If you’re interested in understanding more about some of the new features that Blackboard will be bringing to Ultra and Original courses, you can join Blackboard’s Product Management leaders as they provide an update on the Blackboard Roadmap.

There are two sessions, one on the Ultra roadmap, and one on the Original roadmap. Even if you can’t attend the webinars, if you sign up to attend you will receive a recording of the webinar.

Ultra Course View

Wednesday, November 3, 2021. Time: 1:00pm GMT

Original Course View

Wednesday, November 3, 2021. Time: 12:00pm GMT

To find our more, and to sign-up, go to: https://go.blackboard.com/RoadmapWebinarSeries

Between November 2021 and June 2022, Blackboard are offering a series of seven free webinars to understand how Blackboard Learn Original and Learn Ultra can support your teaching, your subject and your students’ learning.

You can sign up for one, some, or all the webinars. Even if you can’t make the live webinars, by signing up you will receive the recordings of the sessions that you signed up to.

The full series of webinars is as follows:

- How do you to create and effectively use discussion forums in Learn Original and in Learn Ultra?

Thursday, November 4 at 10:00am GMT

>>View Recording - How do you create and upload content in Learn Original and in Learn Ultra?

Thursday, December 2 at 10:00am GMT

>>View Recording - How does Adaptive Release work in Original and Conditional Availability in Ultra?

Thursday, February 10 at 10:00am GMT

>>View Recording - How do you design and manage assessment items in Learn Original and in Learn Ultra?

Thursday, March 10 at 10:00am GMT

>>View Recording - How do you create a marking structure and provide feedback using rubrics, audio and video in Learn Original and in Learn Ultra?

Thursday, April 7 at 11:00am BST

>>View Recording - How do you use the Grade Centre in Learn Original and the Gradebook in Learn Ultra?

Thursday, May 12 at 11:00am BST

>>View Recording - How to use data and key tools to monitor and support student progress and personalised learning in Learn Original and in Learn Ultra?

Thursday, June 9 11:00am BST

>>View Recording

Find out more, and sign up to attend here:

https://go.blackboard.com/lecturer-series

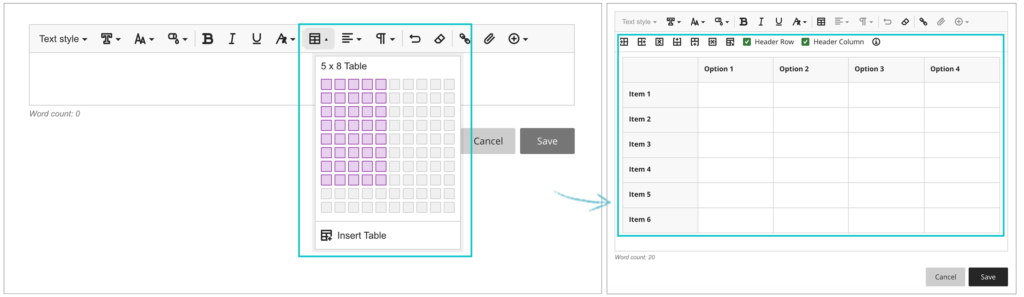

From October 8th 2021, one of the most requested features of Blackboard Ultra will finally be available: the ability to create tables in the Ultra RTE (Rich Text Editor).

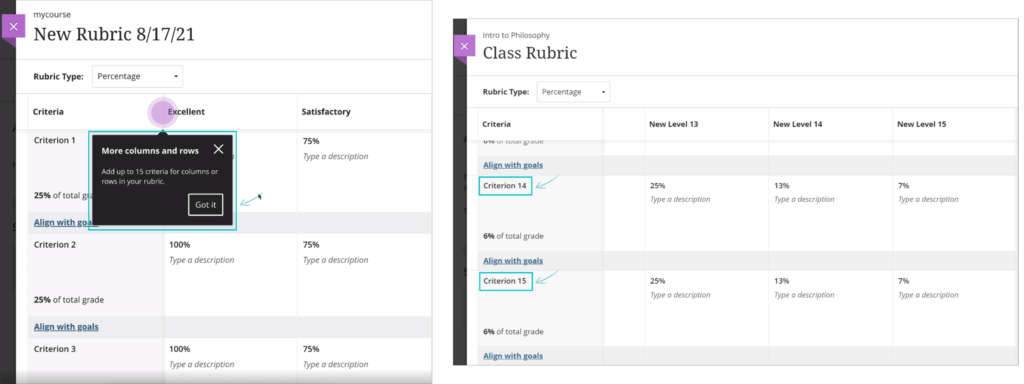

Also included in the upgrade, from the 8th of October onwards the maximum number of columns and rows in Blackboard Ultra rubrics will increase from ten to fifteen.

