaborate

Collaborate Guide for your Students

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/students/nile-guides/blackboard-collaborate

What you need to know about Discussion Boards

Discussion Boards are also already activated and available in your NILE site(s). You may want to use these in between Collaborate sessions in order to facilitate class discussions in the days or weeks in between classes.

If you’d like to know more about Discussion Boards (and Blogs and Journals too), you’ll find this guide useful:

Blogs, Journals and Discussion Boards – A Guide for Staff

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/sage/blog-journal-discussion

2. What happens with assessments online?

For the most part, coursework assessments will be able to continue normally. However, if your students were due to take an in-class test then this is going to be a problem.

A good option here is to consider making your in-class test into an open book or take home exam. It may be the case that with minor modifications your in-class test paper can be revised to work well when students are at home with access to their books and to the Internet. You may also consider giving students a longer window in which to take the exam – if you’ve not thought about using a 24 hour exam before then perhaps this is the time to try it out!

If this appeals, then then the best way to put it into practice is to release your open book/take home exam paper on NILE at the point at which the exam begins, and to setup a Turnitin submission point with a submission due date/time for the end of the exam to collect the papers in at the end (make sure it accepts submissions after the due date though, as some students may be allowed extra time). Most students are familiar with using Turnitin by this point in the year, and Turnitin’s text matching feature will deter collusion and plagiarism.

Full guidance on setting up and using Turnitin is available on our website at:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/sage/turnitin

3. Do I have to teach differently online?

Online teaching is certainly different from face-to-face teaching, but many, if not all, of the principles of good teaching apply regardless of whether you are teaching online or face-to-face.

One of my favourite books about teaching is Ken Bain’s What the Best College Teachers Do (2004). In a study entitled What the Best Online Teachers Should Do, which was conducted a few years after Bain published his book, a group of teachers tried out Bain’s recommendations in the online teaching and learning environment. While they found that online teaching was different to, and, sometimes, more difficult than, face-to-face teaching, the three key principles of ‘good teaching’ applied both in the online and in the face-to-face teaching worlds. In a nutshell, these principles are:

Principle 1. Foster student engagement

“Bain (2004) asserts that the best college teachers foster engagement through effective student interactions with faculty, peers, and content. They see the potential in every student, demonstrate a strong trust in their students, encourage them to be reflective and candid, and foster intrinsic motivation moving students toward learning goals.”

“In the online environment, lecture need not and should not be the primary teaching strategy because it leads to learner isolation and attrition. The most important role of the teacher is to ensure a high level of interaction and participation … student engagement with teachers, peers, and content is vital in the online learning environment.”

Principle 2. Stimulate intellectual development

“According to Bain the best teachers create a natural critical learning environment. … when it comes to stimulating intellectual development in students, questions are the key to creating a natural critical learning environment … Questions are universal; they can be asked and answered anytime or anywhere. They work best when the students ask them or when the students find them interesting. As long as it is possible to ask questions in an online class, then Bain’s natural critical learning environment can exist in an online class.”

Principle 3. Build rapport with students

“One way that Bain identified highly effective teachers was by how they treated their students. He recognized that such teachers ‘tend to reflect a strong trust in students. These teachers usually believe that students want to learn and they assume, until proven otherwise, that they can.'”

” … when it comes to building rapport with students, the best online teachers should understand the characteristics of their students and adapt accordingly … An important element of rapport building is that teachers are flexible – with regard to getting to know their students, getting their students to know them, working around deadlines, and creating an atmosphere that enhances learning.”

And if those three principles sound pretty much like what you’re doing already in your regular face-to-face classes, that’s probably because they are! So maybe online teaching is not too different from face-to-face teaching after all. While the environment is certainly different, the aims and principles of good teaching remain the same.

NB. All the above quotes are from Brinthaupt, T. M., et al., (2011) What the Best Online Teachers Should Do. Merlot Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 7(4). Available from: https://jolt.merlot.org/vol7no4/brinthaupt_1211.htm

4. Where can I get more help and support?

There is more help and support available about all aspects of technology-enabled teaching and learning from the Learning Technology Team.

You can find lots of information about NILE and about the various digital tools available to you and your students on our website:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech

You can take our online, self-study NILE training course:

https://mypad.northampton.ac.uk/niletrainingewo/

If you are a member of staff at the University of Northampton you can also get more help from your learning technologist:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-help/who-is-my-learning-technologist

If you are a member of staff at one of our UK partner or international partner organisations, you can get more help from the NILE champion at your institution:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-help/partners-nile-champions

