One of the more discussed topics at the University of Northampton at present is the idea of the ‘flipped classroom’ or of students engaging in ‘flipped learning’. A major reason why this is being discussed now is that use of the flipped classroom could well be a major feature of the University’s new Waterside campus1, however this is not the only (nor even the best) reason for interest in this subject. As will undoubtedly be clear, the best reason for adopting a flipped learning approach to teaching and learning is that it offers pedagogical advantages, and we will certainly look at some of the evidence in favour of flipped learning in a later blog post. However, our purpose in this post is simply to outline what flipped learning is, and how one might go about doing it.

The key points in this post are:

1. Very simply put, the flipped classroom is one where students access content and engage in activities designed to develop their understanding before class, and then use the class time to discuss and engage in depth with issues, ideas and questions arising from the pre-class content and activities.

2. Whilst there may be some barriers to adopting this approach, most (if not all) can be overcome.

3. The flipped classroom is very relevant to the University of Northampton at the moment as it is one of the models of teaching and learning which will work very well in the new Waterside campus. However, there’s no need to wait until we get to Waterside to try it out, as it’s something that will work well right now.

4. There is a lot of support available to staff wanting to try out the flipped classroom, and staff are encouraged to try out this approach to teaching and learning.

What the flipped classroom is

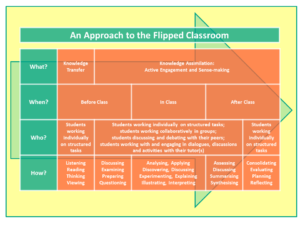

I was introduced to the idea of flipped learning in 2012 by the Harvard Professor Eric Mazur, when I attended his keynote speech2 at the annual conference of the Association for Learning Technology. The idea of the flipped classroom owes a great deal to the work of Mazur, whose ideas about peer instruction3 formulated at Harvard in the 1990s evolved into what we now term flipped learning. To use Mazur’s terminology, what happens in a traditional classroom is that class time is typically taken up with ‘knowledge transfer’, often a lecture, and students then complete tasks outside of class in order to process and understand the subject matter, which Mazur terms ‘knowledge assimilation’. What Mazur proposed is that the knowledge transfer stage should be covered prior to attending class, and that the class time could then be used to help students assimilate what they had read or watched prior to coming to class. The ‘flip’ is simply that knowledge transfer now happens outside class, and knowledge assimilation now happens in class.

“Mazur’s reinvention of the course drops the lecture model and deeply engages students in the learning/teaching endeavor. It starts from his view of education as a two-step process: information transfer, and then making sense of and assimilating that information. ‘In the standard approach, the emphasis in class is on the first, and the second is left to the student on his or her own, outside of the classroom,’ he says. ‘If you think about this rationally, you have to flip that, and put the first one outside the classroom, and the second inside. So I began to ask my students to read my lecture notes before class, and then tell me what questions they have [ordinarily, using the course’s website], and when we meet, we discuss those questions.'” 4

Putting the flipped classroom into practice

Obviously no classes at Northampton are taught only via lectures, and I suspect that very few (if any) lectures at Northampton are pure didactic monologues, but Mazur’s ideas could still be used to good effect to free up more class time to spend with students helping them to understand the material and the subject in more depth.

If this approach appeals to you, then an example of how you could put it into practice is by putting your lectures online, and using your class time to engage students in activities and tasks which will help them to fully understand the material which was covered in your lecture. The online lectures should be short, certainly no more than thirty minutes, but two fifteen minute lectures would be preferable. And supporting the video lectures will probably be some reading, a book chapter or journal article perhaps. Students may watch your lectures a few times in order to get the most from them, and students for whom English is not a first language may benefit greatly from the ability to watch and re-watch the lectures. You’ve now freed up an extra hour to spend with your students, so what’s the best way to use that hour?

Well, there are plenty of options here. If you’d prefer a more teacher-led session then one idea would be to ask your students to complete a pre-class test or survey in order to find out where the gaps in their understanding are. Perhaps you’d prefer to give them a test so that you can check their understanding yourself, or perhaps you’d prefer the students to determine for themselves what they did and did not understand, so you ask students to submit questions about the material. Their questions or their test results could then form the basis of a class session in which you discuss and answer the questions that the students submitted in the survey, or provide further clarification on the things they got wrong in the tests. This approach is often called ‘just in time teaching’ as you don’t really know what you need to cover in class until the test or survey results have been submitted, and this is often less than 24 hours before the class is due to start. If you’d prefer something more student-led then you could still use a pre-class test or survey, but this time you take the students questions (or develop your own questions based around the things they got wrong in the tests) and get the students to answer their questions themselves. This is the approach that Mazur uses, which he terms peer instruction.

“Mazur begins a class with a student-sourced question, then asks students to think the problem through and commit to an answer, which each records using a handheld device (smartphones work fine), and which a central computer statistically compiles, without displaying the overall tally. If between 30 and 70 percent of the class gets the correct answer (Mazur seeks controversy), he moves on to peer instruction. Students find a neighbor with a different answer and make a case for their own response. Each tries to convince the other. During the ensuing chaos, Mazur circulates through the room, eavesdropping on the conversations. He listens especially to incorrect reasoning, so ‘I can re-sensitize myself to the difficulties beginning learners face.’ After two or three minutes, the students vote again, and typically the percentage of correct answers dramatically improves. Then the cycle repeats.” 5

Other options could involve a blend of just in time teaching and peer instruction. These are not the only approaches though, and whilst there is no one correct way of doing things, it’s probably safe to say that an approach which sees the students actively engaged in class is likely to lead to them learning more than an approach in which the students are passive. A visual idea of how the flipped classroom could work in practice is given below:

Waterside – a flipped campus?