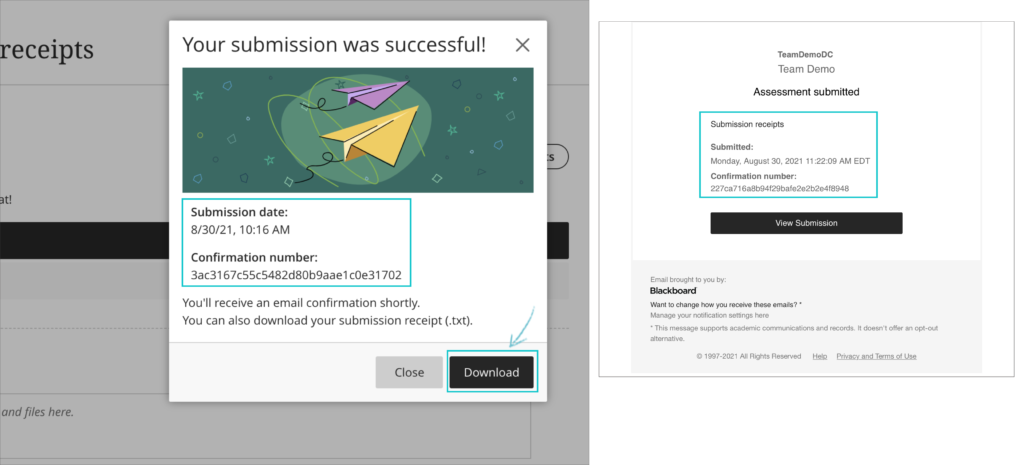

And when students submit Blackboard Ultra assignments, from the 8th of October they will receive confirmation via email and downloadable receipt that their submission has been successful. Please note that this does not apply to Turnitin assignments in Blackboard Ultra courses. Students will still be able to download their submission receipts for Turnitin assignments in Ultra courses, but will not be emailed submission receipts. Emailed submission receipts will only be available for Blackboard assignments in Ultra courses from 8th October onwards.

Also included in the upgrade are various other minor big fixes, etc.

August 6th 2021 will bring some important changes to Blackboard Ultra courses.