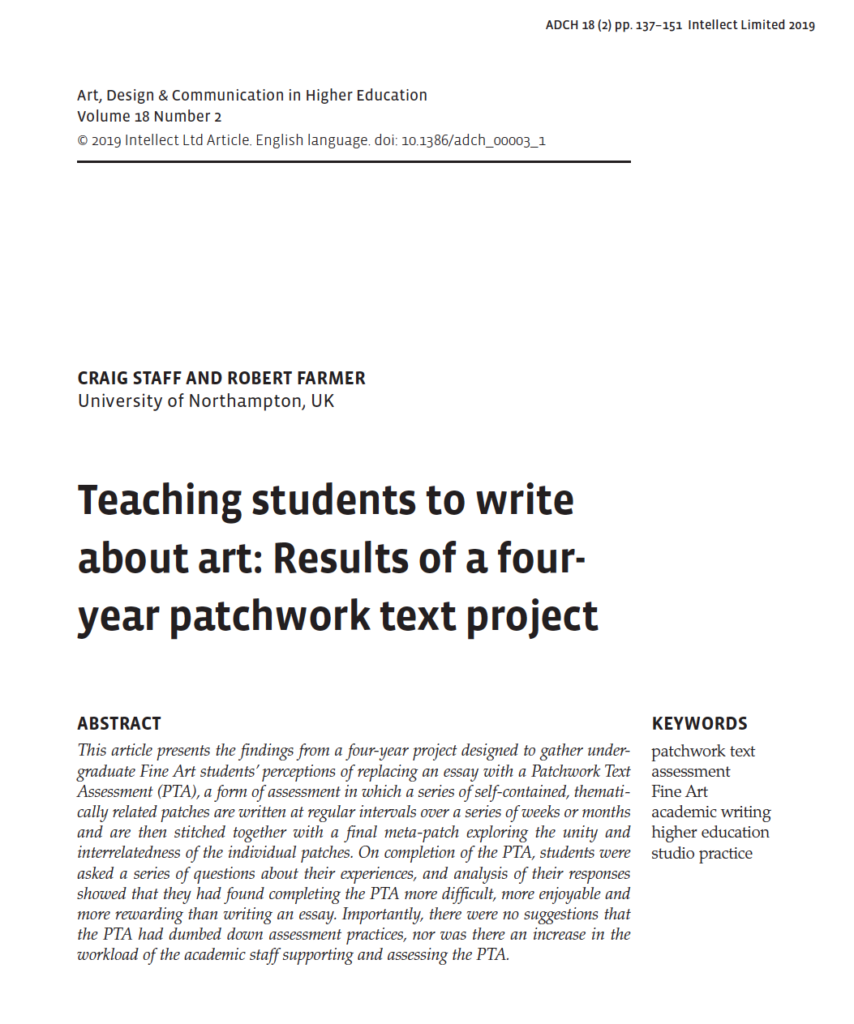

Dr Craig Staff, Reader in Fine Art, and Robert Farmer, Learning Technology Manager, have published an article in the latest edition of Art, Design and Communication in Higher Education, a special edition on the theme of democratizing knowledge in art and design education. According to the journal’s editor, Professor Susan Orr, Dean of Learning/Teaching & Enhancement at University of the Arts London “The authors make a strong argument that the patchwork text approach works well within a creative education context, where experimentation and risk-taking are valued.”

The article itself presents the findings from a four-year project designed to gather undergraduate Fine Art students’ perceptions of replacing an essay with a Patchwork Text Assessment (PTA), a form of assessment in which a series of self-contained, thematically related patches are written at regular intervals over a series of weeks or months and are then stitched together with a final meta-patch exploring the unity and interrelatedness of the individual patches.

On completion of the PTA, students were asked a series of questions about their experiences, and analysis of their responses showed that they had found completing the PTA more difficult, more enjoyable and more rewarding than writing an essay. Importantly, there were no suggestions that the PTA had dumbed down assessment practices, nor was there an increase in the workload of the academic staff supporting and assessing the PTA.

The full article can be viewed and downloaded here: https://doi.org/10.1386/adch_00003_1

Recent Posts

- Blackboard Upgrade – February 2026

- Blackboard Upgrade – January 2026

- Spotlight on Excellence: Bringing AI Conversations into Management Learning

- Blackboard Upgrade – December 2025

- Preparing for your Physiotherapy Apprenticeship Programme (PREP-PAP) by Fiona Barrett and Anna Smith

- Blackboard Upgrade – November 2025

- Fix Your Content Day 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – October 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – September 2025

- The potential student benefits of staying engaged with learning and teaching material

Tags

ABL Practitioner Stories Academic Skills Accessibility Active Blended Learning (ABL) ADE AI Artificial Intelligence Assessment Design Assessment Tools Blackboard Blackboard Learn Blackboard Upgrade Blended Learning Blogs CAIeRO Collaborate Collaboration Distance Learning Feedback FHES Flipped Learning iNorthampton iPad Kaltura Learner Experience MALT Mobile Newsletter NILE NILE Ultra Outside the box Panopto Presentations Quality Reflection SHED Submitting and Grading Electronically (SaGE) Turnitin Ultra Ultra Upgrade Update Updates Video Waterside XerteArchives

Site Admin