Can you flip a whole institution? Yes, you can. Clintondale High School in Michigan started flipping its classes in 2010, and now delivers all classes using the flipped model. They claim that this approach has led to dramatic reductions in both failure rates and discipline problems6. The University of Technology, Sydney, has developed a teaching and learning strategy which fits extremely well with flipped classrooms7, and has set up its own Flipped Learning Action Group to promote the use of this approach8. Does this mean that Waterside going to be a flipped campus? No, it doesn’t. Whilst we won’t have any lecture theatres, and while much of the teaching and learning will happen in smaller teaching spaces (twenty to forty students), a one-size-fits-all approach would not be the best option for the new campus. Nevertheless, what is encouraged for Waterside is what is encouraged at both Park and Avenue campuses here and now, which is participatory, student-led teaching and learning and the use of both class time and technology to engage students in active, exciting and transformative learning experiences.

Will students complain if I flip my classroom?

Possibly. Students may expect lectures and they may think that they learn from them. Students may also like lectures because they’re easy: not much is expected from attendees at lectures as they are “the teaching moment that most promotes passivity and discourages participation.”9 If you adopt a flipped learning approach then students will have to work harder both in class and before class. This is a good thing, and if you want to counter objections from students who want you to lecture you could refer them to bell hooks’ essay quoted above, ‘To Lecture or Not’10, where she tell us that “When we as a culture begin to be serious about teaching and learning, the large lecture will no longer occupy the prominent space that it has held for years.” You could also refer them to Graham Gibbs’ article, ‘Twenty terrible reasons for lecturing’11, in which he explains and provides evidence as to why lecturing does not “give students a rich and rewarding educational experience.”12 In addition, the recent National Union of Students’ publication ‘Radical Innovations in Teaching and Learning’ is worth referring students to as it asked universities to, amongst other things, consider what place the lecture has in “a modern, democratic university.”13

Support for flipping your classroom

What support is available to academics wanting to try out flipped learning? Well, an excellent place to start is with the Learning Designers and the Learning Technology Team. The Learning Designers will be able to explain more about flipped learning, and will be able to help you successfully plan and implement flipped classroom sessions. And the Learning Technology Team will be able to provide you with training and support regarding the technologies that you may want to use as part of your flipped classroom sessions.

To end, it’s worth pointing out that changing the way one teaches takes time, and without support from professional services staff, colleagues and managers, change is not likely to happen. Change, especially radical change, also needs failure to be acknowledged as a possible and legitimate outcome, as not every new technique that we try out will be a success. However, perhaps the flipped classroom offers a low-risk opportunity for change, as there is plenty of training and support available from the Learning Designers and the Learning Technology Team, and the evidence, which we will look at in a later posting, seems to suggest that this is an approach that works.

Contacts

Learning Designers: LD@northampton.ac.uk

Learning Technology Team: LearnTech@northampton.ac.uk

References

1. Parr, C. (2014) ‘Six trends in campus design: 5. Informal, flexible learning spaces.’ Times Higher Education Supplement. December 2014. [online]. Available from: http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/features/six-trends-in-campus-design/4/2017412.article

2. Mazur, E. (2012) ‘The scientific approach to teaching: research as a basis for course design.’ YouTube. [online]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aYiI2Hvg5LE

3. Lambert, C. (2012) ‘Twilight of the Lecture.’ Harvard Magazine. March/April 2012. [online]. Available from: http://harvardmagazine.com/2012/03/twilight-of-the-lecture

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. See: Clintondale High School (2012) Our Story. [online]. Available from: http://flippedhighschool.com/ourstory.php

7. UTS (2104) ‘Learning 2014 Strategy.’ YouTube. [online]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rL0eFmac7mA

8. UTS (2014) ‘Flipped Futures.’ UTS Newsroom. August 2014. [online]. Available from: http://newsroom.uts.edu.au/news/2014/08/flipped-futures

9. hooks, b. (2010) Teaching Critical Thinking: Practical Wisdom. Abingdon: Routledge. p.64.

10. Ibid. pp.63-68.

11. Gibbs, G. (1981) Twenty terrible reasons for lecturing. SCED Occasional Paper No. 8, Birmingham. 1981. [online]. Available from: http://shop.brookes.ac.uk/browse/extra_info.asp?compid=1&modid=1&deptid=47&catid=227&prodid=1174

12. Ibid.

13. NUS (2014) Radical Interventions in Teaching and Learning. [online]. Available from: http://www.nusconnect.org.uk/resources/open/highereducation/Radical-Interventions-in-Teaching-and-Learning/

Recent Posts

- Blackboard Upgrade – February 2026

- Blackboard Upgrade – January 2026

- Spotlight on Excellence: Bringing AI Conversations into Management Learning

- Blackboard Upgrade – December 2025

- Preparing for your Physiotherapy Apprenticeship Programme (PREP-PAP) by Fiona Barrett and Anna Smith

- Blackboard Upgrade – November 2025

- Fix Your Content Day 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – October 2025

- Blackboard Upgrade – September 2025

- The potential student benefits of staying engaged with learning and teaching material

Tags

ABL Practitioner Stories Academic Skills Accessibility Active Blended Learning (ABL) ADE AI Artificial Intelligence Assessment Design Assessment Tools Blackboard Blackboard Learn Blackboard Upgrade Blended Learning Blogs CAIeRO Collaborate Collaboration Distance Learning Feedback FHES Flipped Learning iNorthampton iPad Kaltura Learner Experience MALT Mobile Newsletter NILE NILE Ultra Outside the box Panopto Presentations Quality Reflection SHED Submitting and Grading Electronically (SaGE) Turnitin Ultra Ultra Upgrade Update Updates Video Waterside XerteArchives

Site Admin