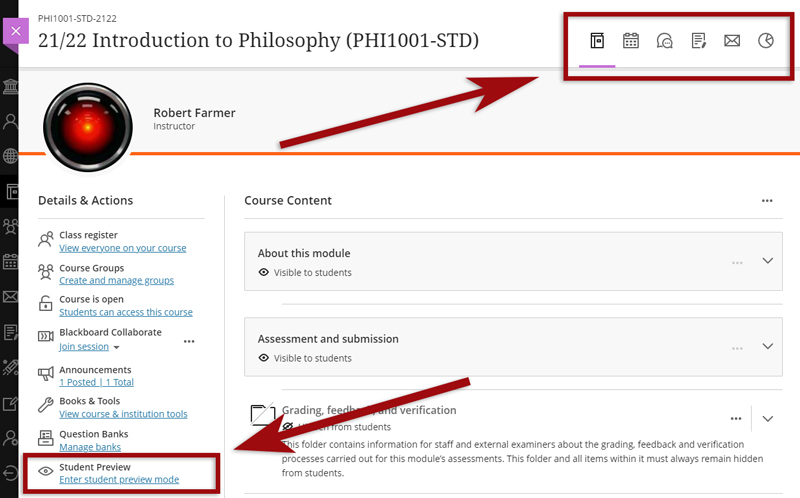

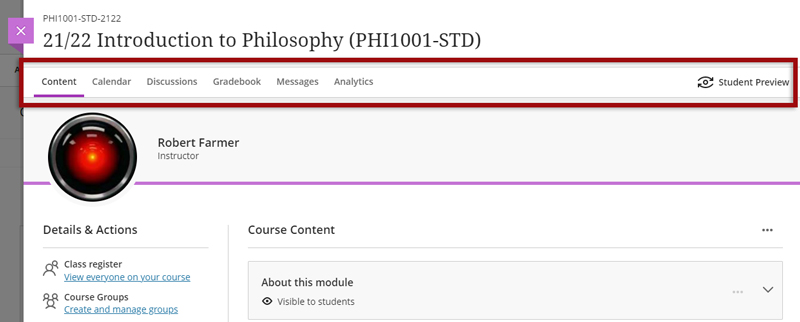

First, and most difficult to miss, is a change to the location of the Tools menu and the Student Preview button. Currently the Tools menu is on the upper right hand side of the page and is indicated by icons. This will move to the left side of the page and will become text buttons instead of icons. The Student Preview button will move from the lower left to the upper right side of the page.

Currently the Tools menu and Student Preview buttons are located as follows:

However, from 6th August onwards they can be found here:

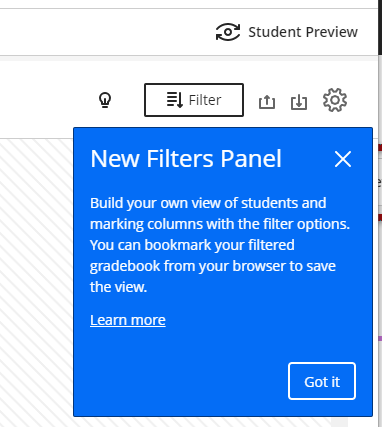

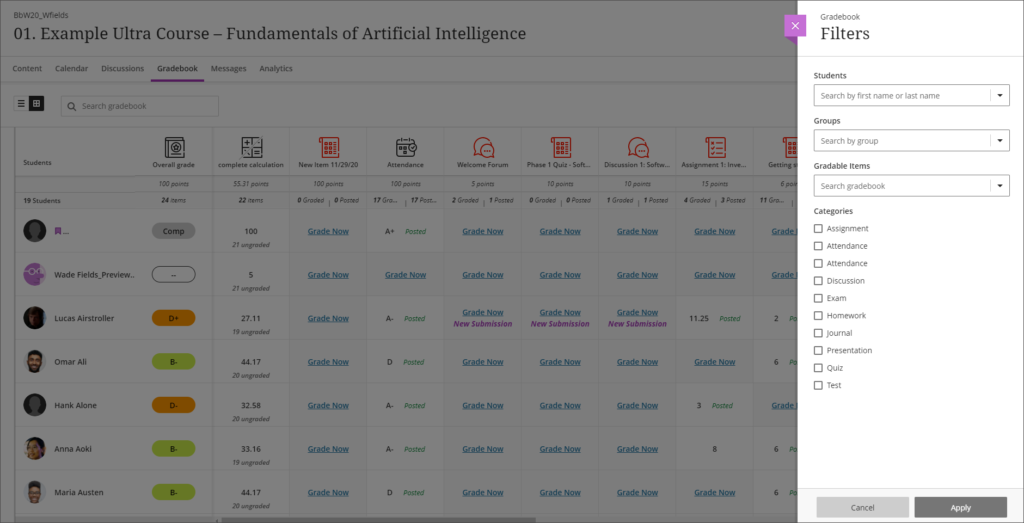

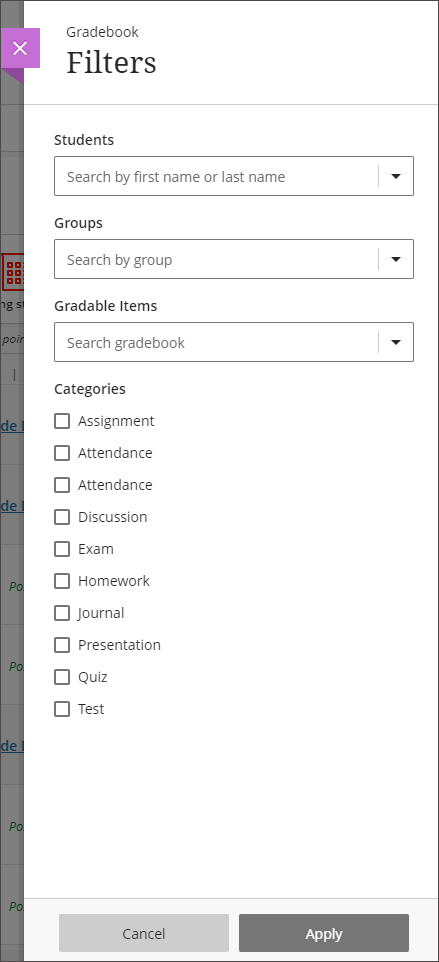

Also coming in the August upgrade is Gradebook filtering. This feature is very much like the Smart Views in Original courses, but also allows quick and easy instant filtering, as well as giving staff the ability to save preferred filters.

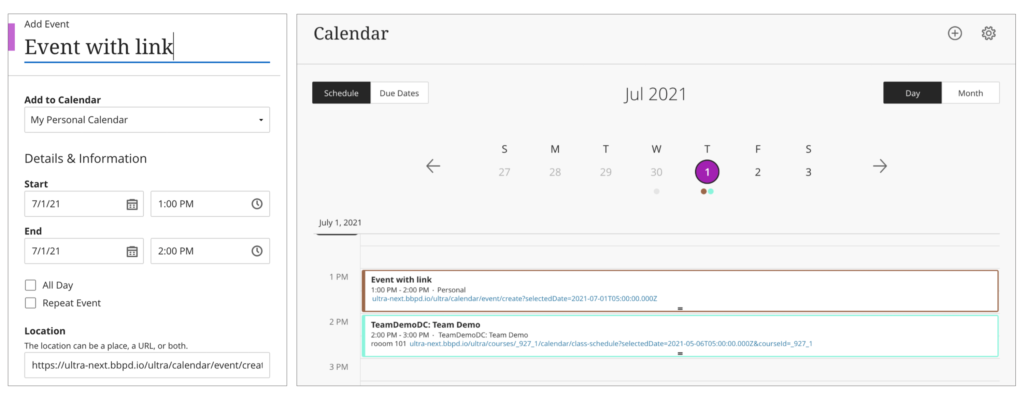

The August upgrade will bring improvements to the Calendar and to the Peer Review tool in Ultra courses. After the upgrade, hyperlinks will be supported in the calendar location field so that staff can link any virtual tool of their choice in the calendar event, and students can launch the virtual session from the calendar itself.

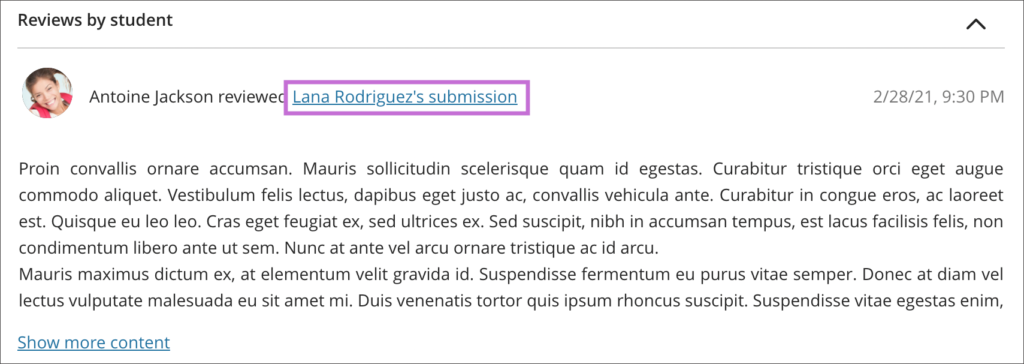

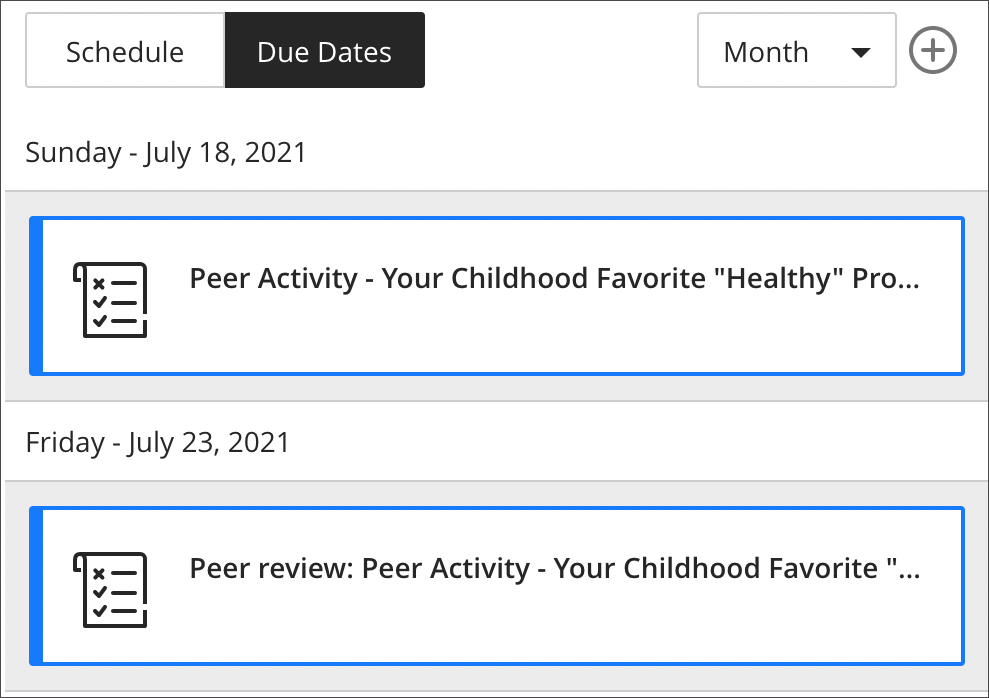

Peer Review was introduced to Ultra courses some time ago, but the August upgrade brings some useful improvements. The current capabilities of the Peer Review tool are explained in Blackboard’s guide, Peer Review for Qualitative Peer Assessments. Following the August upgrade staff will be able to access the submissions reviewed by a student right from that student’s grading panel. Students will also have direct access to the submissions available for their review from either the Due Date or the Calendar views. This makes it easier for them to act when reviewing their pending tasks.

NILE courses for the 2021/2022 academic year are now available.

Courses will be Original or Ultra depending on type of course and level of study. Module-level courses at Foundation and Level 4 will be Ultra. Module-level courses at Levels 5, 6, 7, and 8 will be Original. All programme-level courses will be Original. You can find out more about the transition from Original to Ultra on our Blackboard Learn Ultra guides:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-guides/blackboard-ultra

Find and enrol on your new NILE courses using the process outlined in our FAQ, ‘How do I enrol/remove myself off a module site?

https://askus.northampton.ac.uk/Learntech/faq/181746

The NILE design standards for the 2021/22 academic year were approved at the Student Support Forum meeting on the 15th of April 2021, and have now been published.

The most significant change to NILE design standards for 2021/22 is the inclusion of the design standards for Ultra courses (see, ‘Section B, Tables 5.1, 5.2 and 5.3’).

The design standards for Original courses remain largely unchanged. The only changes of note from the previous year’s standards are:

- Clarification that, should staff wish to, it is fine to update the course landing page from ‘About this module’ to ‘Announcements’ after the first few weeks of teaching (see, ‘Section C, Table 6, About this module [Entry Point*]’.

- Renaming ‘Virtual classroom’ to ‘Blackboard Collaborate’ and having this area available by default (see, ‘Section C, Table 6, Blackboard Collaborate’).

- Removal of the ABL definition from the landing page on programme-level courses (see, ‘Section C, Table 7, My Programme [Entry Point’].

The NILE design standards for 2021/22 are available to view at:

https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-design/nile-design-standards

Introduction

Following up on our recent post, ‘What do UON staff think about Blackboard Ultra?‘, staff who have designed, built and taught students on Ultra courses shared their thoughts with us about the work involved in creating Ultra courses.

In order to better understand this issue, we asked UON staff piloting Ultra courses the following question:

“If you were discussing Ultra with a colleague, what would you advise them on the following two matters:

- How much time would you suggest they put aside for training and getting up-to-speed with Ultra?

- How much time would you suggest they put aside to put their first Ultra course together, assuming that they had already got the static content items (PPTs, PDFs, videos, etc.) they needed already prepared?”

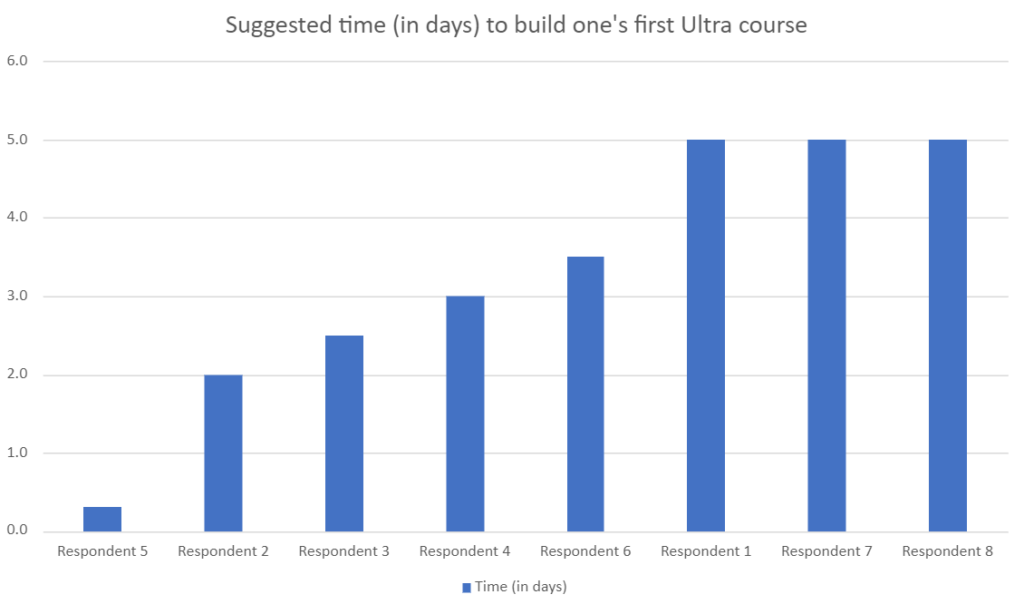

This question was put to all members of staff piloting Ultra courses, and eight responses were received (FAST=4; FBL=1; FHES=3). Of the eight members of staff who responded: one was teaching a 20 credit level 4 module; one was teaching a 20 credit level 4 module and a 10 credit level 5 module; one was teaching a 20 credit level 5 module; two were teaching 20 credit level 6 modules; one was teaching a 40 credit level 6 module; and two were teaching 30 credit level 7 modules.

Findings

The responses to the first question varied, with suggestions ranging from 2 to 3 hours, to 4 to 5 hours, and up to 2 days.

As can be seen from the chart below, the responses to the second question varied very widely; however, both the median and mean averages are very close at 3.25 and 3.29 days respectively. Interestingly, there was no correlation between the credit value of the module and amount of time taken to put together one’s first Ultra course. Respondents 1, 5, 7 and 8 (who chose the most and the least amounts of time) were all teaching 20 credit undergraduate modules.

Please note that the qualitative responses from staff are in many cases considerably more nuanced than the simple quantitative figures presented here in the findings, and in some cases a judgement has been made as to the best single figure to represent a respondent’s views

Recommendations

Given the available evidence, it is suggested that staff may need to spend the following amount of time training, planning, and putting together their Ultra courses.

- Approximately 1 day Ultra training (including Ultra training with a learning technologist, and spending time on one one’s own getting used to Ultra)

- Between 3 and 3.5 days to plan out and put together the first Ultra course

- Between 2 and 2.5 days to plan out and put together subsequent Ultra courses

The following timescales do not take account of the amount of time it takes to prepare, create and update teaching materials and other static content (e.g., PowerPoints, videos, etc.)

Further considerations

Where staff are transferring extant Original courses to Ultra rather than working on a brand new module, this may be a good opportunity to consider a redesign of the NILE site. Some staff have reported that the Original to Ultra process presented a good opportunity to do this. Additionally, these staff also reported that incorporating a redesign made the task of rebuilding their Original courses in Ultra a more worthwhile experience, and that subsequently their Ultra courses were better than their Original courses. Support for a NILE site redesign is available from your learning technologist: https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-help/who-is-my-learning-technologist

From the 1st of March 2021, Kaltura will be making a change to the way that your video files are stored. However, please be aware that this change will not affect the playback of your videos.

When you upload a video file to Kaltura, the original video file that you upload (known as the source file) is automatically converted by Kaltura into a variety of different video formats which are more suited to web streaming. These converted video files (known as transcoded flavours) are the ones that people see when they play back your video. Once your original video file (the source file) has been automatically converted into the various transcoded flavours, it remains on Kaltura, but is not used for video playback.

From the 1st of March 2021, your source video files will be automatically removed from Kaltura after one year. However, all transcoded flavours will be retained, therefore playback of your Kaltura videos will be unaffected.

Please note that once the one-year period has expired and your source video file has been removed, it will no longer be possible to edit your Kaltura video.

Because it won’t be possible to automatically convert Original courses to Ultra, Ultra development courses will be created for all modules at least six months before they are required for first teaching.

Foundation and Level 4 Ultra courses for first teaching in September 2021 are available now.

To enrol on the Ultra development course for your module, please use the Enrol as a Tutor on your Modules tool in NILE.

The ID and name of your module will be in the format: Course ID = ABC1234_ULTRA, Course Name = ABC1234 Ultra Development Course.

Please note that these Ultra development courses are not the final versions of the courses that you will be using for teaching. The actual courses that your students will be enrolled on and which are synchronised with the Student Records System will be created later in the year (usually late May, early June). These Ultra development courses are intended for staff who would like to spend time slowly building their courses over many months, rather than waiting until June to begin the process. If you build your module using an Ultra development course you will need to copy it across later in the year into the course that your students are enrolled on; however, this is a quick and easy process. Our suggestion is that these Ultra development courses are best used as a place to structure, develop and build your module content and activities. Once this is complete, you can add assessment submission points, etc., into the final version of your course later in the year.

Introduction

During the autumn 20/21 term, nine members of academic staff across all three University faculties taught 305 students on twelve Blackboard Learn Ultra modules (FAST=7; FBL=1; FHES=4). During December 2020 and January 2021, these academics shared their thoughts about Ultra with us, and this blog post presents a summary of the main findings from UON staff who have piloted Ultra with their students.

N.B. For clarification, throughout this post ‘Ultra’ refers to the new Blackboard Learn Ultra courses, whereas ‘Original’ refers to the original Blackboard Learn courses (i.e., Blackboard Learn version 9.1 courses) that UON staff have been using for many years.

Main findings

1. Once they had taken the time to get used to Ultra, the majority of staff were generally positive about it, and particularly liked its more modern look-and-feel, referring to it as being simple, clean, smart, slick, bright, and neat. However, for a very small number of staff this simpler, cleaner appearance and the lack of course customisation options was found to be bland and visually uninspiring.

2. In most cases staff noted that it did take quite some time to become familiar and comfortable with the new Ultra interface, and that a reasonable amount of thinking, experimenting and planning time was necessary to work out how to use Ultra and get the best from it.

3. As well as the time taken to get used to Ultra, and to consider how to design their Ultra courses, most members of staff reported the need to spend more time than usual putting their Ultra courses together; i.e., uploading content, and creating online activities, etc. Some staff members found this process too slow, but even those who found the process daunting also noted that it was also a good opportunity to re-evaluate their courses. As this was their first time putting an Ultra course together, most staff members reported some frustrations getting used to Ultra, or with the limitations of Ultra, but for the most part there was the sense that once they had become used to Ultra, it was not difficult to work with.

4. Many members of staff noted a loss of minor functionality with Ultra when comparing it with Original. However, with the exception of a limitation with the journal tool (which has subsequently been updated by Blackboard) the missing functionality usually refers to relatively minor issues (such as the inability to create tables in the text editor, some clumsiness with the messaging tool, difficulty using drag-and-drop function to move content around within the course, or the lack of ability to copy content within a course) which are likely to be remedied in future upgrades. In some cases, the missing functionality reported was actually there, but was difficult to find. Regarding positive comments about Ultra functionality, the Ultra discussion boards were noted as a particularly good tool. Overall, while there were concerns about Ultra’s functionality, there were no comments suggesting that Ultra was unfit for purpose, or unusable/unsuitable for teaching and learning.

5. Not all staff piloting Ultra had assessed student work in their Ultra course at the time they gave feedback, but those who had had mixed comments about the process: some had found it straightforward and intuitive, but others had found difficult and cumbersome.

6. Staff noted no problems with their students using Ultra, and no negative comments from students about Ultra – generally the sense was that students were okay with it, had adjusted to it, and were just getting on with it. One member of staff noted positive comments from their students about Ultra being easier to navigate that Original, better to look at, and displaying well on a mobile device.

7. While most staff were positive (and often very positive) about Ultra, there were a few comments which indicated that some staff were concerned about it not being as functional as Original, and their impression was that while it was a good tool, and one that they would happy use in the future, it was not quite ready yet. However, other staff, even where they noted less functionality with Ultra, did not find this to be especially problematic. Overall, almost all respondents seemed happy with the idea of using Ultra for teaching and learning either immediately, or after a little more development.

8. In terms of rolling out Ultra across all courses at the University, while some staff liked the idea of doing it all at once for all modules, most considered a three-year phased roll-out to be the most prudent and most reasonable option for both staff and students. Nevertheless, quite a number of staff piloting Ultra noted that it was going to be a lot of work for all staff to make the transition to Ultra, especially for those staff who are module leaders and who would be rebuilding their Original courses in Ultra.

Summary

The findings strongly suggest that the University made the correct decision in continuing to use Blackboard as its VLE provider and was right to begin the process of adopting Blackboard Ultra courses. The findings did not suggest any reason to abandon the UON Ultra adoption project or to stick with Original courses for the foreseeable future.

Overall, the findings showed a very good level of support for Ultra, and, for the most part, a preference for Ultra over Original. The main concerns with Ultra were about: i) the time it would take for staff to get used to working with Ultra; ii) the time it would take to rebuild Original courses in Ultra, and; iii) that currently Ultra does not completely match the functionality of Original.

Next steps and future developments

• The University Management Team (UMT) originally stated the University’s commitment to Ultra at a meeting on the 5th of May, 2020, and to a three-year phased roll-out of Ultra courses across the University beginning in September 2021. At a meeting on the 26th of January, 2021, UMT confirmed its ongoing commitment to Ultra and to the Ultra adoption timescales. You can view the Ultra course adoption plan here: https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-guides/blackboard-ultra-faqs#s-lg-box-15342243

• In order to assist staff, and hopefully to reduce the amount of time it takes staff to transition their modules from Original to Ultra, the Learning Technology Team have designed and built two complete Ultra courses as examples of what Ultra courses could look like. Both courses contain the same content, but one is set out thematically, and the other on a week-by-week structure. You can access these courses as explained here: https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-guides/blackboard-ultra-faqs#s-lg-box-15341315

• The functionality of Ultra is improving all the time, and we have shared the Ultra findings from UON staff with Blackboard, who are now using it to help shape future developments of Ultra. You can find out more about the latest developments with Ultra here: https://www.blackboard.com/learnultra/whats-new-learn-ultra

Find out more

You can find out more about the University of Northampton’s move to Blackboard Learn Ultra at: https://libguides.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/staff/nile-guides/blackboard-ultra

Recent Posts

- Blackboard Upgrade – February 2026

- Blackboard Upgrade – January 2026

- Spotlight on Excellence: Bringing AI Conversations into Management Learning

- Blackboard Upgrade – December 2025

- Preparing for your Physiotherapy Apprenticeship Programme (PREP-PAP) by Fiona Barrett and Anna Smith

- Blackboard Upgrade – November 2025

- Fix Your Content Day 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – October 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – September 2025

- The potential student benefits of staying engaged with learning and teaching material

Tags

ABL Practitioner Stories Academic Skills Accessibility Active Blended Learning (ABL) ADE AI Artificial Intelligence Assessment Design Assessment Tools Blackboard Blackboard Learn Blackboard Upgrade Blended Learning Blogs CAIeRO Collaborate Collaboration Distance Learning Feedback FHES Flipped Learning iNorthampton iPad Kaltura Learner Experience MALT Mobile Newsletter NILE NILE Ultra Outside the box Panopto Presentations Quality Reflection SHED Submitting and Grading Electronically (SaGE) Turnitin Ultra Ultra Upgrade Update Updates Video Waterside XerteArchives

Site Admin